With the recent build-up of Russian forces around Ukraine, Vladimir Putin’s claim that Russians and Ukrainians occupy “the same historical and spiritual space” has taken on an ominous tone. In the eyes of large swaths of the Russian political elite, these countries share the same roots, some even dispute the legitimacy of an independent Ukrainian state.

But the two most influential republics of the former Soviet Union have taken different paths since 1991. Whereas the Russian elite has struggled to accept its loss of oversight in the “near abroad”, Ukrainians have largely embraced their country’s independence.

Over the past decade, Russia and Ukraine have also drifted apart in how they view their shared past. In 2015, for example, Kyiv passed legislation equating communism with Nazism, whereas in 2014, Russia adopted a law criminalising criticism of the Soviet Union’s actions in the second world war. Today, politicians on both sides continue to dwell on the past, hurling epithets such as “Banderite” and “Putler” at one another as they couch present-day politics in historical analogies.

But what do ordinary Russians and Ukrainians make of the complex historical legacies that link the two countries? In early 2021, the Berlin-based Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS) conducted a comparative study of Ukrainian and Russian views regarding history. We surveyed 2,000 individuals in each country. Respondents ranged in age from 18 to 65, resided in communities of over 20,000 inhabitants, and were representative of the underlying population in terms of gender, age and place of residence.

Desire for shared views on history

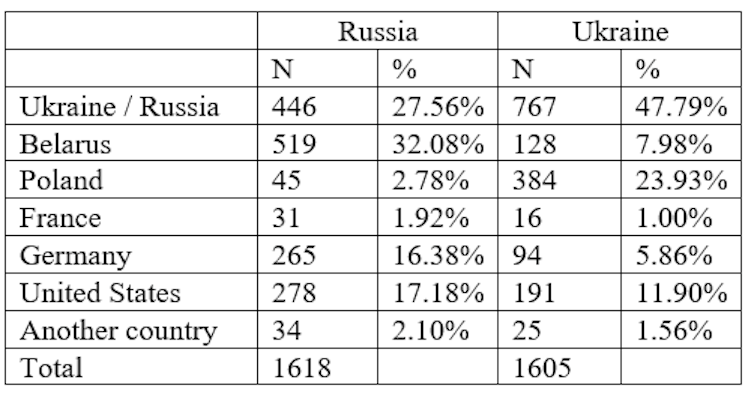

If Russians and Ukrainians are asked to name another country that their own should share common historical views with, Ukrainians overwhelmingly mention Russia as their first choice. For Russians, meanwhile, Ukraine places second after Belarus. Despite the ongoing geopolitical confrontation between these two states, there remains a desire for historical dialogue at the societal level.

But when Russians accord Ukraine a high level of importance for shared historical views, this does not imply they accept Ukraine as a distinct nation. Geopolitics and the perceived importance of states figure clearly in such assessments. Tellingly, Russians rank the United States and Germany prominently – countries with different historical views and political importance. Similarly, Ukrainians rank Poland highly, reflecting past ties to Warsaw but also current regional dynamics.

Question: In your view, with what country is it most important to have similar views on historical events?

Differing memories

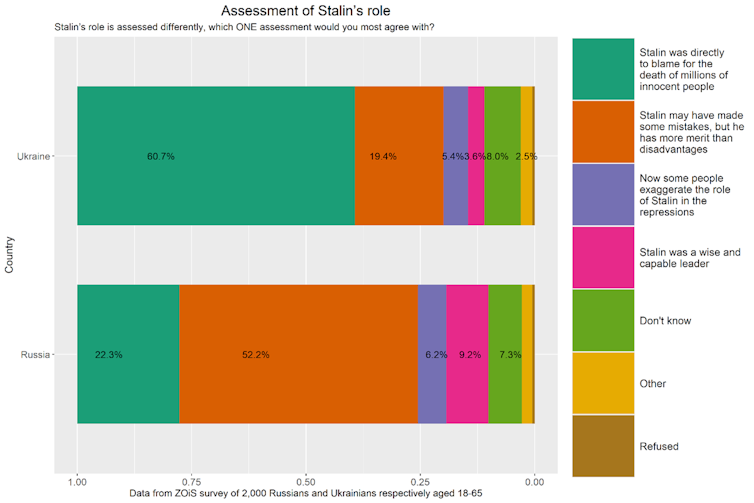

Profound differences exist in how historical leaders are seen in these countries. In particular, the memory of Josef Stalin has been conflated in Russia with the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany. As a result, Stalin’s contributions to the war and the USSR’s socioeconomic development are stressed. The atrocities that occurred during his reign, meanwhile, are increasingly downplayed.

Our survey identifies a striking divergence of opinions about Stalin. A clear majority of Ukrainians hold unambiguously negative views, with 60% stating that he was directly to be blamed for the death of millions of innocent people. In Russia, however, 52% believe that he had more merit than disadvantages and another 9% say that he was a wise and capable leader.

