Classified: The War on Backpage.com is now streaming on the video platform CiVL. It's a new 42-minute documentary film produced by Reason, directed by Paul Detrick, and reported by me. Classified features exclusive interviews with Backpage co-founder Michael Lacey as he awaited sentencing.

Lacey is now in prison, sentenced to five years. And his story bodes poorly for free speech online broadly, for sex workers who want safer working conditions, and for all sorts of tech companies.

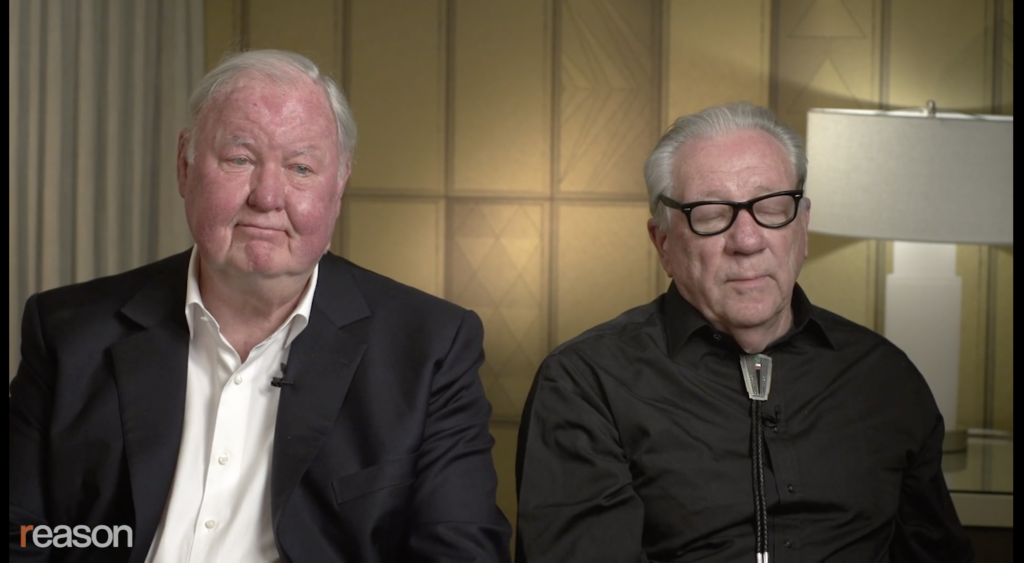

The first time I met Michael Lacey, he had just been grilled by members of the Senate. In the hallway after the hearing, reporters flanked him and James Larkin, Lacey's longtime friend and partner in the newspaper and later online classifieds business. They weren't answering questions. I waited until they had passed the crowd and went up and introduced myself. Lacey recognized my name from the years of Reason reporting I'd already done on Backpage. "Get in," he said as he, Larkin, and a small entourage of lawyers boarded an elevator. "What's next?" I asked them inside. Lacey looked at me deadpan: "A drink."

That was in 2017. Back then, anything involving Backpage commanded a lot of media attention. The site had been scapegoated by many in media and politics—including now-Vice President Kamala Harris—who seemed intent on stoking sex-trafficking panic, and held up by attorneys general and lawmakers as a reason for weakening free speech protections online.

From the beginning, the panic over "adult" ads online seemed to me misplaced. I knew from sex workers that such services were making their jobs easier and safer. And I knew from years of observing and reporting on how the government operates that there was something more going on here than simply misplaced concern by authorities.

Buzzwords like "sex trafficking" and "human trafficking" were being thrown around liberally by influential activist groups and celebrities, demanding that authorities do something to avoid allegations of indifference.

But it was more than that, too. The fact that so much of the sex industry had migrated online gave cover to people in power who sought more control of the internet broadly. They will use this, I thought (and wrote) then. And—oh boy—has that come to pass.

FOSTA (Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act) was the first significant weakening of the vital-for-free-speech-online provision known as Section 230. Lawmakers pushed through FOSTA with desperate warnings that it was needed to take down Backpage, which they had been framing for years as some sort of hotbed of child sex trafficking. Their tactics worked, and FOSTA passed, and the whole thing earned everyone involved a lot of media accolades.

