With 1980s, Damn The Torpedoes, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers would shoot to global acclaim. But, thanks to his stubborn, ruthless streak, he’d come under fire from his label, lawyers, fans and critics alike, almost being sunk in the defence of his artistic integrity

The following takes place between March 1980 and June 1981.

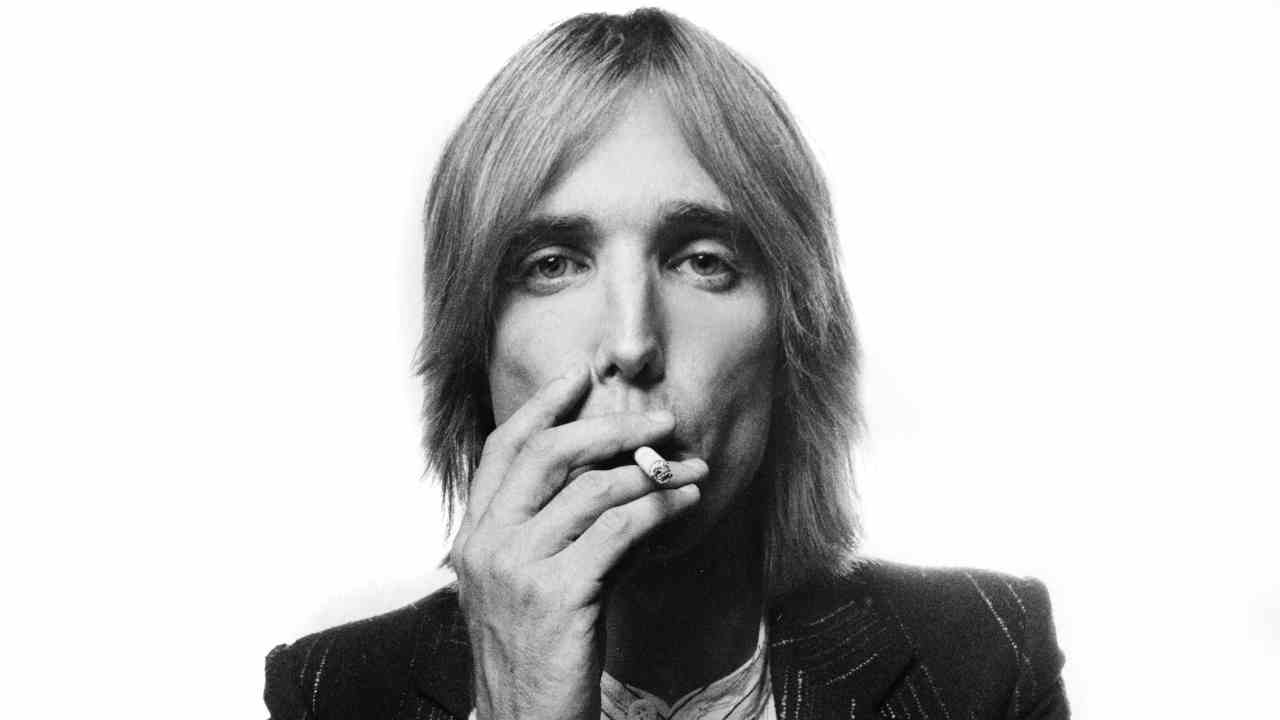

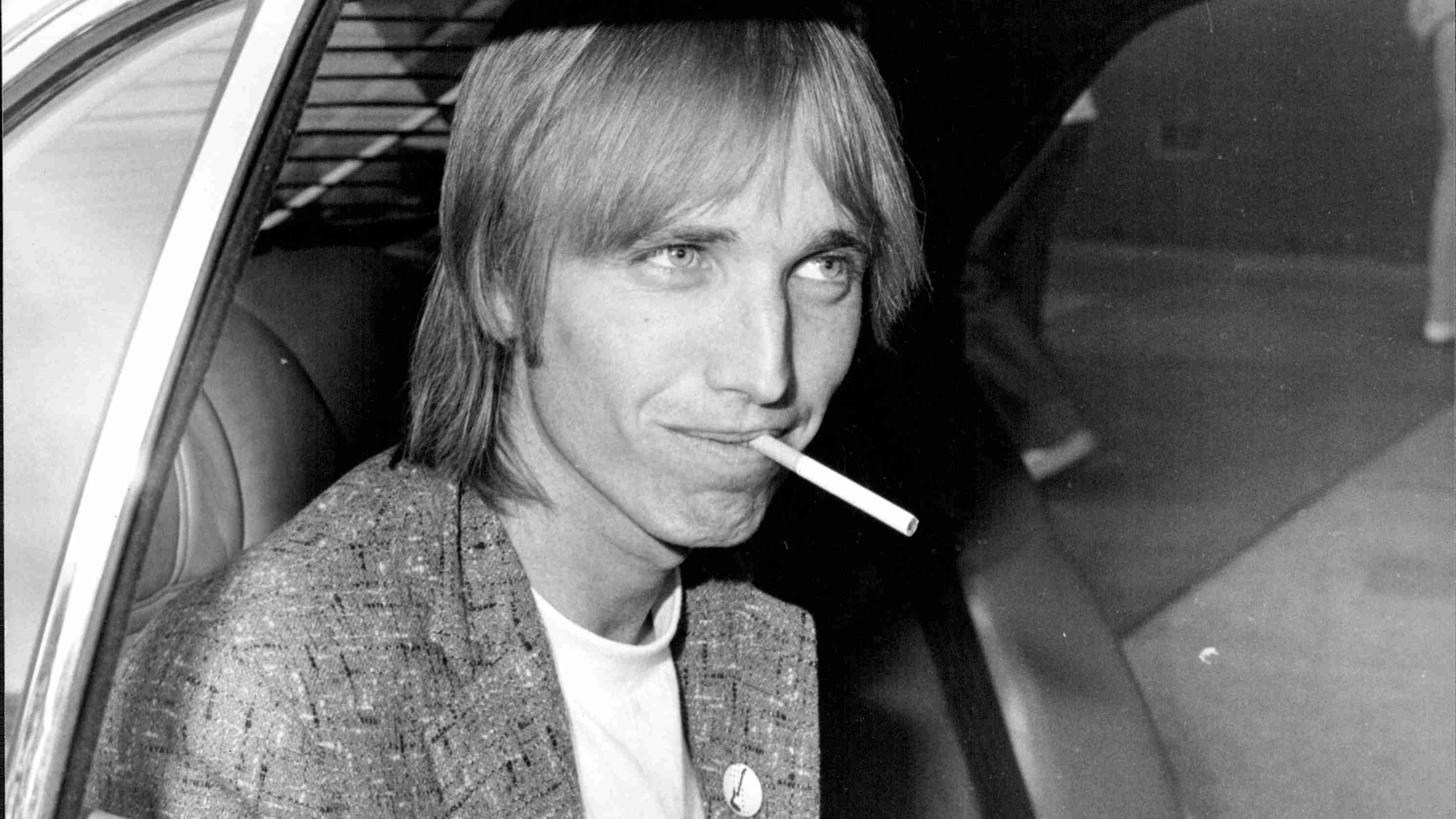

Part One: a seventh-floor hotel room in Knightsbridge. Tom Petty is sitting at a table drinking Coke and wishing it was Jack Daniel’s. He’s wearing an American Confederate jacket with one white star on the epaulette. He’s got a Joni Mitchell bone structure, straw-blond hair and a smile like a Gainesville gator. He looks androgynous and he can be ruthless. Like he was on March 7 and 8 at the Hammersmith Odeon when he berated the audience after an hour of polite British reserve with the taunt: “Are you all on fucking Mandrax?” And then slays them with When The Time Comes. It’s a riot now.

His most recent album, Damn The Torpedoes is at No.2 in the US chart but he can’t shift Pink Floyd off that pesky Wall. He also has two singles in the Top 30: Don’t Do Me Like That, written for J Geils Band – producer Jimmy Iovine would nix that – and Refugee, possibly his greatest song to that date. A third, Here Comes My Girl, is in waiting, buoyed by the line ‘It just seems so useless to have to work so hard and nothing ever really seems to come from it.’

So, damn the torpedoes and full steam ahead, as Rear Admiral David Glasgow Farragut ordered at the battle of Mobile Bay before scuppering the CSS Tennessee. In showbiz parlance, Tom Petty has arrived, with all that entails: the cover of Rolling Stone, features in Newsweek and what is euphemistically termed ‘heavy’ management.

It wasn’t always like this. Petty and his boys languished at Shelter Records from 1974 to 1977 when they were critical darlings, especially in the UK. The label, co-owned by Leon Russell and Denny Cordell, incorrigible rogues both, had a funky backwoods image, a small roster of idiosyncratic artists and homely promotional values that suited J J Cale but sank Dwight Twilley without trace. Petty liked the ambience but not the lack of ambition. He didn’t want shelter. He wanted the great wide open.

