India is facing a water and food crisis, exacerbated by extreme climate cycles such as the current heatwave during which temperatures well above 40℃ have been commonplace. With 1.4 billion people to feed, and such heatwaves set to become more common, the country clearly needs more sustainable agriculture.

In Punjab, a northwestern “breadbasket” state of 27 million people, policymakers are now seriously considering crop diversity, a marked shift away from a previous emphasis on fields of solely wheat or rice. The problem is those crops use lots of precious groundwater, which is fast being depleted. State data shows that groundwater is being overdrawn by 14 billion cubic metres per year. In 1984, less than half of the state’s “administrative blocks” were over exploited, today it is nearing 80%.

For now, Punjab is focused on increasing the use of crops such as maize, pulses, oilseeds, cotton, and even poplar trees which grow quickly and are used for wood or paper. But some young farmers – less averse to behavioural change and more tolerant of risk than older generations – are instead turning to a crop with an ancient history.

Back to millets

Millets are a group of cereals that come in a number of species and are known as a superfood for their nutrient-rich composition and high content of starch and proteins. They offer health benefits especially for people suffering with coronary disease and diabetes, and millet consumption manages body sugar levels, promotes detoxification and helps in digestion. Porridge, cookies, pancakes and breads made from millet are consumed in many parts of the world.

Importantly, millets offer a great alternative to rice as they don’t need much water, are pest resilient, have a very long shelf life and are profitable. Research finds millets to be heat tolerant making them a sensible crop choice in a changing climate.

Millets have always been grown in Punjab, even if they were never dominant. Archaeological evidence reveals they were used in the early days of agriculture, long before even the appearance of the cities of the Indus civilisation. Millets also helped feed the region’s population (and their cattle) during extended periods of aridity and variable rainfall that affected the subcontinent a little over 4,000 years ago.

Despite this deep history, millet cropping in India declined in recent decades. For instance, bajra (Pearl millet) was grown on 217,000 hectares in Punjab in the 1950s, but was reduced to a mere 500 hectares in 2020. But cultivation is now picking up again as the state’s rice farmers grow millets.

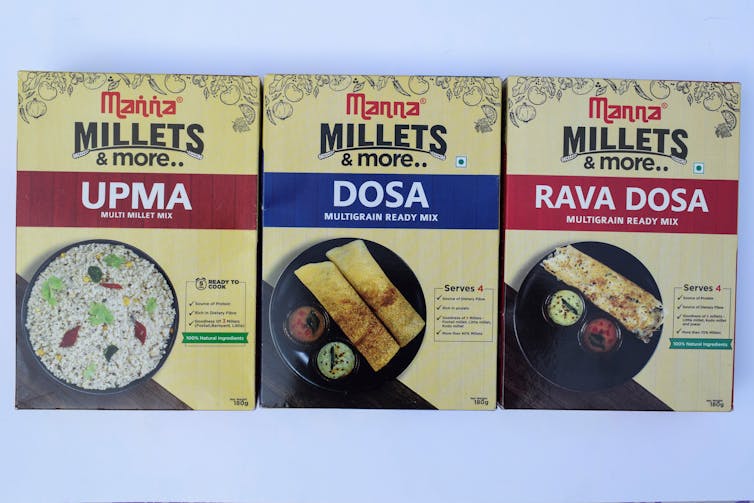

Millets such as ragi, bajra and guar are now being cultivated as a supplementary crop in scattered and pocket-sized areas by more entrepreneurial farmers. This practice is being influenced by active flow of information and knowledge about climate change, shifting agricultural policy environment and evolving consumer markets which have increased demand. Besides selling these crops as raw millets, farmers are collectively selling processed, packaged and branded consumer millet products. Though millet is easy to grow, its profitability is ultimately dependant on these market forces.

Part of a sustainable solution

Though the economic returns from millet are high, the yields – production per unit of land – are about six times lower than that of rice. Millet is therefore not a universal solution, but it should be part of a package of crops that can be grown more sustainably and that are more adaptable to variations in climate. After all, the current level of rice cultivation is not sustainable either, as groundwater is running low. Importantly, millet can be grown on land that is not (or no longer) suitable for growing rice.

It is clear that Punjab must diversify away from rice and embrace alternate crops. Though this prerogative is with the farmers, the government must also encourage and facilitate diversification through subsidies and other policy supports. Punjab benefits from a young population with a strong agricultural legacy. The time has come to tap into this legacy, diversify its crops, and help make Indian agriculture more sustainable.

Shruti Bhogal is working as a researcher under the project TIGR2ESS, that is a Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) Project. Shruti Bhogal is affiliated with Centers for International Projects Trust (CIPT), New Delhi, where she works as a Post Doctoral Research Associate. CIPT is a Not-for-profit organisation that was established by the Columbia Water Center, Columbia University in 2008.

Adam S. Green receives funding from the United Kingdom's Global Challenges Research Fund.

Cameron Andrew Petrie has received funding from the UKRI Global Challenges Reseach Fund for FP4 of the TIGR2ESS project: Transforming India's Green Revolution by Research and Empowerment for Sustainable food Supplies.

Sandeep Dixit receives funding from TIGR2ESS.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.