Menopause is one of nature’s greatest evolutionary mysteries. From a survivalist standpoint, there’s no advantage to a species for an individual to continue living beyond reproductive years. Menopausal individuals theoretically use up precious resources that could go to more reproducing members or their young. (Yikes, brutal.) In fact, most other mammals can reproduce their entire lifespan. Elephants can reproduce into their 60s, and baleen whales into their 90s.

Humans are part of a privileged few (including some toothed whales) that cease menstruation and carry on living.

Now, chimpanzees are now part of that elite group.

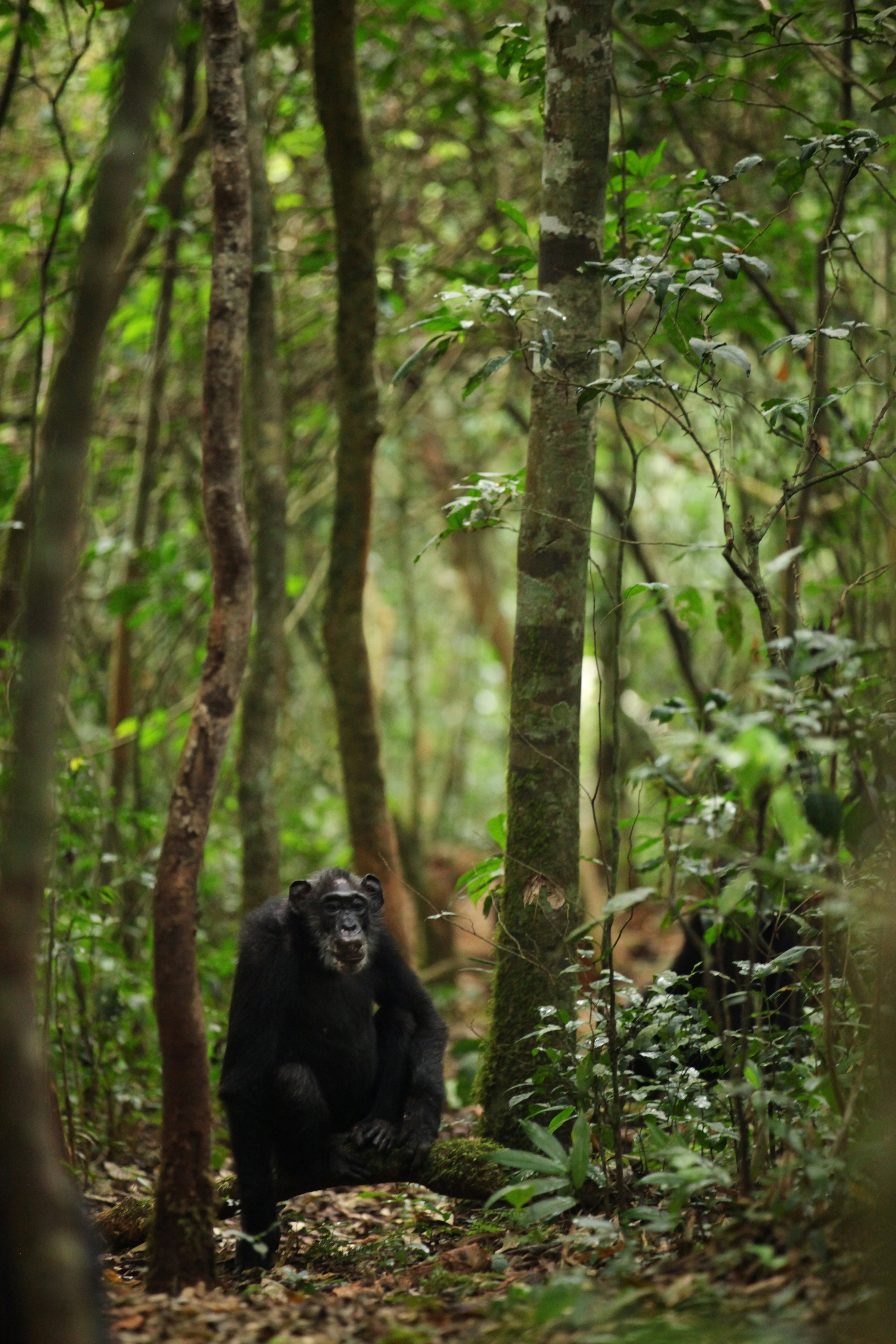

While captive chimpanzees have been observed to live past menopause, researchers in the U.S. and Germany have, for the first time, seen the phenomenon in wild Ngogo chimps of Kibale National Park in western Uganda. Today, the team published a study in the journal Science demonstrating what portion of a chimp’s life is likely to be lived post-reproductive years, as well as a surprising finding that further links us with these animals.

Seen in the wild

While researchers have for years found that female chimps in captivity live past reproductive age, the identification of the same phenomenon in wild chimps helps provide confirmation that this trait helps them survive in the wild.

“The wild-captive distinction is really key,” says first author Brian Wood, professor of evolutionary anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles. Species develop particular traits because those traits help them survive in their environment. In captivity, where all their needs are met, and there are no predators, evolution has no need. “Captivity doesn't give you that because it's a completely novel, artificial context that doesn't allow you to make any inferences about the adaptive function or its consequences,” Wood tells Inverse.

Further, it’s hard to understand the evolution of a trait like menopause because “it sort of flies in the face of intuition,” Kevin Langergraber, senior study author and professor of behavioral and molecular ecology at Arizona State University, tells Inverse. “Chimps are joining a very small club of animals where you've got substantial post-reproductive lifespans in the wild.”

This looks familiar

