The 100th anniversary of Marcel Proust’s death gives us an opportunity to remember his masterwork, In Search of Lost Time, a sort of French-style Divine Comedy first released in 1913. Much like the way Dante’s 13th-century work forms a neat summary of Medieval wisdom, In Search of Lost Time attempts to cover every facet of human knowledge acquired at the dawn of the 20th century.

It discusses aesthetics with archetypal artists (through characters such as Vinteuil, the composer; Elstir, the painter; and Bergotte, the writer), addresses medicine by touching on Freudian psychology, and broaches the art of battle, right at the cusp of World War I. Proust refers liberally to contemporary technological developments, including the telephone, which enables him to communicate with the ghost of his beloved grandmother, the train that leaves the Saint-Lazare station, and the wondrous airplane that appears to him as a god would to an Ancient Greek. He is familiar with the theory of evolution, stating “‘Selection'… seemed to me as incompatible… as it would be if preceded by the adjective 'Natural’.”

Ultimately, Proust runs through the many decisive scientific breakthroughs of his time. The early 20th century witnessed two revolutions in physics that shattered our established worldview: relativity, which disputed the absolute nature of time, and quantum mechanics, whose indeterminacy challenged reality itself.

Here are some of the passages where Proust refers to momentous advances in his work.

Humble beginnings in school day memories

In Purgatory, Canto 15, Dante alludes to the first law of optics, which theorises light reflection and will be formalised by Descartes in the 17th century. Proust invokes the second law, which concerns refraction, in a tender description of his relationship with his grandmother:

“[My] thoughts were continued in her without having to undergo any deflection, since they passed from my mind into hers without change of atmosphere or of personality.”

He also recalls other lessons from high school:

“[To] a physicist the space occupied by the tiniest ball of pith is explained by the harmony of action, the conflict or equilibrium, of laws of attraction or repulsion which govern far greater worlds.”

These passages brim with the charm of bygone schooldays, when Proust would have carried out experiments such as electrifying an ebonite rod with a cat’s pelt. Any physicist would easily spot the Doppler effect in this sentence:

“There was also a new whistle… that was itself exactly like the scream of a tramway, and, as it was not carried out of earshot by its own velocity, one thought of a single car, not endowed with motion, or broken down, immobilised, screaming at short intervals like a dying animal.”

Doleron/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.

“It encountered in her the electric shock of a contrary will which violently repulsed it; I could see the sparks flash from her eyes.”

However, this last statement would have been disputed by Charles-Augustin Coulomb, whose law states that unlike charges attract while like charges repel each other!

Proust’s X-ray vision

Coming into more modern physics, Proust writes on several instances about ultraviolet and infrared rays. He also mentions X-rays, which were discovered in 1895 by Wilhelm Röntgen. To quote his character, Françoise:

“Madame knows everything; Madame is worse than the X-rays.”

In the book, this phrase is uttered at a time in the writer’s early youth, even though Proust was actually 24 when Röntgen made his discovery. It might therefore be suggested that the servant character of Françoise had some sort of prophetic gift. Later in the book, he returns to this physical phenomenon:

“[This] strange print which seems to us to have so little resemblance to ourselves bears sometimes the same stamp of truth, scarcely flattering, indeed, but profound and useful, as a photograph taken by X-rays.”

Proust even appears to claim to have a see-through vision of reality:

“It was all very well for me to go out to dinner. I did not see the guests because when I thought I was observing them I was radiographing them.”

He does not shy away, either, from the subject of radioactivity. Thought to have therapeutic properties, radioactive anti-ageing creams were popularly purchased at the time. In this regard, Proust ventures a bold metaphor when marvelling at the longevity of his character, Madame Swann, who represents:

“a more miraculous challenge to the laws of chronology than the conservation of radium to those of nature.”

Madame Curie’s prized radium is an unstable element that decays over a period of 1,600 years. A long time, indeed, but other elements last even longer, given that stable isotopes have an infinite lifespan.

Proust on time

Naturally, time plays a fundamental role in Proust’s seminal work. The concept is present in both the opening line of the book (“For a long time I used to go to bed early”) and the closing one (“… in Time”).

Proust’s era saw a total overhaul in our perception of time. Of course, today, we still do not know what time really is any better than Saint Augustine, who once said:

“What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.”

However, Einstein’s relativity posits a type of time that is no longer absolute and eternal, but varies according to the framework of representation, that is to say, depending on the measurement. Proust demonstrates an intuition similar to that of the eminent physicist in his description of the church in Combray:

“[All] these things made [it]… a building which occupied, so to speak, four dimensions of space – the name of the fourth being Time.”

This reference to a four-dimensional space clearly echoes the concept of relativity. But was Proust familiar with Einstein’s theory? When asked this question years later, he explained himself in a letter:

“Although it has indeed been written to me that I derive from him, or he from me, I do not understand a single word of his theories, not knowing algebra. And I doubt for my part that he has read my novels. It seems we have analogous ways of deforming Time.”

