The Bank of England has raised interest rates 11 times since December 2021 but, while this may boost bank profits, it is less likely to boost many people’s bank balances.

Alongside the sharp spike in interest rates over the past year, many big names in the UK banking business have been reporting bumper 2022 profits. NatWest made £5.1 billion in 2022 before tax, up 33% and the highest since the 2008 global financial crisis. Fellow high street bank Lloyds made nearly £7 billion before taxes in 2022.

Much like the energy companies that have experienced huge increases in profits as gas and electricity prices soared over the past year, the same is now happening at the UK’s large retail banks as Bank of England interest rates have done the same.

These increases have little to do with CEO performance (although top executives took home significant pay packets for 2022) or increases in efficiency within these banks. But they have everything to do with how retail banks make their money and the domination of the market by several key players.

Retail banking income has two main sources: interest income from lending or fee income from non-interest business (and sometimes a little trading income). Retail banks also earn interest on the billions they hold in reserves with the Bank of England – this income has of course increased recently as the central bank has hiked its main rate.

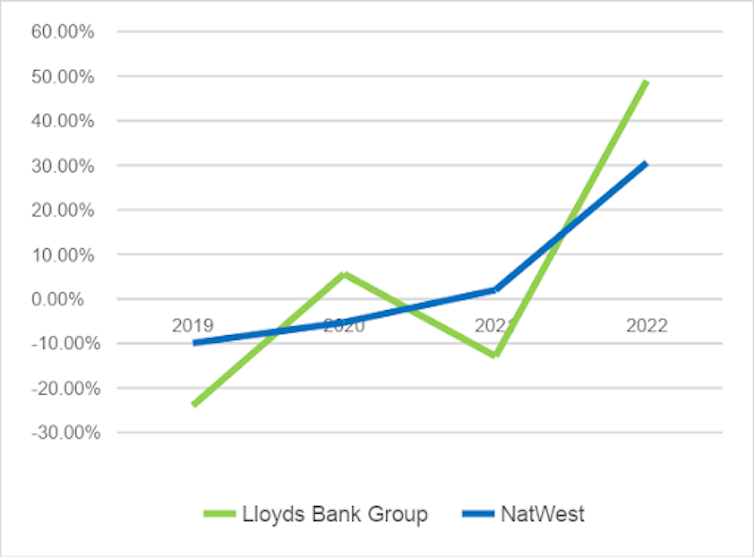

In the past 12 months there has been quite a steep rise in interest income, in particular net interest income. This is the amount banks pay out in interest (to savers, for example) versus the amount they make in interest from lending. So, for example, during 2022 NatWest Banking Group achieved a 30.6% increase in net interest income and Lloyds Banking Group an increase of nearly 50%.

Growth in net interest income

There is some history behind these recent profits. In the mid-1980s, the “big bang” began the deregulation of banking in the UK. This led to a change in the traditional banking business model towards riskier activities.

Rather than making money from getting and holding on to deposits and loans (a strategy known as “originate and hold”) banks started to package up their loans and sell them on to further boost their profits (“originate to distribute”). The resulting rise in this business and the focus on non-interest income such as fees for non-traditional business ultimately led to the largest financial crisis the world has ever seen.

A new era in banking

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, some retail banks have retrenched into older-style banking. NatWest, for example, now makes over 60% of its revenue from deposits and lending, for Lloyds this figure is about 70%. But others, including HSBC and Barclays, have continued to make over 60% of their total revenue from non-interest income sources, according to their latest financial reports.

The latter strategy makes sense in the very low interest rate environment that the UK was in up until 2022. When the central bank base rate is low, there is little money to be made from lending and holding deposits so banks can make more money from non-interest income. But when interest rates start to rise, the big winners are those focused on the deposit and lending markets.

This is because even though the Bank of England raises the bank rate to influence other interest rates, large retail banks get to choose when they feed these rate changes on to savers and borrowers.

Loans make up 70% or more of total assets at some high street banks. This alone helps to boost revenues when rates rise. Many banks also charge a much higher rate on lending than they pay out for retail deposits and have been criticised in recent months for failing to pass on savings rate increases as quickly as they’ve boosted mortgage costs.

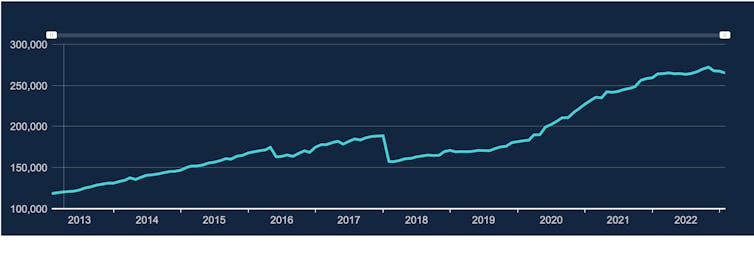

This means that, at the same time banks are seeing increases in their interest income from loans (and their reserves at the Bank of England), the amount they are paying out in interest to depositors in some accounts can remain the same for a longer period – sometimes at 0%. Shockingly, the Bank of England estimates that UK households have a massive £265 billion sitting in non-interest-bearing deposits, up from £118 billion a decade ago.

UK household savings not earning interest (£ millions)

Even then, research suggests retail banks tend to be much slower at increasing deposit rates than lending rates. Policymakers seem to have noticed this as the CEOs from four major UK retail banks – Barclays, NatWest, Lloyds and HSBC – were called to appear at a Treasury Committee hearing in February 2023 to discuss rapid increases in loan and mortgage rates versus limited rate rises for savers and depositors, among other issues.

“Customer choice” was cited as the main reason for the difference. All of the CEOs pointed out recent increases in rates on some savings products. However, research shows savers often don’t switch into these higher-paying accounts, people simply do not manage their deposits in such a dynamic way.

Since large retail banks dominate the deposit and lending market in the UK, they are unlikely to change this aspect of their operations on their own. Some kind of regulation could help to force banks to pass on rate rises more quickly, of course. Introducing a windfall tax could also help.

But both of these solutions seem unlikely to happen in light of the government’s recent banking reforms and the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (although this was not linked to net interest income). The fear of another banking collapse, alongside the new reforms, will only reinforce the perceived importance of bank profits and shareholders over consumers – even during a cost of living crisis.

Robert Webb does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.