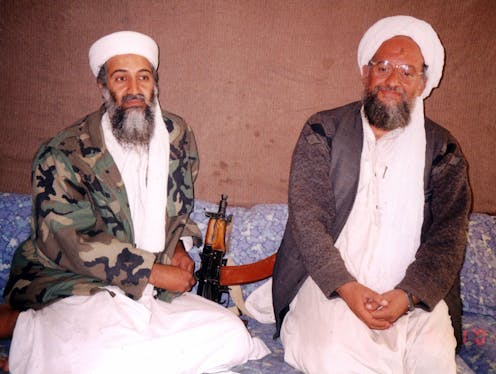

Ayman al-Zawahri, leader of al-Qaida and a plotter of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, has been killed in a drone strike in the Afghan city of Kabul, according to the U.S. government.

Al-Zawahri was the the successor to Osama bin Laden and his death marked “one more measure of closure” to the families of those killed in the 2001 atrocities, U.S. President Joe Biden said during televised remarks on Aug. 1, 2022.

The operation came almost a year after American troops exited Afghanistan after decades of fighting there. The Conversation asked Daniel Milton, a terrorism expert at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and Haroro J. Ingram and Andrew Mines, research fellows at the George Washington University’s Program on Extremism, to explain the significance of the strike on al-Zawahri and what it says about U.S. counterterrorism efforts in Afghanistan under the Taliban.

Who was Ayman al-Zawahri?

Ayman al-Zawahri was an Egyptian-born jihadist who became al-Qaida’s top leader in 2011 after his predecessor, Osama bin Laden, was killed by a U.S. operation. Al-Zawahri’s ascent followed years in which al-Qaida’s leadership had been devastated by U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan. Bin Laden had himself been struggling in the years leading up to his death to exert control and unity across al-Qaida’s global network of affiliates.

Al-Zawahri succeeded bin Laden despite a mixed reputation. While he had a long history of involvement in the jihadist struggle, he was viewed by many observers and even jihadists as a languid orator without formal religious credentials or battlefield reputation.

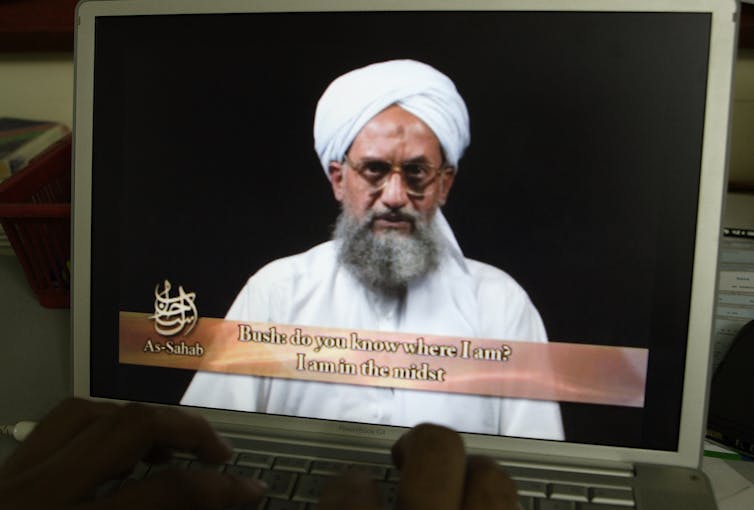

Lacking the charisma of his predecessor, al-Zawahri’s image as a leader was not helped by a tendency to embark on long, meandering and often outdated speeches. Al-Zawahri also struggled to shake rumors that he was a prison informer while detained in Egypt and, as author and journalist Lawrence Wright detailed, acted as a wedge between the young bin Laden and his mentor, Abdullah Azzam.

Al-Zawahri’s influence further waned during a series of popular uprisings known as the Arab Spring swept across North Africa and the Middle East, when it seemed that al-Qaida had been sidelined and unable to effectively exploit the outbreak of war in Syria and Iraq. To analysts and supporters alike, al-Zawahiri appeared symbolic of an al-Qaida that was outdated and rapidly being eclipsed by other groups that it had once helped onto the global stage, most notably the Islamic State.

But with the collapse of the Islamic State group’s caliphate in 2019, the return to power in Afghanistan of al-Qaida ally the Taliban and the persistence of al-Qaida affiliates especially in Africa, some experts argue that al-Zawahri guided al-Qaida through its most challenging period and that the group remains a potent threat. Indeed, one senior Biden administration official told the Associated Press that at the time of his death, al-Zawahri continued to provide “strategic direction” and was considered a dangerous figure.