The Heartbreakers tour their debut album in Britain during the height of the new wave and find themselves labelled in a similar category, with Elvis Costello, Nick Lowe et al singing their praises. It’s a backhanded compliment that recognises Petty’s talents for offering something new by bracketing him with the punks like he’s spent his formative years in a mythical American garage, when his tastes are for classic LA rock, Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Atlantic soul and Stax R&B. But hey, anything that’s rock’n’roll’s fine. The second album, You’re Gonna Get It, isn’t understood by the critics. More of the same, they moan.

Throughout 1979, Petty is involved in a career-threatening lawsuit when Shelter sell their distribution to ABC, who promptly leap into MCA’s bed. Petty goes on strike. “I wasn’t consulted: no one asked me.” There are no tours and Damn The Torpedoes – an album recorded at a cost of $500,000 with Jimmy Iovine, Bruce Springsteen’s favourite engineer – is put on ice by the American High Courts when the singer declares himself bankrupt.

Prior to its release, Petty’s artistic life was shrouded in compromise. “Our first album didn’t break for a year. We’d renegotiated a contract that said if Shelter was sold, we’d the right to leave. That happened. ABC sold Shelter to MCA in one of those huge mergers that happen every day. We assumed we were free. MCA said, ‘You ain’t.’ [This overlooks the fact that MCA already owned Shelter; they were simply in re-acquisition.]

“Well, being kinda stubborn, I agreed to deliver an album but wouldn’t take any money from them. I spent my own money making it and it was a very expensive record to make. Partly because of the lawsuits, it took ten months. Then in the middle of recording, MCA sued me, Shelter sued me, my publishing company sued me and so did a few other smaller people. MCA’s a big dog for an individual to fight. I had nine lawyers contesting each case. While that’s happening, I’ve got constant offers from other record companies that would make me blush to tell you here. [Columbia apparently offered to shred his MCA contract and give him a multimillion-dollar sweetener.]

“It reached the stage where it was almost funny. If I sing a song, do I own it? Me, the band and Jimmy Iovine were midway through and US Marshals were coming to the studio to steal the tapes, confiscate everything. We had to hide all the boxes, smuggle things in and out. I had to go on the stand and evade issues like, ‘What songs have you written? Recite the lyrics. Where are the tapes?’ [Petty’s guitar tech Bugs took them home every night, allowing Tom to plead ignorance in court as to their whereabouts without perjury.] All they could do was beat me up mentally until I did it their way.

“Eventually I convinced the judge to let me go on a Californian tour so I could make some money. MCA’s lawyers were telling him I couldn’t do it as I’d incur debts and I couldn’t show any security. So I said to the judge, ‘But judge, there is no security in rock’n’roll,’ and he laughed and let me do it.”

The resulting dates – the ‘Lawsuit Tour’ (also known to posterity as the ‘Why MCA? Tour’) – culminated in two sold-out shows in the Universal Amphitheatre, a large hall owned by, whom else, MCA. The executive director was one Danny Bramson, who intervened between artist and company and persuaded them to create the offshoot Backstreet Records (named after Bruce Springsteen’s song Backstreets) for Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers.

“They didn’t realise how serious I was. I sold everything I had to get what was rightfully ours. It saved the group morale-wise because I never believed that record would make it.”

But Torpedoes hits the target and goes double platinum. And after all, Tom is under the wing of the canniest Svengalis on the West Coast. He’s managed by Elliot Roberts (Joni Mitchell and Neil Young’s mentor since 1969) and his English partner, Tony Dimitriades, a former business manager/lawyer of The Kinks with ties to Claire Hamill. Such big hitters; MCA couldn’t be happier. Petty is their boy now (even if he is signed to a subsidiary label). He’s a 27-year-old whose first album has sold over one-and-a-half-million copies, and which will leave Cheap Trick, The Cars and The Knack in its wake.

Any advance warnings regarding Petty’s tempestuous personality seem far-fetched now, alone together in a room. He’s on the wagon for the duration, having had his tonsils removed three weeks earlier, a nasty goodbye to useless nodules when you’re 28.

In the US he’d thrown an almighty strop when shown his media schedule. “I fucked up a gig because I was out doing interviews,” he’d said. “All that talking cost me my fucking voice. That’s never going to happen again,” he told Dimitriades. “I should be all right for singing as long as I don’t have to do any fucking interviews in the next few days.”

