Faced with the prospect of sending Russian troops into subterranean combat, Vladimir Putin demurred. “There is no need to climb into these catacombs and crawl underground,” he told his defense minister on April 21, 2022, ordering him to cancel a planned storming of a steel plant in the besieged Ukrainian port city of Mariupol.

While Putin’s back-up plan – to form a seal around trapped Ukrainian forces and wait it out – is no less brutal and there are reports that Russians may still have mounted an offensive on the site, Putin’s hesitancy to send his forces into a sprawling network of tunnels under the complex hints at a truth in warfare: Tunnels can be an effective tool in resisting an oppressor.

Indeed since the war began in February, reports have emerged of Ukrainian defenders using underground tunnel networks in efforts to deny Russian invaders control of major cities, as well as to provide sanctuary for civilians.

As an expert in military history and theory, I know there is sound thinking behind using tunnels as both a defensive and offensive tactic. Such networks allow small units to move undetected by aerial sensors and emerge in unexpected locations to launch surprise attacks and then essentially disappear. For an invader who does not possess a thorough map of the subterranean passages, this can present a nightmare scenario, leading to massive personnel losses, plummeting morale and an inability to finish the conquest of their urban objective – all factors that may have factored in Putin’s decision not to send troops underground in Mariupol.

A history of military tunneling from ancient roots

The use of tunnels and underground chambers in times of conflict is nothing new.

The use of tunnels has been a common aspect of warfare for millennia. Ancient besieging forces used tunneling operations as a means to weaken otherwise well-fortified positions. This typically required engineers to construct long passages under walls or other obstacles. Collapsing the tunnel weakened the fortification. If well-timed, an assault conducted in the immediate aftermath of the breach might lead to a successful storming of the defended position.

One of the earliest examples of this technique is depicted on Assyrian carvings that are thousands of years old. While some attackers climb ladders to storm the walls of an Egyptian city, others can be seen digging at the foundations of the walls.

Roman armies relied heavily upon sophisticated engineering techniques such as putting arches into the tunnels they built during sieges. Roman defenders also perfected the art of digging counter-tunnels to intercept those used by attackers before they presented a threat. Upon penetrating an enemy tunnel, they flooded it with caustic smoke to drive out the enemy or launched a surprise attack upon unsuspecting miners.

The success of tunneling under fortifications led European engineers in the Middle Ages to design ways to thwart the tactic. They built castles on bedrock foundations, making any attempt to dig beneath them much slower, and surrounded walls with moats so that tunnels would need to be far deeper.

Although tunneling remained an important aspect of sieges through the 13th century, it was eventually replaced by the introduction of gunpowder artillery – which proved a more effective way to breach fortifications.

However, by the mid-19th century, advances in mining and tunnel construction led to a resurgence in subterranean approaches to warfare.

During the Crimean War in the 1850s, British and French attackers attempted to tunnel under Russian fortifications at the Battle of Sevastopol. Ten years later, Ulysses S. Grant authorized an attempt to tunnel under Confederate defenses at the siege of Petersburg, Virginia. In both cases, large caches of gunpowder were placed in chambers created by tunneling under key positions and detonated in coordination with an infantry assault.

Tunneling in the age of airpower

With warfare increasingly relying on aircraft in the 20th century, military strategists again turned to tunnels – undetectable from the skies and protected from falling bombs.

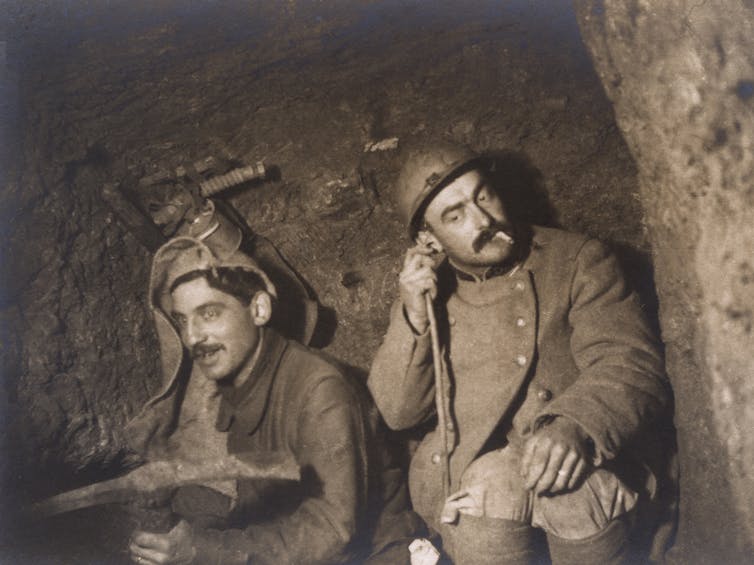

In World War I, tunneling was attempted as a means to launch surprise attacks on the Western Front, potentially bypassing the other side’s system of trenches and remaining undetected by aerial observers. In particular, the Ypres salient in war-ravaged Belgium was the site of hundreds of tunnels dug by British and German miners, and the horrifying stories of combat under the earth provide one of the most terrifying vignettes of that awful war.

