Uber is courting its arch enemy, London black cabs, inviting them to add their services to its app for the first time. Licensed taxis in 33 countries, including France and the US, have already received similar invitations. According to Uber this has brought significant new trade to traditional taxis.

It is not clear that black cabs accepting this offer will see much benefit, however – and sure enough their trade association has put out a statement to say that most will not be participating. Black cabs’ main advantages over apps like Uber are kerb hailing and taxi ranks, which are probably their biggest sources of income. They also have their own ride-hailing app and already feature on Uber rivals Bolt and FreeNow.

Indeed, appearing on Uber is only likely to emphasise the difference between their prices and those of other taxis on the app, as well as the fact that hackneys have more uncertain fares due to metering. There are also far more Uber cars in London, believed to be in the order of 45,000 compared with around 15,000 black cabs. And with so few hackneys likely to sign up, there will probably be very poor response times on the app from any that do.

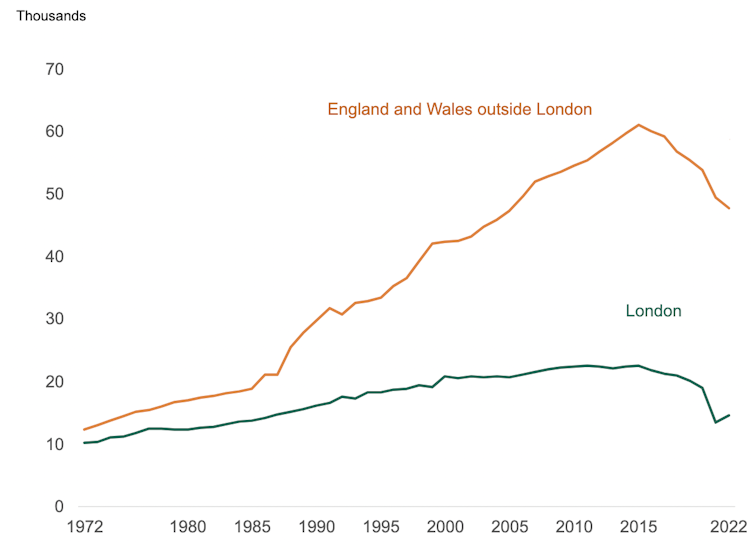

Since Uber arrived in London in 2012, the number of black cabs has fallen by about 6,000. Uber’s early cavalier approach to rules around insurance and driver ID led to Transport for London withdrawing its licence to operate in 2017 and then again in 2019. Uber won a new licence on appeal in 2022 after agreeing to overhaul its processes to ensure better driver compliance and passenger safety.

Black cabs and the Uber effect

The other side of the coin

The real benefit to listing hackneys probably resides with Uber, which will gain more “traffic” through its app. This might also boost demand for the Uber Eats takeaway delivery service and expose more people to adverts on the company’s apps. (In the US, advertising has become a major source of revenue for Uber.)

Does Uber make money at present? In its 14-year history, profitability has tended to seem distant at best. There are no accounts available for the UK operation, but US parent company Uber Technologies lost US$9.1 billion (£7.2 billion) in 2022 after writing down the value of various things on its books, primarily investments.

The ride-hailing business did make an underlying pre-tax profit of US$1.1 billion for the year, and has also been doing well in 2023, though the most recent third-quarter results show that this is still more than offset by the continuing losses at Uber Eats.

It is difficult finding anyone in the takeaway delivery business who makes money. In the US, DoorDash dominates with around 65% market share (compared to Uber’s 23%). It is growing rapidly, and yet still making losses. Meanwhile, in the UK, Deliveroo is showing substantial losses whilst growth has slowed to a crawl.

It’s very tough in takeaway delivery because of the fierce competition and the fact that the restaurants are low-margin already. The scope is limited by what customers will pay for often lukewarm fare. Restaurants can also handle their own deliveries to avoid the apps’ heavy charges. Even among those who use the apps, it’s not uncommon for them to offer marginally better deals to customers who order through their website or call in.

As for ride-hailing, the economics are challenging, to say the least. Drivers’ costs are rapidly increasing in everything from insurance to vehicles, particularly electric ones, which all have to be passed on to customers. Rapidly increasing minimum wage levels are driving up prices too.

In London, Uber increased its fares in 2021 and 2022, then introduced “dynamic prices” in 2023 which will likely result in more increases. Coming at a time when consumers are being squeezed by higher interest rates and inflation, this may not be great for demand.

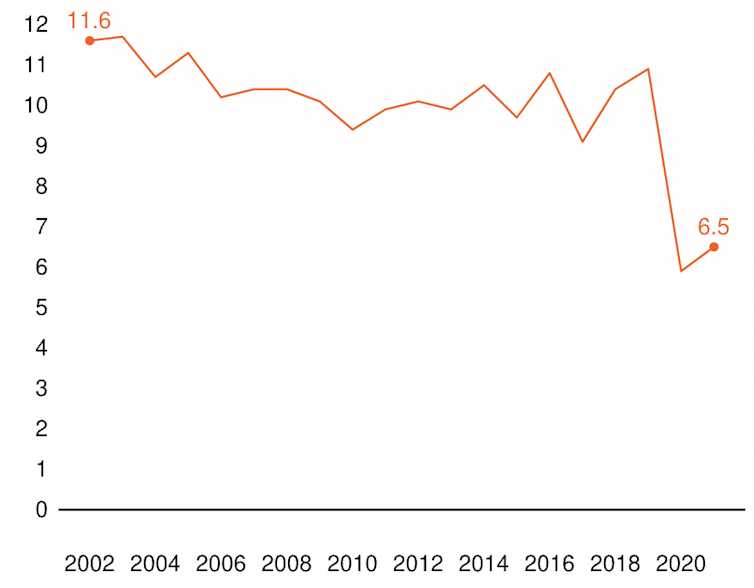

We’ve already seen taxi demand diminishing significantly in England in recent years, albeit it’s hard to separate the effect of price rises from increased working from home since the pandemic.

Taxi rides per person per year, England

In big cities, customers’ sensitivity to higher fares is liable to be heightened by the availability of good public transport. On the flip side, the Department for Transport has pointed out that the rise in driver numbers in London from 95,000 to 105,000 between 2022 and 2023 may be an indication that customer demand has been rising in recent months.

Overall, however, it’s difficult to see ride-hailing apps making much money while costs keep rising. And even if this sector did become particularly profitable in future, competition would soon increase. The technology is widely available and drivers have shown they will accept business from anyone offering good rates. All you need to do is persuade customers to download your app.

Uber and society

The number of cabs in London has now doubled since the arrival of Uber over a decade ago. This suggests that many passengers have in effect been lured from public transport and healthy options such as walking and cycling.

About half of Uber’s London taxis still seem to be conventional combustion engines, so their popularity will also have increased pollution and carbon emissions. That has to be balanced against the fact that some 50,000 drivers may not otherwise have been employed and that it has made taxis a bit cheaper.

With takeaway delivery apps, the environmental impact is less because many deliveries are on bikes or electric bikes. However, the ready convenience of fast food cannot be good for a nation battling an obesity epidemic.

So there you have it. A business that will probably always struggle to make money and isn’t doing the world much good. As Uber turns for support to an industry it has squeezed so much, it will be hard to feel much sympathy if it doesn’t succeed.

John Colley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.