Monkeypox is continuing to spread across the globe with cases now reported in the US, Canada, Australia, Mexico, Argentina, Morocco, Spain, Portugal, France, Germany, Italy and Sweden.

In Britain, the total number of confirmed infections has now risen to 2,208 as of 21 July 2022. Of these, 2,115 are in England.

“The monkeypox outbreak in the UK continues to grow, with over a thousand cases now confirmed nationwide,” said Dr Sophia Makki, incident director at the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA).

“We expect cases to continue to rise further in the coming days and weeks.

“If you are attending large events over the summer or having sex with new partners, be alert to any monkeypox symptoms so you can get tested rapidly and help avoid passing the infection on.”

The UKHSA is currently investigating possible connections between the infected British patients and has noted that four diagnosed together on Monday 16 May were all gay or bisexual men, warning that that could indicate the virus is being sexually transmitted among that community.

Mateo Prochazka, an infectious disease epidemiologist at UKHSA who is leading the agency’s investigation, said that shared circumstance was “highly suggestive of spread in sexual networks”.

Dr Susan Hopkins, chief medical adviser to the UKHSA, said in a statement: “We are particularly urging men who are gay and bisexual to be aware of any unusual rashes or lesions and to contact a sexual health service without delay.”

British healthcare workers are being offered smallpox vaccines as a means of protection. No specific monkeypox vaccine currently exists but the smallpox variation is thought to be 85 per cent effective against it.

Meanwhile, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has a team of experts meeting regularly to monitor the growing crisis.

So what precisely is it and how much danger does it pose to the public?

Where did monkeypox originate?

The WHO has traced the sickness to the tropical rainforests of Central and West Africa and defines it as a viral zoonotic disease – meaning it can be transmitted from animals to humans – with the first case recorded in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970.

While it would have initially been transmitted to humans by contact with the blood or bodily fluids of contaminated primates, or via intermediary rodents such as tree squirrels and Gambian rats, it is much more likely to be caught from fellow humans.

That said, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warns there is a “theoretical risk” the disease could be capable of airborne tranmission.

In the 2017 outbreak that took place in Nigeria, the largest seen so far, 172 suspected cases of monkeypox were identified and 61 confirmed cases were reported across the country.

What are the symptoms?

A relatively mild viral infection, the disease has a six-to-16 day incubation period and sees patients first suffer fever, headaches, swellings, back pain, aching muscles and a general listlessness in its opening stages.

Once that passes and the fever breaks, the sufferer will experience a skin eruption, in which a rash spreads across the face, followed by the rest of the body, most commonly the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.

The blemishes evolve from lesions into crusted blisters, which can then take three weeks to heal and disappear.

According to the CDC: “The main difference between symptoms of smallpox and monkeypox is that monkeypox causes lymph nodes to swell (lymphadenopathy) while smallpox does not.”

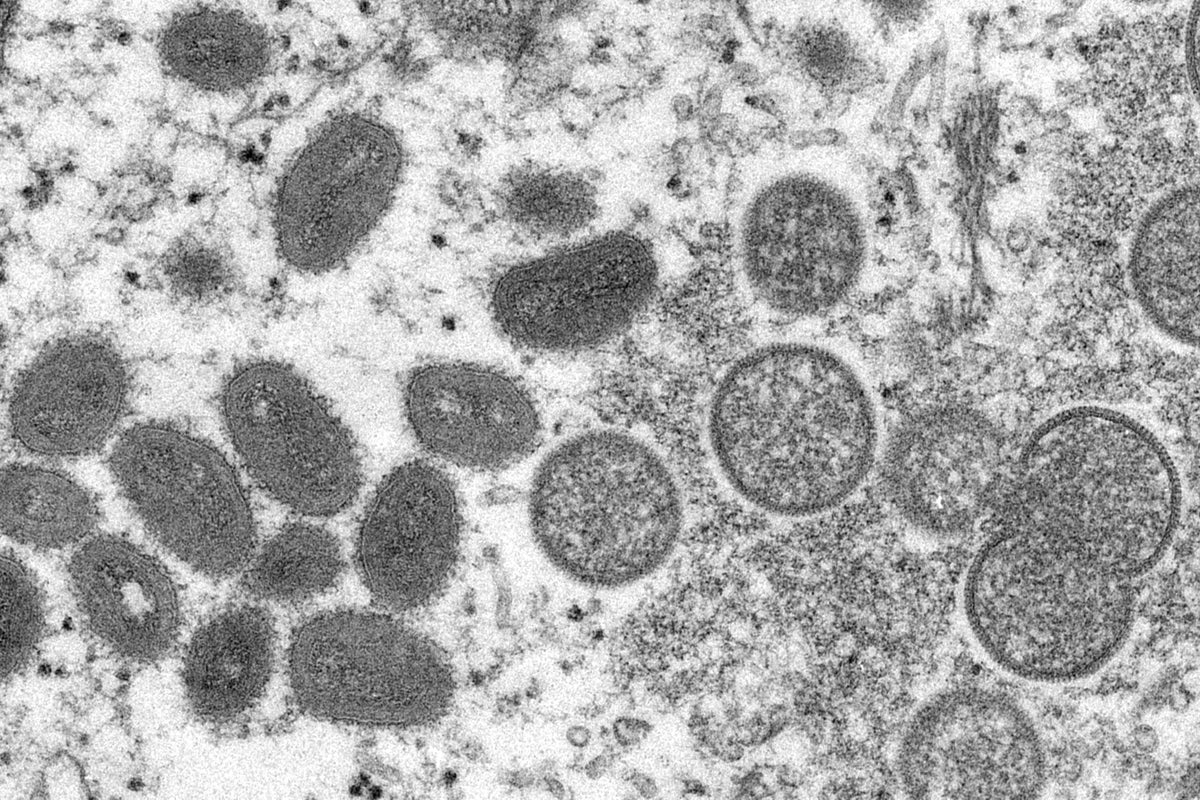

The virus can be difficult to diagnose without the aid of laboratory analysis because of its superficial similarity to other afflictions that result in a rash, such as chickenpox, measles, scabies and syphilis.

How dangerous is it?

Dr Colin Brown, director of clinical and emerging infections at the UKHSA, has said monkeypox “does not spread easily between people and the overall risk to the general public is very low”.

Professor Jimmy Whitworth of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine has agreed with that assessment but stressed that while monkeypox is “usually mild... it is a sensible precaution that those people who may have come into contact with these recent cases are being traced and followed up”.

Fatalities have been recorded, particularly among the young, although the WHO puts the mortality rate for the disease at just one in ten.

Dr Michael Head, a senior research fellow in global health at the University of Southampton, admits that there are “currently gaps in our knowledge” but added that it “would be very unusual to see anything more than a handful of cases in any outbreak” and stressed that “we won’t be seeing Covid-style levels of transmission”.