In London, he feels more secure. “I came here a bit before doc’s orders,” Petty drawls pleasantly. “Hospitals are dreadful places. I had three months of a really painful throat. I couldn’t smoke cigarettes, have a joint, nothing. I haven’t been that clear-headed for years. Some of my closest friends say it improved my character a great deal.”

He chuckles and reaches for a Benson. “I can’t live like a boy scout. As Mark Twain said when they told him to give up cigarettes or die, ‘Life ain’t worth living without ’em.’” Close, but no cigar.

I ask Petty if he has taken stock from the aftermath of the new bands. He professes a liking for Devo “in doses” and The Clash’s London Calling in its entirety. His tastes are orthodox but his reasoning is honest.

“I’m out of touch, really. One of the bad things about this so-called success is if you go to see somebody, you can get bothered to the point where you don’t enjoy it… it’s an ordeal. I didn’t expect it to be quite as manic; people running after your car and crawling through your windows. It isn’t so bad; it’s what I always wanted, I guess. They don’t want to hurt you.

“But if I go to a club, there’s so many music company types, so many LA scene makers, they can spoil your private life. If I see a new band, I find it hard to be objectively involved: it’s impossible to go somewhere and make up your own mind.”

Generally he admits there is something in the air. “America’s come a long way. I’m proud. If I’m gonna wave the ole US banner, I admire Cheap Trick and Neil Young for being loonier than anyone else. The main thing is you can go to towns which were dead three years ago, places like St Louis, and there’re hundreds of new bands all writing their own songs and all finding some kind of audience.”

Petty shares Bruce Springsteen’s love for the romantic image and working-class sass. He’s smart enough to stay close to the street but not dumb enough to get stuck on it.

“Well, we were the first American band who weren’t punk who were doing that stuff, three-minute songs that weren’t mush. Now the first album doesn’t sound weird at all. I said a lot of things then that I regret – I was always shooting my mouth off. I was a big fan of a lot of that though, I’ve always supported the lunatic fringe because that’s where it’s all gonna come from. When we were here, people always approached us as punk and we’d say, ‘No, we’re a rock’n’roll band’. We didn’t fit that category. Then all we heard was punk this, punk that and we said, ‘Fuck punk!’

“We decided to let our hair grow till it’s down to here and they’re starting to call us punks in America. It was absurd, these stupid labels. That’s the time when they don’t even know what a punk is in America, and one day I just said to a guy, as a joke, ‘If you call me a punk again, I’m gonna cut ya.’ So now I get kids comin’ up and asking me why I’m so down on new wave and I have to tell ’em: ‘Fuck, I invented that new wave here for all you know.’ I’ve always wanted that cleared up ’cos of the animosity it caused. The truth is that I’m glad we were here in ’77. I used to laugh myself sick at the Sex Pistols’ antics. Every day you could buy a paper and there was something outrageous going on.”

Watching the gig in Hammersmith, it’s clear this is Petty’s show. “The others all have cliques of fans who come but I’d stand out if I was the bassist, being blond and all. I think they’re happy just to get the money. Benmont [Tench, keyboards] gets a much better shot on this album.

“We’ve always been cast in the twelve-string sound; those Byrds comparisons. I know we sound like them at times, and God knows I’ve tried not to, but I get a bit tired of hearing them now. I don’t think Roger McGuinn can do all the things people say he can. We’re entirely different musicians really. Of course, I’d be interested to see how he did Here Comes My Girl. But he phoned me last year to ask if I had any songs for him and I couldn’t come up with one that was suitable.”

One of the smartest things Petty ever did was to appear on the ‘No Nukes’ benefit on the same night as Springsteen. It was good for his credibility and it increased his drawing power on the East Coast.

“While we were in limbo with the lawsuits, I’d read in the Los Angeles Times about radiation creeping in. I’m not a very political guy but I’m getting worried. At least let the Russians bomb us – it would be so embarrassing to blow ourselves up.

“Mike [Campbell, guitarist] and I discussed playing one of those benefits because we thought we’d draw a completely different crowd to the people Jackson Browne and Graham Nash get, the Woodstock types. When Bruce phoned me to play with him – and he doesn’t usually have other groups on his bill – we decided to do it. We don’t preach or send out leaflets. I haven’t heard the album anyway – it doesn’t look very interesting. I saw the show and that was enough.

“I’ve changed my mind about a lot of things. I used to say, ‘Fuck the whales,’ but now I think we ought to save them too. Why not?”