But not only was their characterization of Backpage wrong, the idea that FOSTA was needed to "take down" Backpage was a lie, too. The Department of Justice seized the site and arrested Lacey, Larkin, and other former executives before FOSTA was actually signed into law.

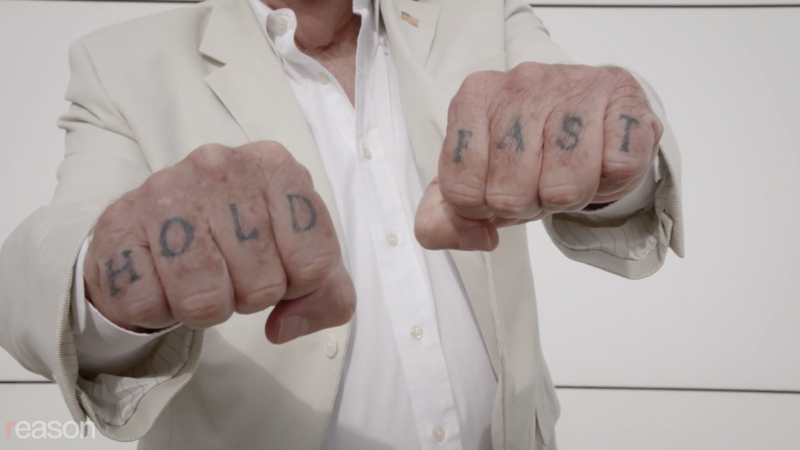

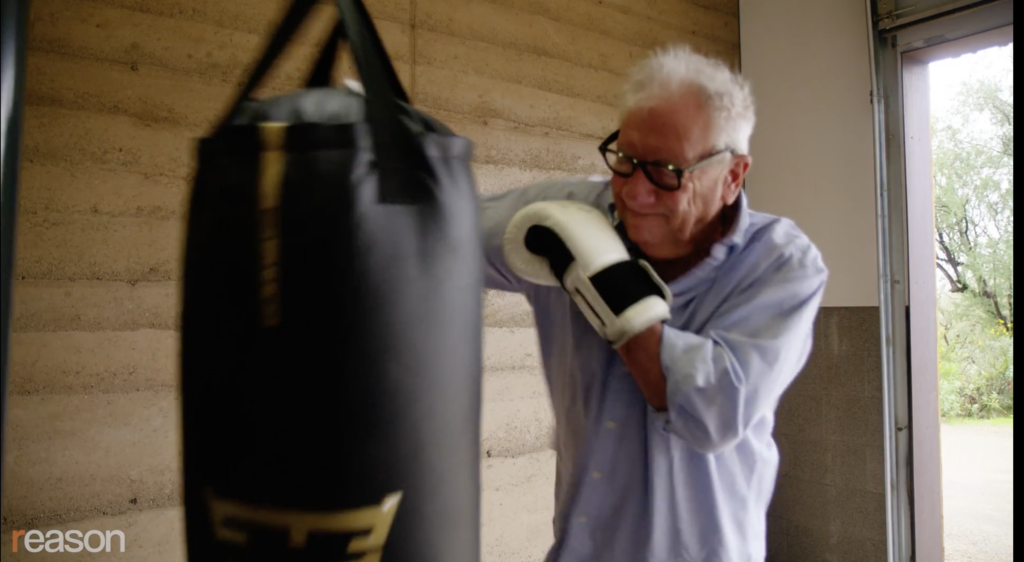

I spent some time in Phoenix during the week of 4th of July in 2018, a few months after the feds had raided Lacey's and Larkin's homes. They still weren't talking to much press, but they had invited me out to spend a few days interviewing them. I had no idea what to expect. I'm embarrassed to admit now that, at the time, I knew very little about their background—their very long and storied history in the alt-weekly newspaper world; their decades of fighting in court for their First Amendment rights; their decades of publishing pieces that took powerful people to task.

