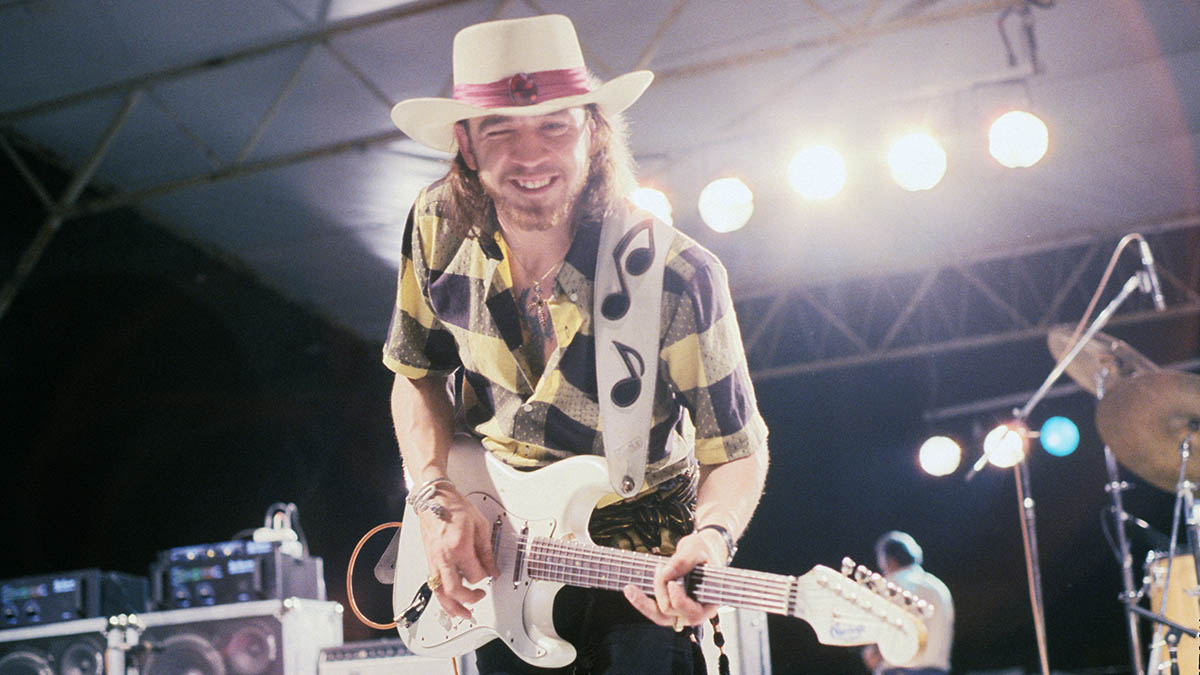

Many artists would have struggled to follow a debut album as game-changing as Texas Flood. Not SRV, however, who showed no signs of second album syndrome on 1984’s Couldn’t Stand The Weather.

Its opening track, the fiery instrumental he named Scuttle Buttin’, is arguably the most technically demanding piece of music he ever put his name to.

An uptempo 12-bar shuffle delivered in fast and furious style in under two minutes, in which he ripped through the open position of the Eb blues scale at 162bpm, demonstrating his ferocious alternate-picking skills with flickers of legato and glissando to round it all off. But it was far greater than an exercise in clinical repetition, instead typifying a gift most natural indeed – the kind very few are born with.

