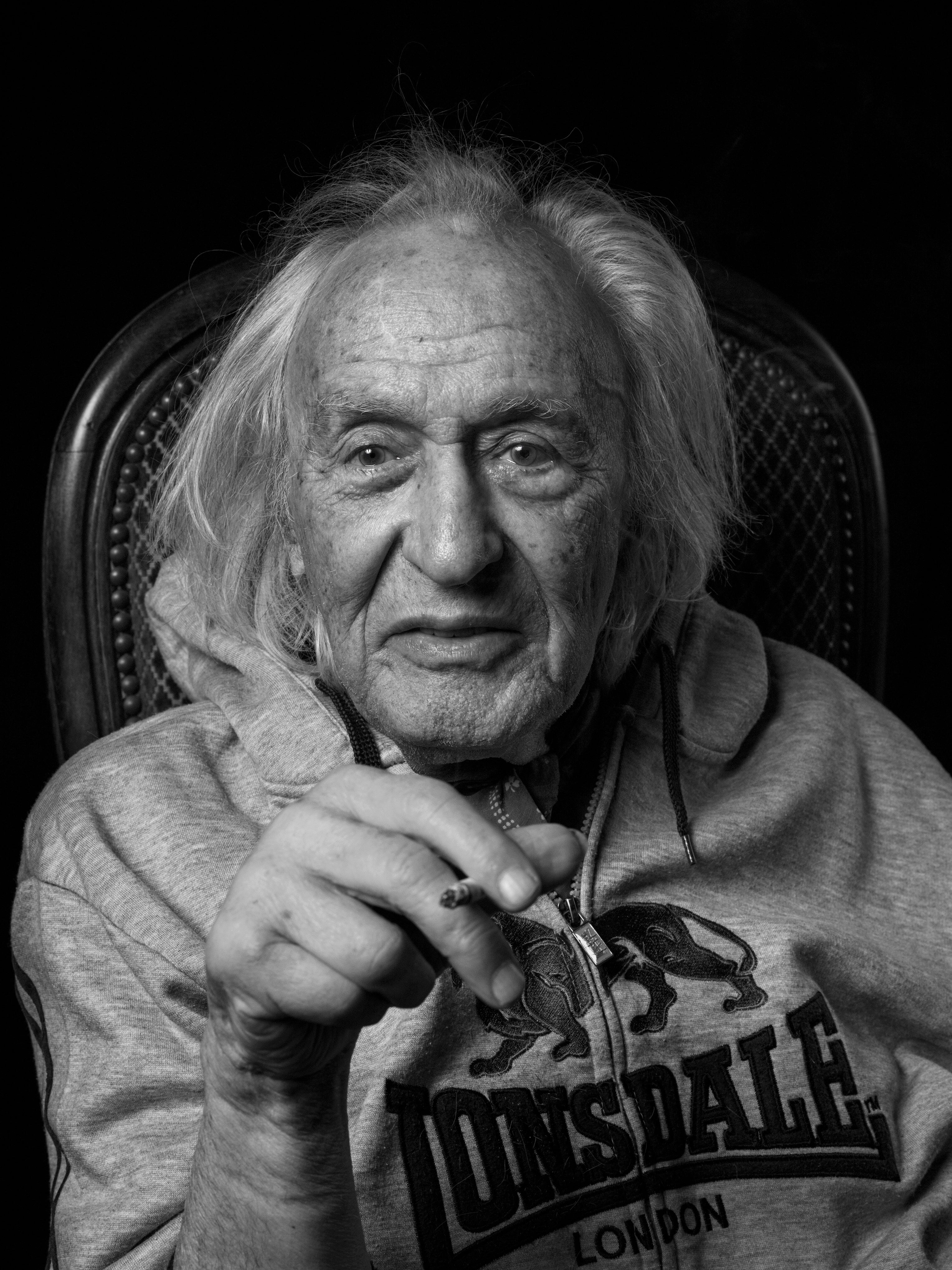

William Klein, an American expatriate photographer whose often frenetic and sometimes blurred images of urban street life and modern fashion were wildly innovative while conveying the pointed social criticism of a self-declared outsider, has died aged 96.

From his earliest years, Klein said, he was attuned to seeing the world as a perpetual foreigner. He grew up in Depression-era Manhattan, a Jewish boy in a largely Irish neighbourhood, where he endured poverty and antisemitic bullying. Self-reliance and a quick eye for his surroundings were his means of survival – and so was art. At 12, he began spending weekends roaming the Museum of Modern Art, where his own work would one day be displayed.

After military service, he settled in France in the late 1940s to study painting. But he was soon captivated by photography when he realised how playing with exposures could form, with endless possibilities, a new kind of abstract art. The vibrant blurs he created were a revelation, he said, of the mood he felt swirling around him and his vision of the world in general: its grit, its vibrancy, its gorgeousness, its grotesqueries.

He proudly distanced himself from any school or method as he came to prominence in the post-war years, favouring raw instinct over any established technique.

