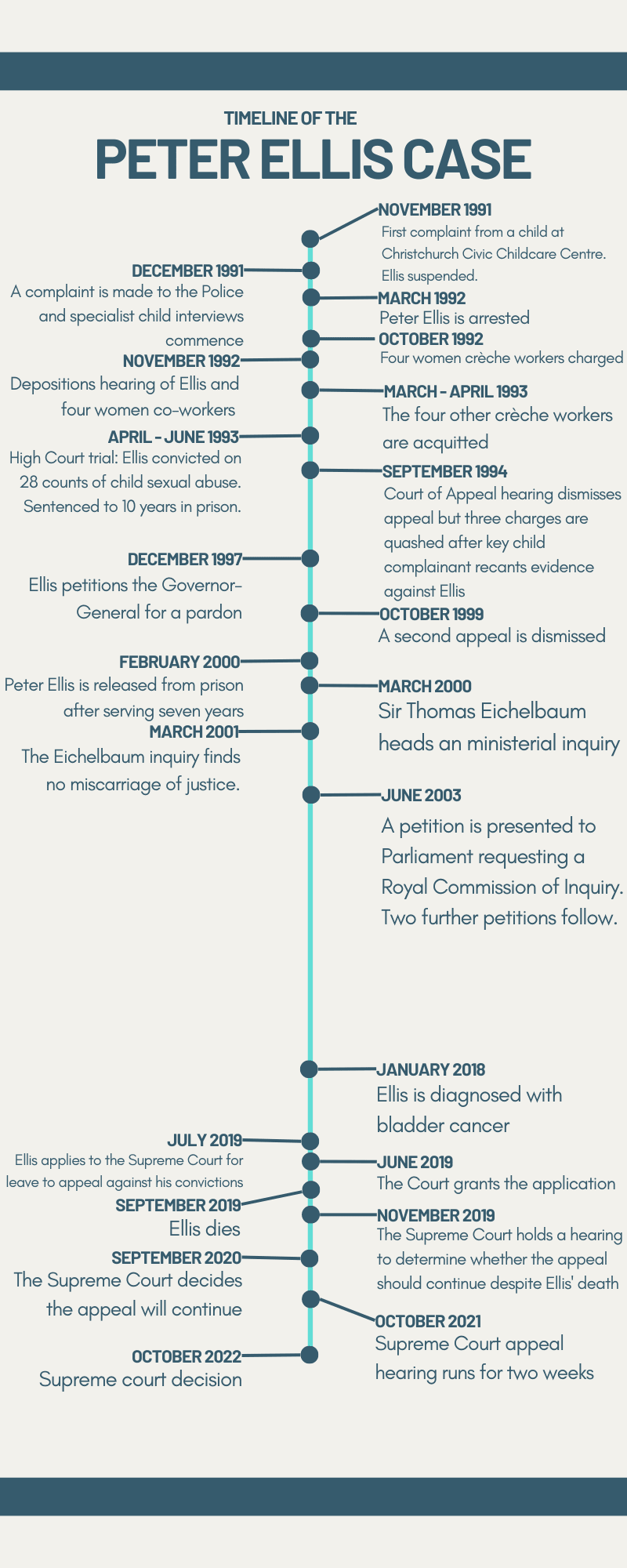

On Friday the Supreme Court will deliver what could be a groundbreaking judgment on an appeal in one of the country's most extraordinary cases - Peter Ellis' conviction in the Christchurch Civic Creche child abuse case. Bonnie Sumner and Melanie Reid explain what's at stake.

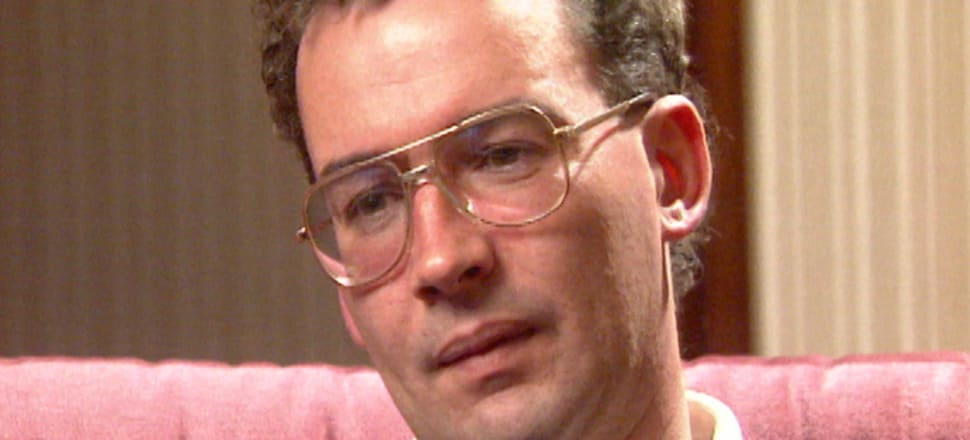

On June 5, 1993, Peter Ellis, an exuberant, funny and unfailingly polite childcare worker, was convicted on 16 counts of sexual abuse against seven children in his care. He always maintained his innocence. After three decades as a convicted child abuser and then his death in 2019, tomorrow a landmark Supreme Court decision will be released that could clear Ellis’ name.

