Cases of tularemia — a rare and sometimes fatal infectious disease that is also known commonly as “rabbit fever” — have risen in the US in recent years.

Between 2011 and 2022, there’s been a 56 percent increase in the annual average incidence of tularemia infections compared with previous years from 2001 to 2010, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Health officials said that more than 2,400 cases were reported during the more recent time frame in a report published Monday in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Cases were the highest among children between the ages of five and nine years old, older men, and American Indian or Alaska Natives.

Furthermore, the majority of the cases reported by 47 states came from just four. Around half were reported in Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma.

This jump is largely a result of increased reporting of probable cases, the agency noted.

“These findings might reflect an actual increase in human infection or improved case detection amid changes in commercially available laboratory tests during this period,” the report’s authors said.

Although case numbers remain low, there was an average of 205 each year between 2011 and 2022.

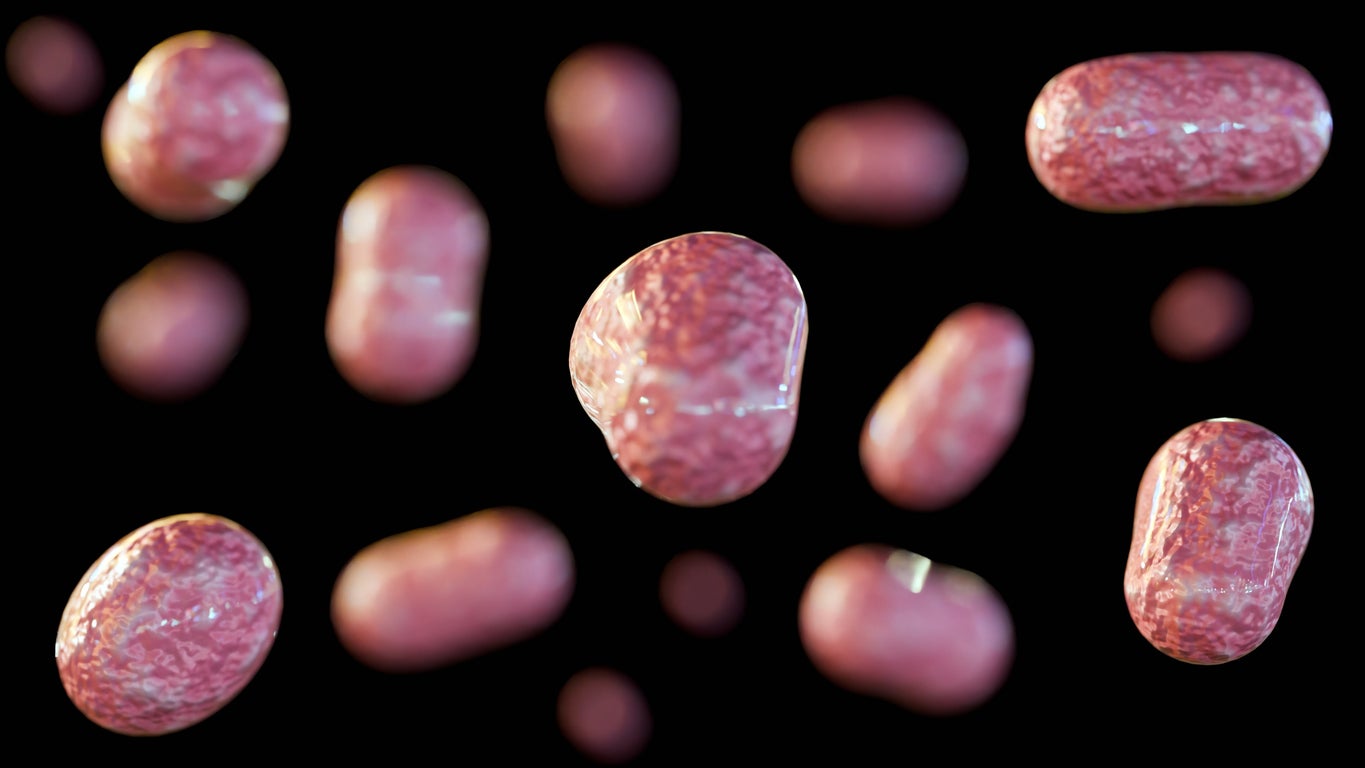

Caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis, tularemia can be spread to humans by infected animals, like rabbits and prairie dogs, as well as through tick or deer fly bites, by drinking contaminated water and by inhaling contaminated dust.

The bacteria that causes infection has been designated a Tier 1 Select Agent, or the highest risk category, based on its potential for use as a bioweapon.

While symptoms vary, they can include, skin ulcers, pneumonia, and swollen lymph nodes, that are accompanied by fever.

Signs of illness are apparent after three to five days, and the majority of patients were reported to have their symptoms start between May and September.

Vaccination for tularemia is not generally available in the U.S. The illness is treatable with antibiotics, and the case fatality rate is typically less than 2 percent — although it can be as high as 24 percent.

The report called for action to reduce the number of cases.

“Reducing tularemia incidence will require tailored prevention education; mitigating morbidity and mortality will require health care provider education, particularly among providers serving tribal populations, regarding early and accurate diagnosis and treatment,” it said.