It’s possible to view this softening process with some cynicism, as part of the homogenised image that tends to accompany stardom, but Petty had no guarantee that Damn The Torpedoes would catch fire.

“If those people had kept on suing me, I was going to be on a soup line. I’ve never got onto that channel about ‘what is life?’. This time I had a few sleepless nights. I wanted to write anthems for underdogs, songs like Even The Losers and Refugee. The theme of the album wasn’t self-conscious but when I put it together afterwards I could see it was about standing up for your rights, the ones that everyone has which can’t be fucked with or taken away. Rather than get really graphic – ‘They took me down to the court today and grilled me for eight hours’ – I wanted to keep the common denominator of them as love songs with other connotations.

“They aren’t necessarily boy-girl songs, but I don’t think the kids want to hear a record about the evils of the music business. That’d be boring as hell.

Meanwhile, he’s adept at accepting the plaudits while keeping one step ahead of the pundits. He takes his job seriously. He calls his songs ‘disposable’ yet he risked bankruptcy for them. He says of songwriting: “I refuse to think of it as work” – but his game plan looks like very hard work indeed. As for his philosophy, his attitude to the demands of the current lifestyle springs from an expression of naivety based on solid self-assurance.

“I’ve proved everything to myself. One of my favourite Dylan lines is, ‘I’ve got nothing to live up to,’ and that’s what I feel. I don’t have to prove it to anyone else.”

Part Two. July 1981. Los Angeles. Tom Petty is back in his adopted home and trying to adjust to two weeks off the treadmill. His new album Hard Promises is No.1 on the newly minted airwave-driven Billboard Rock Tracks chart but won’t eclipse Damn The Torpedoes. Yet again, he’s fallen out with MCA who want to charge record buyers $9.98 rather than the usual $8.98. Steely Dan don’t mind the extra dollar but Petty thinks they’re ripping the fans off and airs his disgust publicly. MCA back down after Petty threatens to call the album Eight Ninety-Eight – although the working title of Hard Promises is Benmont’s Revenge, a reference to keyboard player Benmont Tench’s mild accusation that he wasn’t given enough to do.

These are strange times for Petty. Success and fame are uneasy bedfellows and the Heartbreakers have fallen into the usual drugs and booze mess that goes with living in too many hotel rooms with too much money and nothing to spend it on. Bassist Ron Blair hated touring and was replaced on certain sessions by the veteran Donald ‘Duck’ Dunn (Blair would leave thereafter), while Petty had personal and professional problems.

His mother Kitty had passed away the day after his 30th birthday the previous October. Devastated as he was, Petty chose not to attend her funeral in his home town of Gainesville, Florida because he reasoned his presence would turn a sombre affair into a three-ring media circus. But he also had issues with his father Earl, who he would later admit had physically and mentally abused him as a child. When I spoke to him the day after the band had played three SRO concerts at th e 18,000-seater LA Forum, he mentioned this distressing episode but glossed over it.

“Mum and dad had a car wreck [after which Kitty became epileptic]. She was dying of cancer anyway. My dad’s disabled so he does nothing except play High Life all day. That’s a gambling game, big in Florida.

“I’d like my dad to see us play. He never has and we’ve never been back to Gainesville. But he has the fans come round and he chats to ’em and feeds ’em and stuff. He loves that.”

And the Heartbreakers will return to their Gatorland stomping ground that October, at the O’Connell Centre with Stevie Nicks as special guest.

The arrival of Nicks in Tom’s life proved fortunate. “She started hanging out at the Torpedoes sessions and asked me to write her a song. Me and Mike [Campbell] wrote Insider for her but I decided to keep that so we gave her Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around instead and she sang on my album and I’m producing her.”

In fact, Nicks’s Bella Donna disc will outstrip Promises, largely thanks to the heavy rotation of Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around on the then brand new MTV playlist. Petty didn’t know that then.

“I’m glad because finally the girl appears on the album and she’s happy because it’s a snaky thing and it ain’t a ballad. She told me, ‘Don’t give me another ballad. I write those all the time!’ So we’re doin’ a kind of Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris thing. Grievous Angel is in my all-time top five albums. Always wanted to meet Gram, but when I got to LA he’d been dead for four months. People always say, ‘Oh ,you’re like Roger McGuinn,’ but I prefer the Parsons’ Byrds. It’s hard to introduce country rock into what we do. People think it’s corny parents’ music but we’re southern country like Gram [who was from Georgia] and I still feel dislocated in LA.”

