When you picture Jupiter, you probably see a planet with orange and reddish bands and the famous Great Red Spot staring at you like a giant eye.

But did you know those famous bands are ever-changing in size, color and location? Every four to five years, Jupiter changes its stripes, and ever since Galileo Galilei observed them in the 17th century, scientists have wondered why.

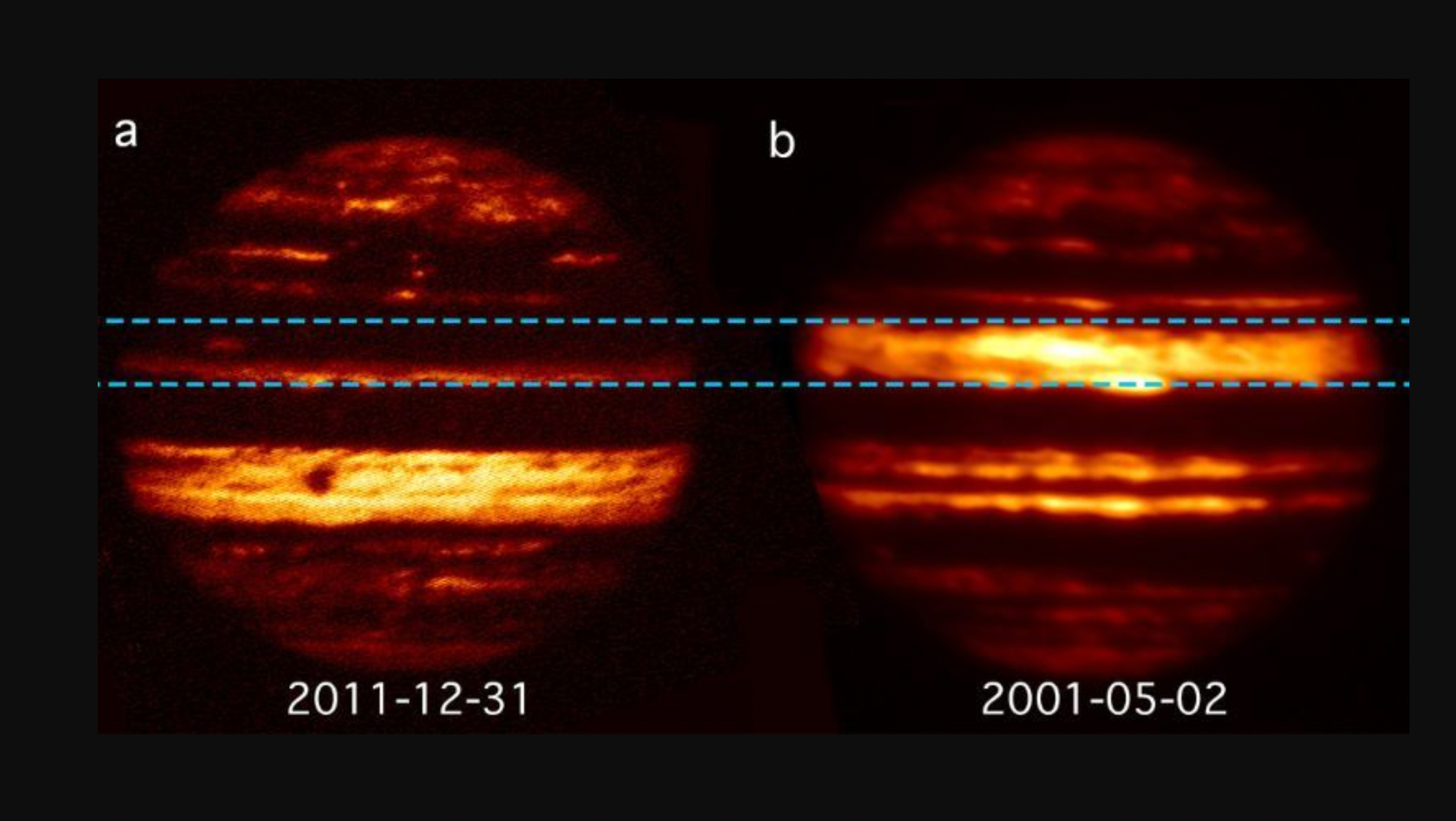

What we do know is that each band, consisting of clouds of ammonia and water in a hydrogen and helium atmosphere, corresponds to strong winds blowing east or west. Scientists have also linked the bands, which reach more than 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) deep into Jupiter's atmosphere, to changes in infrared variations within the planet. But a team of researchers has just discovered another important clue, and it all comes down to Jupiter's magnetic field.

Related: Jupiter, the solar system's largest planet (photos)

Using data from NASA's Jupiter-orbiting Juno spacecraft, the team correlated the variations in the gas giant's bands to changes in its magnetic field.

"It is possible to get wavelike motions in a planetary magnetic field, which are called torsional oscillations. The exciting thing is that, when we calculated the periods of these torsional oscillations, they corresponded to the periods that you see in the infrared radiation on Jupiter," study co-author Chris Jones, a professor in the School of Maths at the University of Leeds in England, said in a statement.

As it goes in the science world, this discovery produces even more mysteries.

"There remain uncertainties and questions, particularly how exactly the torsional oscillation produces the observed infrared variation, which likely reflects the complex dynamics and cloud/aerosol reactions. Those need more research," study lead author Kumiko Hori, formerly of the University of Leeds and currently of Kobe University in Japan, said in the same statement.

"Nonetheless, I hope our paper could also open a window to probe the hidden deep interior of Jupiter, just like seismology does for the Earth and helioseismology does for the sun," Hori said.

The team's research was published on May 18 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Follow Stefanie Waldek on Twitter @StefanieWaldek. Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.