Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

What do astronomers have to say about the Moon landing conspiracy theories? – Prisha M., age 14, Mumbai, India

Back in 1969 – more than a half-century ago – Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the Moon.

At least that’s what most people think.

But a few still insist that humans did not land on the Moon.

Should you believe them? How can you know that astronauts really did go to the Moon?

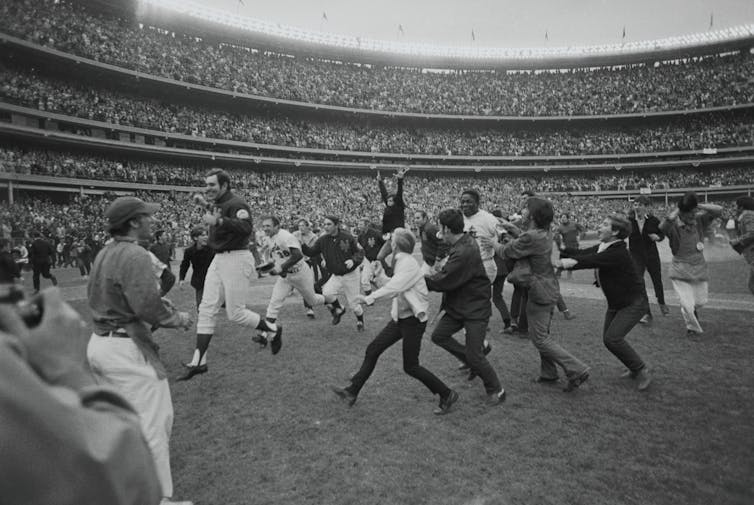

Let’s address this question by putting it side by side with another stunning event of the same year: the New York Mets’ shocking win in baseball’s World Series. They beat the Baltimore Orioles, four games to one.

Another miracle

But how do you know that? How can you be sure? After all, up until 1969, the Mets were a terrible team. They won the fewest games in the major leagues in 1967, and the third-fewest in 1968. It seems very unlikely they could have won the championship the very next year.

What if someone said that it didn’t happen? That the Mets instead lost the series to the Orioles? That the claim the Mets won is just a hoax, a canard, a fake story?

Is it possible to prove they’re wrong?

Seen on TV

First: Millions of Americans watched the World Series on television – approximately 11 million to 17 million viewers per game, according to Nielsen ratings. Many of those people are still alive today and remember seeing the Mets win.

Why would all of them lie? That doesn’t make sense.

Now consider this: More than 600 million people around the world watched the Moon landing on TV.

Seen at stadiums

But a skeptic might say “so what” – maybe the entire World Series was somehow faked, re-created in a TV studio.

Yet ticket records document more than 250,000 people saw the games in person. Along with them were hundreds of TV, radio and newspaper reporters and support personnel who also witnessed the action directly. Many of them are still alive today, and every one of them agrees that the Mets won.

Why would all of them lie? That doesn’t make sense.

Now consider this: More than 400,000 people worked on the Apollo program – scientists, engineers, researchers and support staff along with the astronauts.

Even the opposition agreed

So a skeptic might claim the New York media, or some other corporate entity, set up fake broadcasts and fake fans for some nefarious purpose. And the reason no one talks – well, maybe everyone was paid off.

Although the New York newspapers and TV stations may have wanted the Mets to win, the Baltimore reporters and broadcasters, and especially the players and fans, did not.

Yet all of them – even the players – admitted their team had lost. If the Series was a sham, why didn’t a single one of them who opposed the Mets expose the fraud?

Why would all of them lie? That doesn’t make sense.

Now consider this: The Soviet Union was the United States’ rival in the Space Race – it wanted to be the first on the Moon. But the Soviet government told its citizens on radio and television and in newspaper articles in July 1969 that U.S. astronauts had landed on the Moon. Soviet President Nikolai Podgorny even sent a telegram to U.S. President Richard Nixon offering his congratulations.

Score cards and Moon rocks

At this point, a skeptic might change tactics and say all of this evidence is just hearsay, and you can’t trust people.

But consider the hard physical objects preserved from the Series. At the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, you can find score cards and programs from the games, as well as the glove worn by center fielder Tommie Agee. All the objects can be dated to the year 1969.

Certainly, this is slightly weaker evidence; after all, it’s possible to produce fake printed items. And even if scientists found traces of Tommie Agee’s DNA in the glove, it would prove only that he wore it at some point that year, not necessarily that the Mets had won the Series.

But the physical evidence for the Moon landings cannot be faked so easily. First, the Moon rocks brought back by the Apollo astronauts are unlike rocks on Earth. And they are similar to lunar samples returned by Soviet and Chinese spacecraft. Scientists from many countries have examined these rocks and continue to study them today.

Second, the Apollo 11 astronauts placed mirrors on the Moon that have been detected for decades by telescopes in the U.S., France, Germany, South Africa and Australia. Anyone with a few million dollars can build a telescope big enough to see them.

There’s even more evidence we haven’t mentioned: the dozens of unmanned probes sent to the Moon by both the U.S. and the USSR before Apollo 11, which built up the technology needed for the landings; the large budget devoted to the project – NASA spent about US$49 billion on lunar missions between 1960 and 1973; and the universal agreement by scientific and academic institutions around the world for the past half-century that astronauts really did land on the Moon.

So why do some people continue to insist that humans never reached the Moon? Maybe they like to imagine they have “secret knowledge.” It makes them feel they’re just a bit smarter than everyone else. After all, a few still incorrectly claim the Earth is flat.

Now – what do you think? Did the Baltimore Orioles actually win the World Series in 1969? Has a worldwide conspiracy prevented millions of witnesses from coming forward to expose the hoax? Have citizens of the United States suffered from an episode of mass delusion?

Or did the Miracle Mets actually win the World Series in 1969?

The evidence – and your logic and common sense – will answer the question for you.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Michael Richmond does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.