It’s the case that never goes away. Despite his death from bladder cancer three years ago, Peter Ellis' name lives on in the courtroom, in the media, and in the collective mind of the nation.

He spent seven years in jail as a result of his convictions, but steadfastly maintained his innocence up until his death.

Tomorrow, after Ellis and his supporters spent three decades trying and failing to prove his innocence, the nation will know whether he has finally been exonerated in an unprecedented posthumous finding that involved an unusual argument suggested by the Supreme Court justices themselves: tikanga Māori.

But the question remains - how did this ever happen in the first place?

Back in the early 1990s before he was convicted, journalist Melanie Reid secretly interviewed Ellis in a string of rundown Christchurch motels while his case was still sub judice.

Newsroom Investigates has dusted off these extraordinary never before seen interviews in a brand new in depth series Peter Ellis, the creche case and me launching on Monday that unravels the hysteria that allowed the conviction of a young gay man and a trail of destruction that continues to this day.

At the time, Ellis, fresh faced with curly hair and eyeliner, held an unwavering belief the truth would prevail.

“The thing people don’t understand about Peter is he was very well brought up and polite and believed in the police and the establishment, and even up to the end he was still polite about them, even though they had sent him to prison,” says Reid.

In one of these motel videos, he told Reid: “I hope one day that they are actually going to be prepared to come along and say, ‘Hello Peter, can you tell me, did we get it wrong?’ And I’ll tell them, they got it wrong, because it didn’t happen.”

Tomorrow, we will know if they got it wrong. But it will be too late to tell Peter Ellis.

Homophobia and hysteria

Ellis’ conviction has haunted this country ever since the three-year-old son of a social worker told his mother he didn’t like “Peter’s black penis” in late 1991.

The Homosexual Law Reform Bill had only been passed into law in 1986, which legalised sex between men. Then Minister of Internal Affairs, Graeme Lee, at the time described homosexuality as “unarguably an unnatural behaviour,” adding, “surely it stands to reason there is a predilection to paedophilia or child sex."

As a gay man in a time and place known for its conservatism, Ellis stood out – and a tornado was gathering that would sweep him and dozens of children, parents and colleagues into its vortex.

What followed has been described as a witch hunt, a climate of hysteria - and Christchurch dubbed ‘a city possessed’, the title of author Lynley Hood’s seminal book on the saga.

(One reviewer described Hood’s book as “…one of the best true crime books ever written about crimes that never happened.”)

After the first mother became convinced her child was being abused - a child who never ended up making any formal disclosures - a core group of parents got together and grilled their young children.

Before Ellis was convicted, over a hundred children would be put through evidential interviews, which turned up a multitude of outlandish and fantastical revelations that included Ellis cooking kittens as well as digging up Jesus Christ, poking sticks up children’s bottoms and allowing a child to be run over and killed. A number of children were also put through invasive medical examinations, which did not yield any definitive signs of abuse.

A belief that satanic ritual abuse was being conducted against children by childcare workers had already been spreading through childcare centres in California, Canada, Europe and Brazil. Dozens of workers were arrested, and some spent decades in prison as a result before being cleared of any wrongdoing.

After Ellis’ initial arrest, the police and specialist interviewers came to the conclusion other workers at the creche were also involved, and four women, including creche supervisor Gaye Davidson, were arrested and charged with indecent assault and sexual violation.

Ellis and the other workers from the Christchurch Civic Creche presented the perfect targets for a New Zealand attempt at blowing the lid on a paedophile ring. (Nevermind actual cases of child abuse that were being actively ignored by police and the state, such as Auckland’s Centrepoint commune and numerous state run homes and religious institutions now the subject of the Abuse in Care Inquiry.)

In March and April 1993 following depositions, the women were acquitted, so they were discharged and Ellis found himself facing trial alone.

“They got rid of the women because…they would find it easier to convict Peter on his own than they would to convict the four of us,” Davidson told Newsroom.