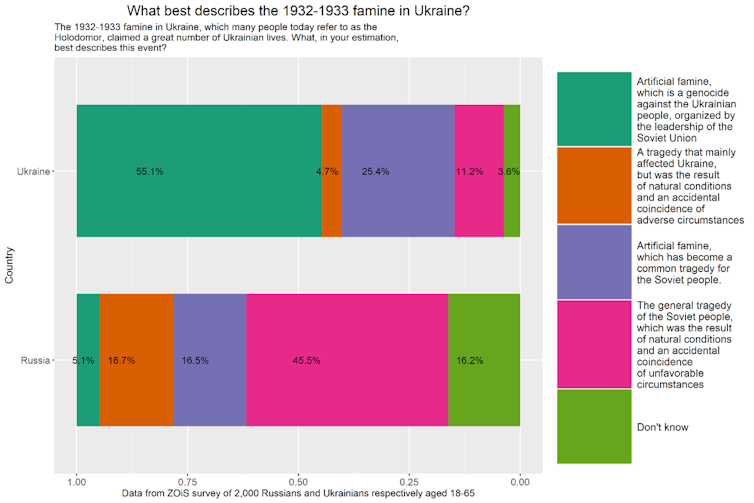

Assessments of historical events also differ fundamentally. For instance, the Ukrainian famine of 1932-1933, also known as the “Holodomor”, has rapidly become a central component of Ukrainian identity. Today, 55% of Ukrainians understand the Holodomor as an artificial famine orchestrated by the Soviet authorities and directed against Ukrainians, a view held by just 5% percent of Russians. In Russia, on the other hand, it is most frequent to view the famine as a common tragedy of the Soviet people and attribute its inception to unfavourable natural conditions.

In Ukraine, the Holodomor has been depicted by nationalist and western-leaning politicians – prominent among them former president Viktor Yushchenko – as an attempt to destroy a freedom-loving ethnicity. Ukraine’s parliament passed a resolution in 2006 recognising the Holodomor as a genocide against the “Ukrainian people”. In this manner, the famine has come to symbolise Ukraine’s long struggle to gain independence from Russian, and later Soviet, colonisation.

The Soviet era

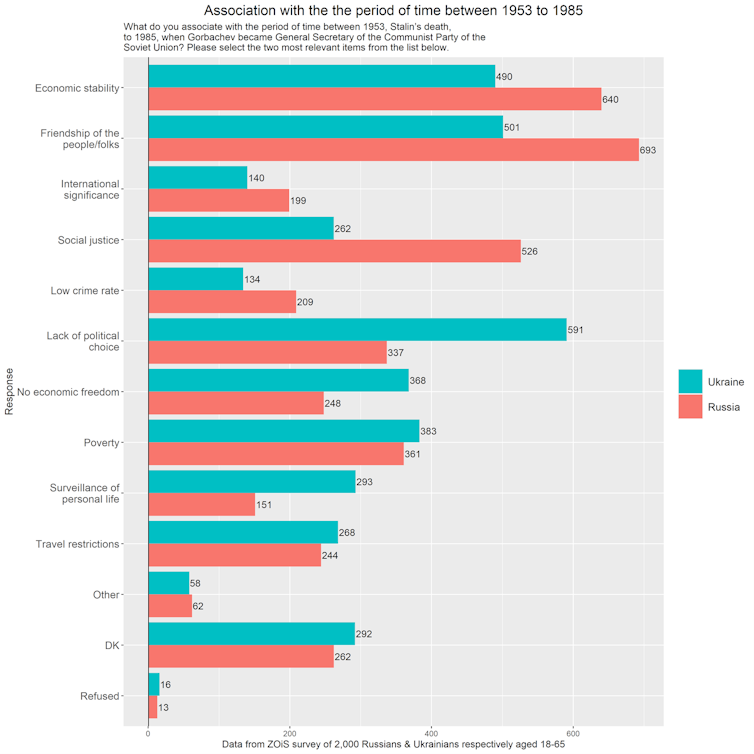

Provided with several positive and negative associations about the Soviet period more general, Russians universally mention the positive associations more frequently and Ukrainians the negative ones. For example, the themes of social justice, friendship between peoples, and economic stability all are more likely to be projected positively onto the Soviet period by Russians.

Concurrently, the lack of political choice, which Russians do not mention prominently, is most frequent among Ukrainians. Ukrainians also mention other negative associations, such as the lack of economic freedom and the surveillance of personal life, more often than Russians. There is a generational component to this, with younger Ukrainians being more positive about the Soviet Union’s dissolution compared to their peers in Russia.

The current confrontation between Russia and Ukraine is underpinned by deep divergence in views over history, both at the elite and societal levels. But while there remains some support in Ukraine for the idea of the two countries being “one people”, the percentage of Ukrainians who would like the two states to unite has slipped into the low single digits.

What does this say about the future of relations between the two countries? On the one hand, there still appears to be a significant desire to settle on a common view of the past, which would suggest a willingness for dialogue. On the other hand, it is clear that diverging views on the past have become a key issue in the national self-understanding in both countries and that on both sides one has the impression the past should be defended.

Competing and highly emotional visions on shared historical legacies fuel the geopolitical confrontation we are currently witnessing between Moscow and Kyiv and, given how incompatible these different perspectives on history are, they become even harder to resolve as a geopolitical confrontation unfolds.

Félix Krawatzek is Senior Researcher at the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS), an independent research institute funded by the German government, and an Associate Member of Nuffield College, University of Oxford. The survey referred to in this article was financed through a postdoctoral scholarship granted to Félix Krawatzek by the Daimler and Benz Foundation.

George Soroka does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.