“I came from the outside; the rules of photography didn’t interest me,” he once said. “There were things you could do with a camera that you couldn’t do with any other medium – grain, contrast, blur, cockeyed framing, eliminating or exaggerating grey tones and so on. I thought it would be good to show what’s possible, to say that this is as valid a way of using the camera as conventional approaches.”

Vogue’s celebrated art director, Alexander Liberman, who said he saw in Klein “a wonderful iconoclastic talent”, put him under contract to the fashion magazine from 1955 to 1965. Klein offered radically original images that incorporated blur, flash lighting, high-contrast printing and the odd perspectives allowed by wide-angle and telephoto lenses.

“They were probably the most unpopular fashion photographs Vogue ever published,” Klein told The Observer.

While living on Vogue’s allowance, he embarked on a personal project: a series of photographs taken on the streets of New York with the same techniques he was applying to fashion. In Klein’s lens, the streets revealed a messy modern world alive with action and opportunity, but also teeming with hostility.

Rejected by Vogue and by American book publishers, the pictures were published in an idiosyncratic tabloid-style book. Its full title, Life Is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels, was a collage of tabloid headlines.

New York, as the book became commonly known, was published in France in 1956 but not in America. Like Robert Frank’s landmark cross-country photographic volume, The Americans (1959), Klein's book cast a gimlet eye on the myth of the American Dream at the height of the Cold War. Klein called it “my diatribe against America”.

Although many American art and photography critics disapproved of Klein’s style – one accused him of “cheap sensational photography” – the book proved enduringly influential. In 1992, Vicki Goldberg, a photography historian and critic, described Klein in The New York Times as a born rulebreaker who “played a major role in codifying a new outlook” in visual arts.

He often used a wide-angle lens to include faces on the periphery of the frame or a telephoto lens to condense near and far figures, and he photographed his subjects before they were fully aware of his presence. He used the developing process to create high-contrast and other posterish effects, and he often cropped the results.

Klein’s most reproduced image from the book, known as “Gun 1”, shows a young boy with a clenched, angry expression pointing a gun at the photographer, just inches from the lens. A smaller angelic-looking boy seems to attempt to restrain his companion by putting a hand on his sleeve. The boys were playacting, Klein explained, but nonetheless seemed to embody the emotional drama of urban life.

New York was a multicultural tour de force, featuring many Black and immigrant faces. The telephoto shot known as “4 Heads, New York” features in one frame, according to Klein, an Italian police officer, a Hispanic man, a Jewish mother and an African American woman wearing a beret.

The book’s design was wildly experimental. Some photographs bleed off the edges of the page; others are grouped in grids. The volume included a separately bound 16-page booklet containing captions for the pictures and a reproduction of a Mad magazine cover, ersatz adverts for spaghetti and bras, and other ephemera. This apparent critique of rampant commercialism predated the Pop Art of Andy Warhol.

Klein characterised his work as “pseudo-ethnographic, parodic, Dada”, the last referring to a playfully absurdist art movement of the early 20th century. He went on to photograph other cities – Rome, Moscow, Tokyo – while also pursuing filmmaking, training his lens on people who, like him, had challenged the cultural mainstream.

His subjects included boxer Muhammad Ali, Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver and rock-and-roll pioneer Little Richard. In addition to his documentaries, Klein created French-language features, including the fashion-world spoof Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966) and the comedy Mr Freedom (1968), about a superhero who uses his powers to bolster American corporate and military imperialism.

Despite his prodigious output over more than 70 years, Klein never achieved the recognition in his native country that peers such as Robert Frank and Richard Avedon enjoyed. The explanation lay partly in his absence. But his independent streak also helped to undercut his relationships with editors, art directors and curators. It would be decades before his work received major exhibitions in the US.

Klein said he remained a “foreigner” even in his adopted country, always the outside observer primed to see complexities under the surface charm. His 2002 book Paris + Klein – showing Rubenesque women in a Turkish bath, African-born protesters demanding their rights, Chinese New Year celebrations – spurned the romanticised vision of the City of Lights.

William Klein was born in Manhattan on 19 April 1926. His father was a tailor who owned a clothing store but lost it in the 1929 stock market crash; his mother was a homemaker.

A precocious student, he graduated from high school at 14 and enrolled at the City College of New York. He left in 1946 to enlist in the army. While stationed in Allied-occupied Germany, he became a cartoonist for the military newspaper Stars and Stripes, and, by his account, he won his first camera, a professional-grade Rolleiflex, in a poker game on the base.

Upon his discharge in 1948, he moved to Paris to attend the Sorbonne and studied under painter Fernand Léger. A few years later, abstract photographs he took for the architectural magazine Domus were seen by Liberman, who brought him back to New York to work for Vogue.

Klein married Jeanne Florin (also known as Janine) after spotting her on the Left Bank in his first week in Paris. She worked briefly as a model and later managed her husband’s schedule. She died in 2005. Survivors include a son, Pierre Klein, and a sister.

William Klein, photographer, born 19 April 1926, died 10 September 2022

© The Washington Post