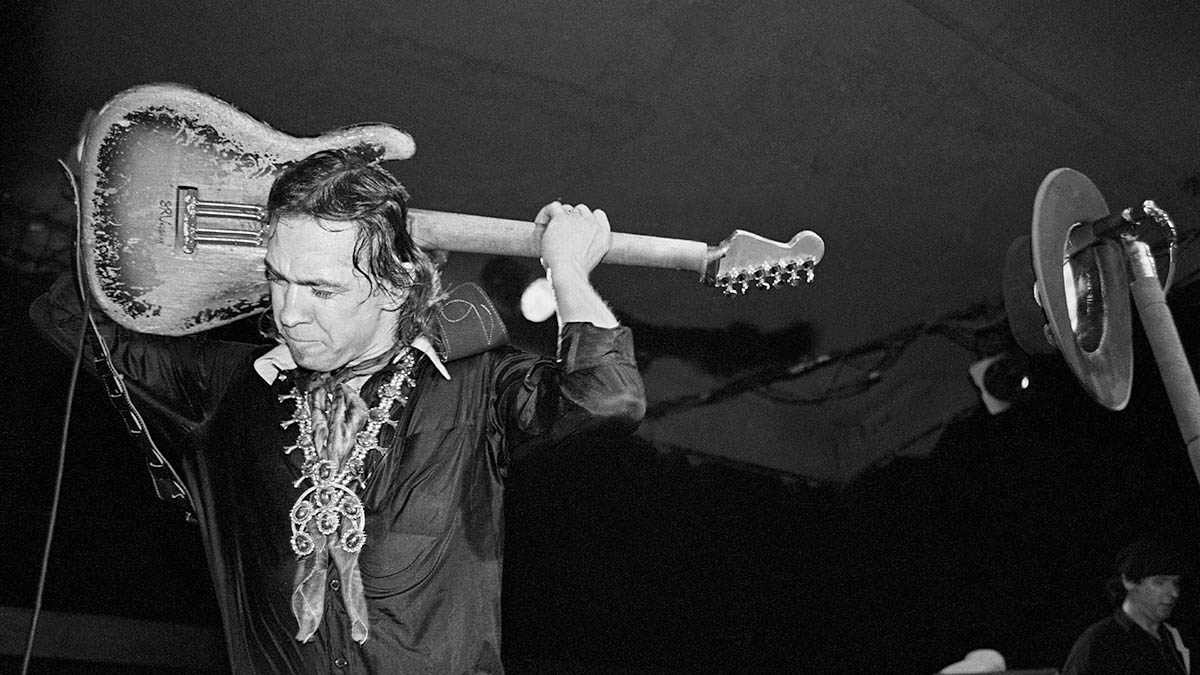

The title track from Couldn’t Stand The Weather was issued as a single with a video that received regular rotation on MTV. In this, Stevie can be seen playing his Hamiltone Stratocaster copy built by New York luthier James Hamilton. It had been commissioned by ZZ Top legend Billy Gibbons, and was presented to SRV as a gift on April 29, 1984.

Though it was similar in shape, the guitar carried a few notable differences to the real-deal Strats the guitarist was usually seen with, such as the neck-through-body design instead of the standard Fender bolt-on, and a two-piece maple body as opposed to his favoured alder.

In place of the usual rosewood, the fretboard was made out of ebony featured an abalone inlay emblazoned with the guitarist’s name. Somewhat ironically, during the video shoot the guitar itself couldn’t stand the weather, with the EMG pickups damaged by the ‘rain’ falling on the musicians and their instruments. Stevie replaced them with stock Fender single coils.

Other highlights from the album included slow blues Tin Pan Alley, jazz closer Stang’s Swang and W.C. Clark/Mike Kindred cover Cold Shot – which, like title track, made use of the Fender Vibratone cabinet manufactured by the American guitar company during the late-’60s and early-’70s.

A modulation effect would be produced by its 10-inch speaker and cylinder being mechanically rotated by a motor with a rubber belt, taking advantage of the Doppler effect – which is the apparent change in frequency of a wave to the listener as a result of motion.

Soul to Soul, the third album by Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble, arrived in 1985, and again yielded some staggeringly thrilling and ambitious moments as the band dared to tread new ground with keyboardist Reese Wynans, who now plays with Joe Bonamassa.

Look At Little Sister, for example, drifted away from their roots as a power trio and incorporated some honky-tonk piano as well as a saxophone solo, whereas Change It felt like a heavier and more modern take on the traditional blues format pursued on their earlier recordings. And on the closing ballad Life Without You he sang as beautifully as he played – a masterclass in sonic perfection.

As drummer Chris Layton recalls: “I guess to some extent we all had that perfectionist ideal, always wanting to get a little better, but Stevie was a really easy-going guy. He was a very forgiving person, and generous.

“The one thing he was demanding of – without ever saying it – was trying our hardest and being the best we could be. It was never like, ‘Uh oh, you made a mistake!’ In fact, he’d often say a mistake might even be something new – let’s go with it and see where it takes us instead of stopping and starting again because it was played wrong.