Where does his death leave al-Qaida?

Killing or capturing top terrorist leaders has been a key counterterrorism tool for decades. Such operations remove terrorist leaders from the battlefield and force succession struggles that disrupt group cohesion and can expose security vulnerabilities. Unlike the Islamic State, which has clear leadership succession practices that it has showcased four times since the 2006 death of its founder Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, al-Qaida’s are less clear. Al-Zawahri’s successor will only be the movement’s third leader since forming in 1988.

The top contender is another Egyptian. A former colonel in the Egyptian army and, like al-Zawahri, a member of the al-Qaida affiliate Egyptian Islamic Jihad, Saif al-Adel is connected to the 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya that launched al-Qaida as a global jihadist threat. His reputation as an explosives expert and military strategist has won him strong standing within the al-Qaida movement. A number of other possibilities are behind al-Adel, with a recent U.N. Security Council report identifying several possible successors.

Either way, we’d argue that al-Qaida is at a crossroads. If al-Zawahri’s successor is broadly recognized as legitimate by both al-Qaida’s core and its affiliates, it could help to stabilize the movement. But any ambiguity surrounding al-Qaida’s succession plan could see the new leader’s authority challenged, which in turn could fracture the movement further.

Evidence suggests al-Qaida’s presence as a global movement will survive al-Zawahri’s death, just as it did bin Laden’s. The network has seen a number of recent successes. Longtime allies the Taliban successfully took control of Afghanistan with help from al-Qaida in the Indian Subcontinent – an affiliate which is now expanding its operations in Pakistan and India. Meanwhile, affiliates across the African continent – from Mali and the Lake Chad region to Somalia – remain a threat, with some expanding beyond their traditional areas of operation.

Other affiliates, like the group’s Yemen-based al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula, remain loyal to the core and, according to the U.N. monitoring team, are keen to revive overseas attacks against the U.S. and its allies.

Now, al-Zawahri’s successor will be looking to retain the allegiance of al-Qaida’s affiliates as it strives to remain a potent threat.

What does this tell us about US operations in Afghanistan under the Taliban?

The American withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 prompted questions over whether the U.S. could keep pressure on al-Qaida, ISIS-K and other militants in the country.

U.S. officials explained that an “over-the-horizon” strategy – launching surgical strikes and special operations raids from outside any given state – would allow the U.S. to deal with problems that emerged, such as terrorist attacks and the resurgence of groups.

But many experts disagreed. And when an errant U.S. drone strike killed seven children, a U.S.-employed humanitarian worker and other civilians last fall, that strategy came under sharp scrutiny.

But for those who doubted whether the U.S. still had the desire to go after key terrorists in Afghanistan, the killing of al-Zawahri gives a clear answer. This strike reportedly involved long-term surveillance of Zawahri and his family and robust discussion within the U.S. government before receiving presidential approval. Biden claims it was carried out without civilian casualties.

At the same time, it took the U.S. 11 months to strike its first high-value target in Afghanistan under the Taliban. This contrasts with the hundreds of airstrikes executed in the years before the U.S. withdrawal.

The strike occurred in a Kabul neighborhood populated by senior Taliban figures. The safehouse itself belonged to a senior aide to Sirajuddin Haqqani, a terrorist wanted by the U.S. and a top Taliban leader.

Aiding and abetting al-Zawahri was a violation of the Doha agreement, under which the Taliban agreed “not to cooperate with groups or individuals threatening the security of the United States and its allies.” The circumstances of the strike suggest that if the U.S. wants to do effective over-the-horizon operations in Afghanistan, it cannot count on the Taliban for support.

The strike on al-Zawahri also tells us little about whether the U.S. strategy post-pullout can contain other jihadist groups in the region like ISIS-K, which is vehemently opposed to the Taliban and expanding in Afghanistan.

Indeed, we believe that if more jihadists perceive the Taliban to be too weak to protect the top leaders of al-Qaida and its affiliates, while at the same time unable to govern Afghanistan without U.S. aid, many may consider ISIS-K to be the best choice.

These and other dynamics speak to the many challenges of pursuing an over-the-horizon counterterrorism in Afghanistan today, ones that are unlikely to be solved by occasional high-profile drone strikes and assassinations.

The views expressed by Dr. Milton are his own and not of the U.S. Military Academy, the Department of the Army, or any other agency of the U.S. Government

Andrew Mines and Haroro J. Ingram do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.