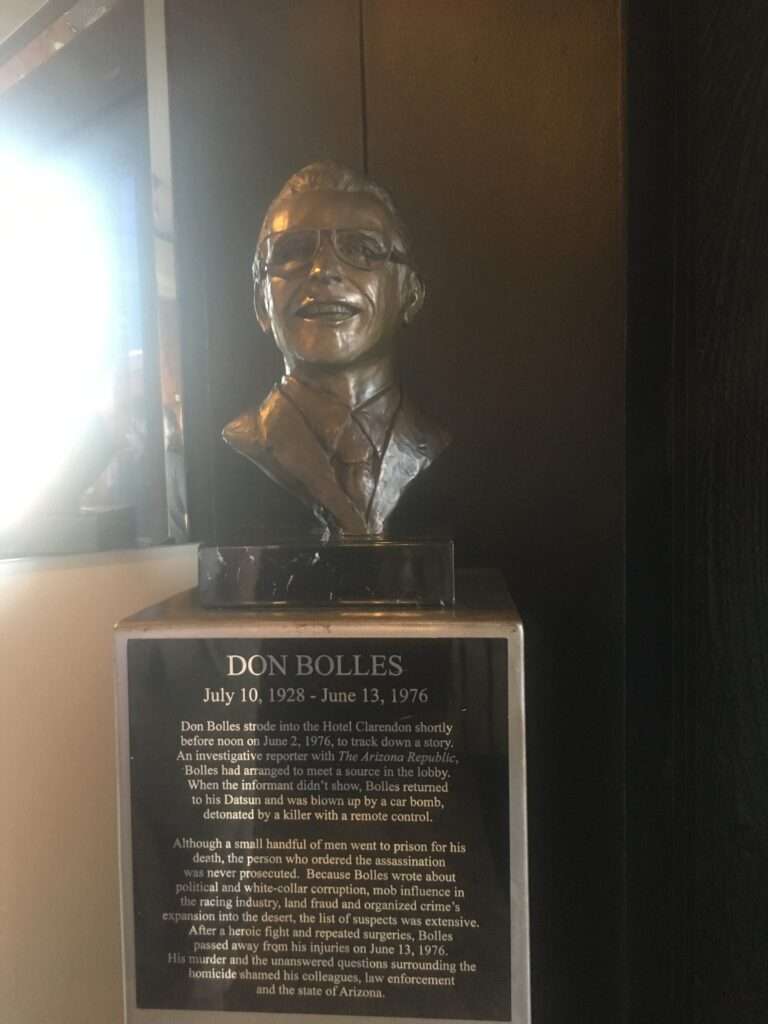

On that trip, they took me to a bar in Phoenix's Clarendon Hotel. Forty-eight years ago, Arizona Republic reporter Don Bolles had gone there to meet an alleged source and been blown up by dynamite placed in his car. A group of reporters had descended on Phoenix afterward to report on the story. "They came in to try to capture the environment where somebody thinks they could get away with killing a journalist," Lacey told me in 2018. Their pieces wound up "pointing a machine gun at all the players in Arizona." The Arizona Republic "refused to run it…And so we ran it," he said. It helped put their paper, the New Times, on the proverbial map. The Clarendon Hotel bar now features a bust of Bolles commissioned and donated by Lacey and Larkin. I think that's as good a glimpse as any into who these two are.

Since that 2018 trip to Phoenix, I interviewed them many times via phone and email, and once in person during a Reason gathering in Phoenix. But I did not get back out to Lacey's house until last March, when we started making Classified. Detrick, a videographer, and I spent two days out there interviewing and filming.

My youngest son—then about six months and refusing to take a bottle—had to accompany me and my husband along with him. They hung out in a guest room of Lacey's home while we filmed—the same room where federal agents had pulled his mother-in-law out of the shower at gunpoint six years prior.

Larkin wasn't there. He committed suicide about a week before their (second) trial began in summer 2023.

Talking to Lacey about the loss of his close friend and partner drove home even more the toll of this prosecution. "I literally screamed when I heard about [Jim's suicide] on the phone," Lacey told us. "He's gone, and he shouldn't be. He just shouldn't be." Larkin was "told repeatedly by every lawyer—not just most lawyers, but by every lawyer—that looked at Backpage that it was legal, okay? And here he was facing a really harsh road in prison. And…I think he just ran out of hope."

