People around the world eat too much sugar. When the body is unable to process sugar effectively, leading to excess glucose in the blood, this can result in diabetes. According to the World Health Organization, diabetes became the ninth leading cause of death in 2019.

Humans are not the only mammals that love sugar. Fruit bats do, too, eating up to twice their body weight in sugary fruit a day. However, unlike humans, fruit bats thrive on a sugar-rich diet. They can lower their blood sugar faster than bats that rely on insects as their main food source.

We are a team of biologists and bioengineers. Determining how fruit bats evolved to specialize on a high-sugar diet sent us on a quest to approach diabetes therapy from an unusual angle – one that sent us all the way to Lamanai, Belize, for the Belize Bat-a-thon, an annual gathering where researchers collect and study bats.

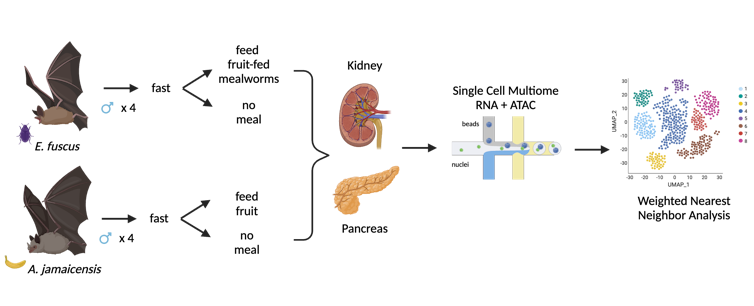

In our newly published research in Nature Communications, we and colleagues Seungbyn Baek and Martin Hemberg used a technology that analyzes the DNA of individual cells to compare the unique metabolic instructions encoded in the genome of the Jamaican fruit bat, Artibeus jamaicensis, with those in the genome of the insect-eating big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus.

Approximately 2% of DNA is composed of genes, which are segments of DNA that contain the instructions cells use to create certain traits, such as a longer tongue in fruit bats. The other 98% are segments of DNA that regulate genes and determine the presence and absence of the traits they encode.

To understand how fruit bats evolved to consume so much sugar, we wanted to identify the genetic and cellular differences between bats that eat fruit and bats that eat insects. Specifically, we looked at the genes, regulatory DNA and cell types in two significant organs involved in metabolic disease: the pancreas and the kidney.

The pancreas regulates blood sugar and appetite by secreting hormones like insulin, which lowers your blood sugar, and glucagon, which raises your blood sugar. We found Jamaican fruit bats have more insulin-producing and glucagon-producing cells than big brown bats, along with regulatory DNA that primes fruit bat pancreatic cells to initiate production of insulin and glucagon. Together these two hormones work to keep blood sugar levels balanced even when the fruit bats are eating large amounts of sugar.

The kidney filters metabolic waste from the blood, maintains water and salt balance and regulates blood pressure. Fruit bat kidneys need to be equipped to remove from their bloodstreams the large amounts of water that come from fruit while retaining the low amounts of salt in fruit. We found Jamaican fruit bats have adjusted the compositions of their kidney cells in accordance with their diet, reducing the number of urine-concentrating cells so their urine is more diluted with water compared with big brown bats.

Why it matters

Diabetes is one of the most expensive chronic conditions in the world. The U.S. spent US$412.9 billion in 2022 on direct medical costs and indirect costs related to diabetes.

Most approaches to developing new treatments for diabetes are based on traditional laboratory animals such as mice because they are easy to reproduce and study in a lab. But outside the lab, there exist mammals like fruit bats that have actually evolved to withstand high sugar loads. Figuring out how these mammals deal with high sugar loads can help researchers identify new approaches to treat diabetes.

By applying new cell characterization technologies on these nonmodel organisms, or organisms researchers don’t usually use for research in the lab, we and a growing body of researchers show that nature could be leveraged to develop novel treatment approaches for disease.

What still isn’t known

While our study revealed many potential therapeutic targets for diabetes, more research needs to be done to demonstrate whether our fruit bat DNA sequences can help understand, manage or cure diabetes in humans.

Some of our fruit bat findings may be unrelated to metabolism or are specific only to Jamaican fruit bats. There are close to 200 species of fruit bats. Studying more bats will help researchers clarify which fruit bat DNA sequences are relevant for diabetes treatment.

Our study also focused only on bat pancreases and kidneys. Analyzing other organs involved in metabolism, such as the liver and small intestine, will help researchers more comprehensively understand fruit bat metabolism and design appropriate treatments.

What’s next

Our team is now testing the regulatory DNA sequences that allow fruit bats to eat so much sugar and checking whether we can use them to better regulate how people respond to glucose.

We are doing this by swapping the regulatory DNA sequences in mice with those of fruit bats and testing their effects on how well these mice manage their glucose levels.

The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

Wei Gordon receives funding from NSF.

Nadav Ahituv is a cofounder and on the scientific advisory board of Regel Therapeutics and also received funding from BioMarin Pharmaceutical Incorporate. Funding for this research was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute grant R01HG012396.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.