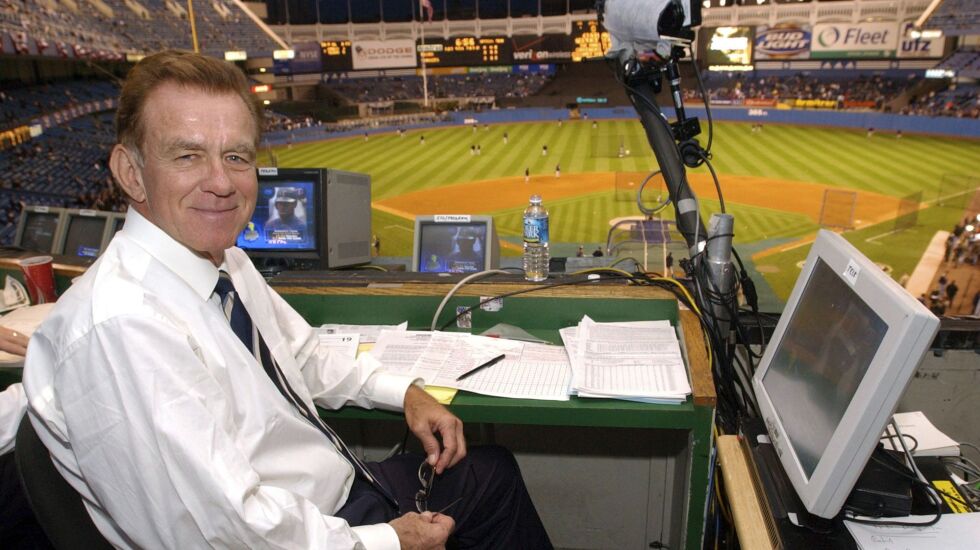

NEW YORK — Tim McCarver, the All-Star catcher and Hall of Fame broadcaster who during 60 years in baseball won two World Series titles with the St. Louis Cardinals and had a long run as the one of the country’s most recognized, incisive and talkative television commentators, died Thursday. He was 81.

McCarver’s death was announced by baseball’s Hall of Fame, which said he died Thursday morning in Memphis, Tennessee, where he was with his family.

Among the few players to appear in major league games during four different decades, McCarver was a two-time All Star who worked closely with two future Hall of Fame pitchers: The tempestuous Bob Gibson, whom McCarver caught for St. Louis in the 1960s, and the introverted Steve Carlton, McCarver’s fellow Cardinal in the ‘60s and a Philadelphia Phillies teammate in the 1970s. He switched to television soon after retiring in 1980 and became best known to national audiences for his 18-year partnership on Fox with play-by-play man Joe Buck.

“I think there is a natural bridge from being a catcher to talking about the view of the game and the view of the other players,” McCarver told the Hall in 2012, the year he and Buck were given the Ford C. Frick Award for excellence in broadcasting. “It is translating that for the viewers. One of the hard things about television is staying contemporary and keeping it simple for the viewers.”

MLB Network mourns the passing of Hall of Famer Tim McCarver. pic.twitter.com/aGLoLT2iLV

— MLB Network (@MLBNetwork) February 16, 2023

Six feet tall and solidly built, McCarver was a policeman’s son from Memphis, who got into more than a few fights while growing up but was otherwise playing baseball and football and imitating popular broadcasters, notably the Cards’ Harry Caray. He was signed while still in high school by the Cardinals for $75,000, a generous offer for that time; just 17 when he debuted for them in 1959 and in his early 20s when he became the starting catcher.

McCarver attended segregated schools in Memphis and often spoke of the education he received as a newcomer in St. Louis. His teammates included Gibson and outfielder Curt Flood, Black players who did not hesitate to confront or tease McCarver. When McCarver used racist language against a Black child trying to jump a fence during spring training, Gibson would remember “getting right up in McCarver’s face.” McCarver liked to tell the story about drinking an orange soda during a hot day in spring training and Gibson asking him for some, then laughing when McCarver flinched.

“It was probably Gibby more than any other Black man who helped me to overcome whatever latent prejudices I may have had,” McCarver wrote in his 1987 memoir “Oh, Baby, I Love It!”

Few catchers were strong hitters during the ‘60s, but McCarver batted .270 or higher for five consecutive seasons and was fast enough to become the first in his position to lead the league in triples. He had his best year in 1967 when he hit .295 with 14 home runs, finishing second for Most Valuable Player behind teammate Orlando Cepeda as the Cards won their second World Series in four years.