A quantum view of reality

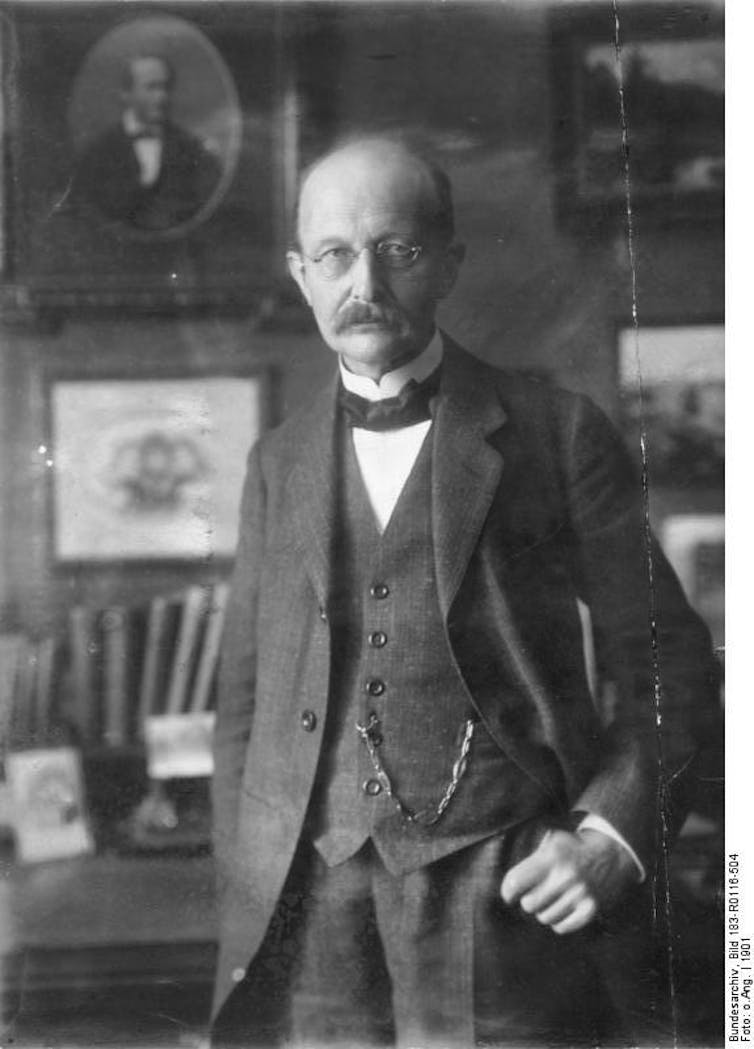

Less apparent in the text are Proust’s dabblings in quantum mechanics. The then-nascent theory based on quanta – primary corpuscles of energy – was first proposed by Max Planck in 1900.

While attempting to comfort his sick grandmother, the narrator nods to this new idea in physics:

“[According] to the latest scientific discoveries, the materialist position appeared to be crumbling.”

Which discoveries does he have in mind here? We can only assume that he is speaking of quantum mechanics. Proust’s contemporary, Paul Valéry, also born in 1871, appears to evoke this same scientific theory. In Reflections on the World Today (1929), he writes:

“[The light] is compromised… in the suit brought by discontinuity against continuity, probability against images… hidden reality against the mind that would track it down and, in a word, by the unintelligible against the intelligible.”

Quantum mechanics clashed with the way we traditionally viewed the world. Classical physics is deterministic; we can use it to predict how things will happen. We can understand reality “for what it is”. However, with an electron, all we can do is calculate the probability of it making a given journey. In this way, determinism becomes collective, as we are aware of the distribution of a group of electrons but do not know where any particular one of them will end up. Quantum theory, which governs these behaviours, is a branch of physics that sometimes appears counterintuitive.

It relies on two seemingly contradictory postulates:

The Schrödinger equation, which regards evolution, is deterministic in nature. It is a dynamic law governing forces other than gravity, much like a more precise version of Newton’s law of universal gravitation.

However, quantum theory also includes the principle of “collapse,” which applies at the moment of measurement and chooses the result from among an infinite set of possibilities.

Proust flirts with this quantum paradox, writing:

“She acquired an almost beggarly air from having (in place of the ten, the score that I recalled in turn without being able to fix any in my memory) but a single nose, rounder than I had thought, which made her appear rather a fool and had in any case lost the faculty of multiplying itself… Fallen into the inertia of reality, I sought to rebound.”

He contrasts the multiple image that he keeps of this young dairymaid character with the sole reality that he offers himself, such that his vision “collapses” in the real world.

While quantum mechanics reveals a probabilistic material reality, Proust believes in the spiritual reality of human beings, musing that “other people exist for us only to the extent of the idea that we retain of them” and “the evidence of the senses is also an operation of the mind in which conviction creates the evidence”.

Quantum reality is dependent on the measurement made by the observer, similar to how any observation engenders a subjective mental translation: “[Reality] has no existence for us, so long as it has not been created anew by our mind.”

In Search of Lost Time is a magnificent compendium, laden with humour, emotion, poetry and philosophy. As Proust peppers his writing with the ingredients of real life, the laws of physics nestled into his run-on sentences are more than merely decorative. He filters the world through an Impressionist vision of reality, not unlike the teachings of quantum mechanics.

Although many experts have regarded Proust as the greatest French writer of the 20th century, he was awarded no Nobel Prize, his ashes are not enshrined in the Panthéon, and no waxwork of him haunts the Musée Grévin. But he was ahead of his time, taking comfort in such macabre matters:

“[There] is no reason inherent in the conditions of life on this earth that can make us consider ourselves obliged to do good… nor make the talented artist consider himself obliged to begin over again a score of times a piece of work the admiration aroused by which will matter little to his body devoured by worms… All these obligations which have not their sanction in our present life seem to belong to a different world… So that the idea that Bergotte was not wholly and permanently dead is by no means improbable.”

And so, too, did Proust enter this ideal realm that he had once wished for his fictional writer.

Translated from the French by Enda Boorman for Fast ForWord.

François Vannucci ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.