During World War II, Japanese troops in occupied areas in the Pacific constructed extensive tunnel networks to make their forces virtually immune to aerial attack and naval bombardment from Allied forces. During amphibious assaults in places such as the Philippines and Iwo Jima, American and Allied forces had to contend with a warren of Japanese tunnel networks. Eventually they resorted to using high explosives to collapse tunnel entrances, trapping thousands of Japanese troops inside.

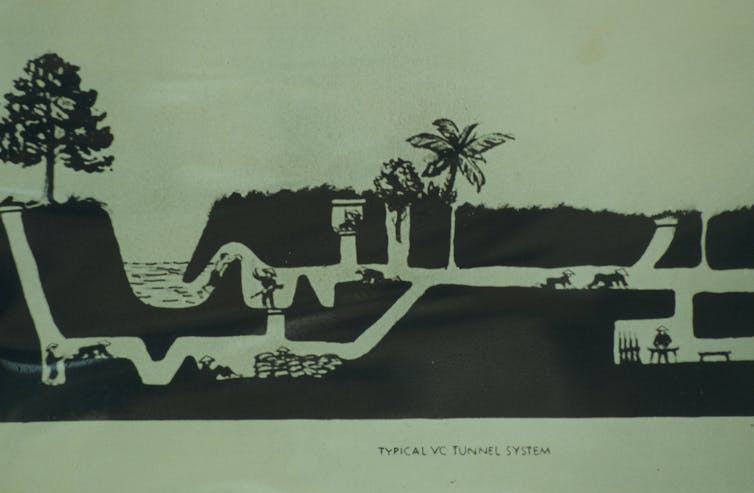

The Viet Cong tunnel networks, particularly in the vicinity of Saigon, were an essential part of their guerrilla strategy and remain a popular tourist stop today. Some of the tunnels were large enough to house hospital and barracks facilities and strong enough to withstand anything short of nuclear bombardment.

The tunnels not only protected Vietnamese fighters from overwhelming American airpower, they also facilitated hit-and-run style attacks. Specialized “tunnel rats,” American soldiers who ventured into the tunnels armed only with a knife and pistol, became adept at navigating the tunnel networks. But they could not be trained in sufficient numbers to negate the value of the tunnel systems.

Tunnels for terrorism

In the 21st century, tunnels have been used to facilitate the activities of terror organizations. During the American-led invasion of Afghanistan, military operatives soon discovered that al-Qaida had fortified a series of tunnel networks connecting naturally occurring caves in the Tora Bora region.

Not only did they hide the movement of troops and supplies, they proved impervious to virtually every weapon in the U.S.-led coalition’s arsenal. The complexes included air filtration systems to prevent chemical contamination, as well as massive storerooms and sophisticated communications gear allowing al-Qaida leadership to maintain control over their followers.

And tunneling activity in and around Gaza continues to provide a tool for Hamas to get fighters into Israeli territory, while at the same time allowing Palestinians to circumvent Israel’s blockade of Gaza’s borders.

Soviet tunnels and Ukraine

Many of the tunnels being utilized today in Ukrainian efforts to defend the country were built in the Cold War-era, when the United States routinely engaged in overflights of Soviet territory.

To counteract the significant air and satellite advantage held by the United States and NATO, the Soviet military dug underground passages under major population centers.

These subterranean systems offered a certain amount of shelter for the civilian population in the event of a nuclear attack and allowed for the movement of military forces unobserved by the ever-present eyes in the sky.

These same tunnels serve to connect much of the industrial infrastructure in Mariupol today – and have become a major asset for the outnumbered Ukrainian forces.

Other Ukrainian cities have similar systems, some dating back centuries. For example, Odesa, another key Black Sea port, has a catacomb network stretching over 2,500 kilometers. It began as part of a limestone mining effort – and to date, there is no documented map of the full extent of the tunnels.

In the event of a Russian assault on Odesa, the local knowledge of the underground passages might prove to be an extremely valuable asset for the defenders. The fact that more than 1,000 entrances to the catacombs have been identified should surely give Russian attackers pause before commencing any attack upon the city – just as the tunnels under a steelworks in Mariupol forced Putin to rethinks plans to storm the facility.

Paul J. Springer is a Senior Fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute. His comments represent his own opinion and do not reflect the official policy of the United States Government, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. Air Force.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.