"The government has Jim Larkin's blood on its hands," Robert Corn-Revere, now a lawyer with the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), says in the film.

By the time of Larkin's death, the trial of the remaining defendants, and their sentencing this year, the story hardly made a media splash at all. Gone were the breathless reporting and the swarms of reporters. Silent were the politicians who had spent years demonizing Backpage.

It's pretty clear they were used—as scapegoats, as allegedly villainous foils to hero politicians, as a way to sell papers or get clicks. Now, everyone has moved on. But of course Lacey and Larkin and their families couldn't. The other defendants and their families couldn't. They are stuck dealing with the very tangible and profound aftermath of being made into public enemies, and of a prosecution that dragged on long past the point when politicians needed it for attention.

Now, those same politicians have moved on to demonizing other tech companies. Meta, TikTok, X, Snapchat, Discord…all the popular social media platforms have come under fire in recent years. Just like with Backpage, a lot of press has seemed all too happy to serve as conduits of the government's narrative—of evil tech companies who can only be stopped by brave officials willing to give themselves and others in power more control over the internet. And just like with Backpage, they've been selling this under the guise of protecting children, often accusing Facebook, Instagram, and so on of the exact sins that they pinned on Backpage years earlier. Meanwhile, sex workers are still reeling from the takedown of Backpage and the passage of FOSTA. And almost no one is claiming that any of it stopped sex trafficking or made anyone more safe.

That's one reason I'm passionate about this story—because it's so much bigger than just this story. It's about using the specter of suffering and safety to censor and surveil. It's about putting vulnerable people in more danger so powerful people can play the hero. But it's also about a few very specific people whose reputations have been ruined and lives upended over this. It's an abstract and monumental story that also has a very tangible, personal core.

I hope you'll watch our film. I've written so many words about all this over the years—and I'm a writer, so I clearly believe in the power of words. But there's a different kind of power in film, in watching and hearing Lacey talk about Larkin's death, the raid on his house, what he'll miss in prison. In seeing him as he approaches the courthouse on the day of sentencing. In hearing former sex worker Kaytlin Bailey talk about how the loss of online advertising has been so bad for the people this was supposed to help; hearing Corn-Revere talk about the brutal tactics the prosecution used; hearing Techdirt Editor-in-Chief Mike Masnick warn about where this is all going. "It was easy for them to do it with Larkin and Lacey," says Masnick in the film. "It would be easy for them to do it to Zuckerberg or whoever else they want to go after."

You might not have much sympathy for Zuckerberg, or any Big Tech CEOs. But going after tech CEOs doesn't just affect tech CEOs. As sex workers who lost access to Backpage and other online platforms can tell you, going after tech heads trickles down, and we all wind up less free.

Classified: The War on Backpage.com will be streaming exclusively on CiVL for the next few weeks, after which it will also appear on YouTube. You can watch it now for free if you sign up for a CiVL account.

More Sex & Tech News

• More than a dozen states are suing TikTok in the name of protecting children.

• A group of sites promising to use artificial intelligence to "nudify" photos are actually a malware scheme run by a Russian cybercrime group, according to cybersecurity researchers.

• The "Hands Off My Porn" campaign aims to sound a warning about Project 2025 and Republican plans to ban pornography.

• A federal judge says Google's Play Store for Android apps must allow users to download third-party app stores.

• "The Georgia Supreme Court on Monday restored the state's six-week abortion ban, halting a judge's ruling a week ago that the six-week ban is unconstitutional and abortions could continue past six weeks," reports CBS News. "The six-week ban will remain in place while Georgia's highest court considers the state's appeal."

• The Department of Justice issued recommendations for how Google should be punished after it was found guilty of an antitrust law violation. "The filing in the U.S. District Court in Washington hinted that the justice department was looking at breaking up the company as one option to 'prevent and restrain' Google's monopolistic grip on the U.S. markets for general search services and general search text," notes UPI.

Today's Image

The post Watch Now: <em>Classified: The War on Backpage.com</em> appeared first on Reason.com.