The team studied available fertility data on 185 Ngogo chimps that occurred between 1995 and 2016. They calculated a statistic called the post-reproductive representation (PrR). PrR quantifies the portion of a chimp’s life that is post-fertility, Wood says. To calculate PrR, they needed two values: the age at which a female’s reproductive “career” begins (when 5 percent of lifetime fertility has begun, beginning with giving birth) and when it ends (when 95 percent of births have been completed).

“One of the take-home lessons from our study is gaining more of an appreciation for how variable those [PrR] rates are in chimps,” Wood says.

Another component of the study is demonstrating that reproductive cessation actually occurred because of the same reason menopause happens in humans. Wood says when he and his team presented their preliminary findings at a conference in 2017, one of his “academic heroes,” Melissa Emery Thompson, an evolutionary anthropology professor at the University of New Mexico and later a co-author of the study, suggested that this change in reproductive function could be caused by a number of things that should be ruled out, such as sexually transmitted diseases.

This inspired Woods’ team to return to the data and analyze urine samples from 66 of these chimps for hormone fluctuations. Thompson’s lab processed these samples, and indeed, the hormone changes mirrored those that occur in human menopause. Follicle-stimulating hormone, for example, shot through the roof as estrogen levels declined. “It was just all the more wonderful when those results came back, and we could see them plotted by age, just like you see with humans undergoing menopause,” Wood says.

Reconstructing evolutionary history

We still don’t know why any species evolved to hit menopause. For humans, one hypothesis proposes that those who live beyond reproductive years can help raise grandchildren, improving their fitness into adulthood. However, “Chimps don’t do a lot of grandmothering,” Langergraber says. Other theories exist, but none fully explain or account for the benefits of menopause in all species that seem to experience it.

Wood says it’s significant that chimps — the animal we’re more closely related to than any other great ape — are predisposed to experience menopause. Understanding that is “important for reconstructing the evolutionary history of the trait.”

Unraveling menopause could bring us closer to finding where chimps and humans diverged in the lineage. “This lends plausibility to the idea that the last common ancestor that we had with chimps could have been already predisposed to having this lengthened post-reproductive life stage,” he says. “That's one part of this larger effort to try to really understand what this is about in human evolutionary history.”