In San Francisco a week earlier, Petty, Nicks and her choir of girlfriends, including new bosom buddy Sharon Celani, Tench and Campbell persuaded the hotel piano bar to let them play a few songs. They knocked out Needles And Pins, His Latest Flame, Cathy’s Clown and the old Penguins doo-wop number Earth Angel. One of the businessmen at the bar gives them 10 bucks, which Petty pockets until Stevie grabs it off him after one of the businessman in the joint says, ‘That’s for the lady’.

“I said, ‘Hey, where’s my share?’ So Stevie rips the bill in half, sticks her half down her cleavage and gives me mine.”

Nicks will soon become a regular on Petty tours and is often heard admitting that she’d rather join the Heartbreakers than carry on with Fleetwood Mac. A glimpse into her superstar life proves salutary. There’s the feeling that Tom Petty is one step away from that rarefied world. His rival Bruce Springsteen is just of reach and Tom is forever playing catch-up. Springsteen is a year older and seemingly always one album ahead. Hard Promises goes platinum in 1981 but The River goes five times platinum. As I’d somewhat tactlessly pointed out in London, Springsteen can do no wrong with British critics. The sun shines from his fundament.

Maybe there was an element of a fit of pique when Petty pulled the band’s live performance off the No Nukes movie, and it must have galled him to support The Boss and Peter Tosh at Madison Square Garden. Six years later he’d sit down and write a song lampooning Springsteen called Tweeter And The Monkey Man with fellow Traveling Wilbury Bob Dylan, who was equally irked at hearing Springsteen referred to as his replacement: ‘The new Bob Dylan.’ They’d laughed as they wrote: ‘It was out on Thunder Road/Tweeter at the wheel/They crashed into paradise/They could hear them tires squeal,’ while George Harrison and Jeff Lynne looked on.

Back in real time, Petty had enough on his plate. The stream of fans camped outside his house forced him to hire security and he wrote Nightwatchman about his gate man. “Mike thinks it’s funny that I have a security guard ’cos we’re just as scummy as ever. Now I’ve got this guy directing traffic: ‘Just move on please.’ He [the nightwatchman] came to see us play last night and says, ‘Oh, so that’s what you do. Now I get why I have this job.’ But don’t make out I’m complaining. There aren’t so many kids any more. Maybe they got the message. Or maybe I’m fading out,” he laughs.

Petty admits, “I was in a strange state of mind when I wrote this album. It’s been like an exorcism. Why Hard Promises? Well, anything that’s worth working for is a hard promise to me. I put a lyric sheet in for the first time because it’s the first time the words were good enough to be printed. Funny thing is no one ever mentioned the lyrics until I did that, probably couldn’t understand a word I sang. Personally, I don’t have much time for lyric sheets. I don’t want to be reading when I’m listening.”

The night before, there’d been a riot and a stage invasion at the Forum that infuriated Petty. He stomped off afterwards and refused to attend the obligatory après-gig party. “I was in a bad mood anyway ’cos I know how much the people at the front paid the scalpers and I wouldn’t want to be pushed out my seat. We played in New York recently and a lot of kids got seriously mashed and taken to hospital, but that was at a festival.”

His biggest problem, he says, is, “I can’t unwind. I haven’t been to bed for three days. I don’t take sleeping pills any more – they put me in such a lousy mood – and other drugs don’t work. I’m so charged up by playing a big room, by the energy – sorry to be Californian – but it’s like you get zapped. I’m on an insane schedule.”

On the plus side, his six-year-old daughter Adria gets to see him perform for the first time at the Forum, holding Stevie Nicks’s hand tight in the wings. “On the way home she says to me, ‘Why didn’t you call me out?’ I’m like, ‘To do what exactly?’ She wasn’t fazed one bit,” Petty sighs. “I haven’t spent enough time with her.”

Nor will he, as the Heartbreakers gang rolls across America. “Thing is, if we ain’t playing, we all get bored so easy. I can’t switch off. I’m getting a little tired of recording in Los Angeles, tell you the truth. I want to record the next album in Memphis.”

A solo album? “Nah, why the hell would I do that? I’d end up using the Heartbreakers anyway. It’s just time for us to go back to our roots. We’ve exhausted this place.”

Tape recorder turned off, Petty pours a cup of tea and gets up to go. “Me and Mike have a song we’re working out called Gator On The Lawn. It’s a B-side but I want to play it live when we hit the road.”

You can take the man out of the south, but you can’t take the south out of the man.

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 202, September 2014