McCarver met Carlton when the left-hander was a rookie in 1965 “with an independent streak wider than the Grand Canyon,” McCarver later wrote. The two initially clashed, even arguing on the mound during games, but became close and were reunited in the 1970s after both were traded to Philadelphia. McCarver became Carlton’s designated catcher even though he admittedly had a below average throwing arm and overall didn’t compare defensively to the Phillies’ regular catcher, Gold Glover Bob Boone.

“Behind every successful pitcher, there has to be a very smart catcher, and Tim McCarver is that man,” Carlton said during his Hall of Fame induction speech in 1994. “Timmy forced me pitch inside. Early in my career I was reluctant to pitch inside. Timmy had a way to remedy this. He used to set up behind the hitter. There was just the umpire there; I couldn’t see him (McCarver), so I was forced to pitch inside.”

McCarver liked to joke that he and Carlton were so in synch in the field that when both were dead they would be buried 60 feet, six inches apart, the distance between the rubber on the pitching mound and home plate.

During a 21-year career, when he also played briefly for the Montreal Expos and Boston Red Sox, McCarver batted .271 overall and only twice struck out more than 40 times in a single season. In the postseason, he averaged .273 and had his best outing in the 1964 series, when the Cards defeated the New York Yankees in seven games. McCarver finished 11-for-23, with five walks, and his 3-run homer at Yankee Stadium in the 10th inning of Game 5 gave his team a 5-2 victory.

Younger baseball fans first knew him from his work in the broadcast booth, whether local games for the New York Mets and New York Yankees, as Jack Buck’s partner on CBS or with son Joe Buck for Fox from 1996-2013. McCarver won six Emmys and became enough of a brand name to be a punchline on “Family Guy”; write a handful of books, make cameos in “Naked Gun,” “Love Hurts” and other movies and even record an album, “Tim McCarver Sings Songs from the Great American Songbook.”

Knowledge was his trademark. In his spare time, he visited art museums, read books and could recite poetry from memory. At work, he was like a one-man scouting team, versed in the most granular details, and spent hours preparing before each game. At times, he seemed to have psychic powers. In Game 7 of the 2001 World Series, the score was tied at 2 between the Yankees and the Arizona Diamondbacks and the Yankees drew in their infield with the bases loaded and one out in the bottom of the 9th. Relief ace Mariano Rivera was facing Arizona’s Luis Rodriquez.

The Hall of Fame remembers 2012 Frick Award winner Tim McCarver, who passed away on Thursday.https://t.co/Np1cTyEJbV pic.twitter.com/ydNjOJqrBY

— National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum ⚾ (@baseballhall) February 16, 2023

“Rivera throws inside to left-handers,” McCarver observed. “Lefthanders get a lot of broken-bat hits into shallow outfield, the shallow part of the outfield. That’s the danger of bringing the infield in with a guy like Rivera on the mound.”

Moments later, Gonzalez’s bloop to short center field drove in the winning run.

“When you the consider the pressure of the moment,” ESPN’s Keith Olbermann told The New York Times in 2002, “the time he had to say it and the accuracy, his call was the sports-announcing equivalent of Bill Mazeroski’s home run in the seventh inning to defeat the Yankees in 1960.”

Many found McCarver informative and entertaining. Others thought him infuriating. McCarver did not cut himself short whether explaining baseball strategy or taking on someone’s performance on the field. “When you ask him the time, (he) will tell you how a watch works,” Sports Illustrated’s Norm Chad wrote of him in 1992. The same year his criticism of Deion Sanders for playing two sports on the same day led to the Atlanta Braves outfielder/Atlanta Falcons defensive back’s dumping a bucket of water on his head. In 1999, he was fired by the Mets after 16 seasons on the air.

“Some broadcasters think that their responsibility is to the team and the team only,” McCarver told The New York Times soon after the Mets let him go. “I have never thought that. My No. 1 obligation is to the people who are watching the game. And I’ve always felt that praise without objective criticism ceases to be praise. To me, any intelligent person can figure that out.”

McCarver and his wife, Anne McDaniel, had homes in Sarasota, Florida, and Napa, California. In recent years, McCarver announced part-time for Fox Sports Midwest and worked the occasional Cards game before sitting out the 2020 season because of concerns about COVID-19. Besides the Frick award, he was inducted into the Cardinals Hall of Fame, in 2017.

“By the time I was 26 I had played in three World Series and I thought, ‘Man this is great, almost a World Series every year,” he said during his acceptance speech. “Uh-uh. The game has a way of keeping you honest. I never played in another World Series.”