She said getting rid of the charges meant a much clearer path to secure a conviction. “I think it’s easier to believe a male would do that rather than the women doing it.”

“And I think a lot of people would have lost face, the police, the social workers, the professionals that were driving it, and they couldn’t afford for him not to be convicted. The ramifications even financially for them would have been huge, too.”

Ellis was sentenced to 10 years in prison. When the jury handed down the verdict, Justice Williamson, said, “Unlike those who publicly feasted on this case, the jury had seen all the evidence available and had believed the children…and I agree with that finding.”

There was no physical or medical evidence ever presented. Out of the hundreds of hours of evidence from more than 100 children put through sometimes multiple formal interviews, in the end Ellis’s conviction was secured on the testimony of the interviews of seven children.

A creche parent, who cannot be identified, explained the hysteria of the time to Melanie Reid in an interview in the 1992: “I thought for a long time that people were looking for the truth and I don't think they were, I think they were looking for a monster.”

Attempts to clear his name

Throughout the whole ordeal, right up until his death, Ellis was concerned about the children and the effect the case had on them, saying it was one of the reasons he kept battling on. In an interview with Reid in 2001 he said he wished people could remove the emotions.

“I have spent years fighting for them just as much as I have been fighting to clear my name ... that is what being a childcare worker is, standing up and saying to the children it didn’t happen and it’s not fair on you and it's not fair on your parents."

Over the years Ellis submitted appeals and petitions, but they all came to nought.

His first go at clearing his name was a 1994 appeal to the Court of Appeal, a year after he was jailed. Sensationally, before it was due to begin, one of the seven complainant children - described as the oldest and most reliable - recanted.

In an exclusive interview published earlier this year, Newsroom spoke to the parents of that child.

“There was something about the craziness of that time. It sucked us in,” the mother explained. “I do believe our daughter was a victim, not of Peter Ellis, but of a system that really pressured her.”

Three convictions relating to her allegations were quashed, but the Court of Appeal dismissed Ellis’ appeal and he remained in jail.

In 1999 a second Court of Appeal attempt to clear his name was dismissed. Three petitions for a royal pardon were also declined.

Ellis was released in 2000 after completing his sentence, and a month later an inquiry was established by the government. Known as the Eichelbaum inquiry, it wasn’t the more comprehensive commission of inquiry Ellis had hoped for, and would be heavily criticised for its narrow scope. It found there had been no miscarriage of justice.

Ellis’ very last attempt was a Hail Mary months before his death, using an argument based on “Aotearoa’s first law,” as Supreme Court Justice Joe Williams has described tikanga. Never before used for a Pākehā, Peter Ellis has ended up representing a landmark case for our legal system.

Tikanga and the Supreme Court

In his last ditch push for justice, Ellis, sick with terminal cancer, approached the defence lawyer from his original case, Rob Harrison.

Could they seek leave to appeal against his convictions to the Supreme Court? Harrison agreed to give it a shot.

Much to the surprise of both Harrison and Ellis, and despite all the previous failed appeals, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

But the wheels of justice were too slow. Ellis died on September 4, 2019, five weeks before his scheduled hearing.

Usually, this would also mean the end of his legal case. But, as Harrison explained to Newsroom, as a longtime supporter of Ellis, he had to keep going.

Even in death, Ellis’ presence haunts the psyche of this country. His groundbreaking case is the first time a conviction has been appealed by a dead person in Aotearoa. And it was all due to the Supreme Court justices themselves, with Justice Susan Glazebrook suggesting the Crown address the “tikanga aspects” of the case.

Tikanga Māori is a holistic concept that describes, among other things, the values and protocols of te ao Māori. One of these customs is that a person’s mana is important not just in life but also in death – what might be described as their reputation or legacy.

The Supreme Court did accept the appeal on these grounds, but the case they have been considering since is multi-faceted. Tomorrow we will discover whether the Supreme Court regards tikanga as in fact part of Aotearoa New Zealand’s common law, and whether tikanga applied to Ellis’ case.

Second, we will know whether there was a miscarriage of justice in Ellis’ 1999 appeal decision, in particular whether Ellis was given a fair trial. This includes considering the way the evidence from the children was collected and used, the jury, a lack of expert evidence on the reliability of the children’s evidence, and unreliable expert evidence presented in Ellis’ trial.

At a press conference following his release from prison in 2000, Ellis told the waiting media pack: “I do not intend to stop until my name is cleared and the truth is out for everyone’s sake, including the children.”

Whatever happens tomorrow, it is a decision that no doubt will continue to be studied and pored over for decades to come, ensuring Ellis’ legacy lives on.