We never really analysed what we were doing. We just had to put our hearts and souls into what we were playing

Chris Layton

“That was a beautiful thing about him. We never really analysed what we were doing. We just had to put our hearts and souls into what we were playing. There were no qualifications, rules or regulations, which was cool but also kinda daunting – especially when you’re on stage in front of 20,000 people and he starts playing something new! You have to jump in and not question whether it will work or not. We just had to take off and try our best!”

It was in this period that Stevie’s alcohol and cocaine addictions began to spiral out of control, almost killing him from dehydration in Germany and famously leading to a blackout on stage in London. As he later revealed: “I would wake up and guzzle something just to get rid of the pain I was feeling. It was like… solid doom.”

After doctors warned him that he was just months away from death, Stevie entered rehab in 1986 and continued his recovery after relocating back to the house he grew up in. Although he was nervous about performing sober, he returned to the stage on November 23 of that year at Maryland’s Towson State University.

Sadly, as fate would have it, the 1989 album In Step – its title openly referring to his recent experience of rehabilitation – would end up being the final release from Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble.

It remains a favourite among fans for many reasons, with the quartet broadening their horizons and penning tracks that felt slicker and ultimately bigger than their earlier work, with additional horns, saxophones and trumpets for good measure.

Opening track The House Is Rockin’ includes some phenomenal interplay between SRV and Wynans, and a new sense of musical focus is evident.

There’s the band boogie of Crossfire, and the funky shuffle of Tightrope features another example of Stevie’s dynamic phrasing during the solo section, where he leaves long gaps in between his musical sentences to let the conversation flow naturally. And, just like everything they’d recorded thus far, there were many different shades of blue to be found in between its energetic opener, the slower 1-4-5 of Leave My Girl Alone and grand finale Riviera Paradise.

Says Chris Layton: “All the stuff we recorded together, from Tightrope, Lookin’ Out The Window and Leave My Girl Alone to Crossfire to Riviera Paradise and Stang’s Swang, these were all incredible songs and all very different. It wasn’t just the blues format dragging on and on.”

To promote In Step, the band joined forces on a tour with Jeff Beck and his group, who had recently released the highly acclaimed Jeff Beck’s Guitar Shop album. Anyone who was lucky enough to catch any of the 29 dates on The Fire Meets the Fury Tour will have seen two of greatest guitar players of all time going head-to-head on latter-day releases that proved they still had plenty to say. But, of course, in SRV’s case, it was just not meant to be.

During one month in 1990 he had teamed up with big brother Jimmie to record the album Family Style, credited to The Vaughan Brothers. The album was produced by Nile Rodgers, and for a lot of those recordings Stevie ended up using the Chic guitarist’s black Strat with gold hardware.

“He loved the way it sounded,” Rodgers told Total Guitar. “A few months before doing that Vaughan Brothers record, I went out and bought that guitar from Manny’s in New York. I might actually send that to Fender and have them come up with the story of how it was made and why it was made that year… because it was not a normal kind of Strat.”

On August 27 of that year, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble played as support act to Eric Clapton at the Alpine Valley Music Theater in Wisconsin. The show climaxed with an all-star jam. Shortly after, Stevie joined three members of Clapton’s entourage in a helicopter bound for Chicago. In foggy conditions, the helicopter crashed half a mile from its take-off point, killing all onboard.

As Chris Layton solemnly recalls, “The night he died, we spoke for an hour about what was next. Stevie said that he and Jimmie were going to do some stuff to promote the Family Style record, and then he said, ‘I’m really excited because once we’re done with that, I’ve got a bunch of ideas that, I hope I don’t freak you out – but I’m hearing strings and brass and a whole different bunch of shit compared to what we’ve done in the past!’

“He was really jazzed about it and wanted us to be, too. These were just ideas pouring out of him and I couldn’t wait to hear them. Then he got on that helicopter and took off. I think that’s the best insight of knowing where he was going… and the future that never happened.”

Chris has so many great memories from the years he spent with Stevie. What he remembers most of all is a man who lived for playing guitar. “Stevie had a guitar in his hand most of the time,” he says. “He’d always be sat there playing away, but not rehearsing or anything. He was just always strumming that guitar. That’s what was amazingly pure about him. Playing guitar was his life.”