Paralyzed by its most radical members, the House of Representatives passed just 27 bills that became law in 2023 — down nearly 90% from the previous year. Republicans who see big government as a threat to liberty view this failure as a “success.”

The idea of small government, however, is a myth at odds with U.S. history. In our new book, “How Government Built America,” we explore the extent to which the U.S. government has intervened in markets since the Colonial era. It turns out the country has always had big government.

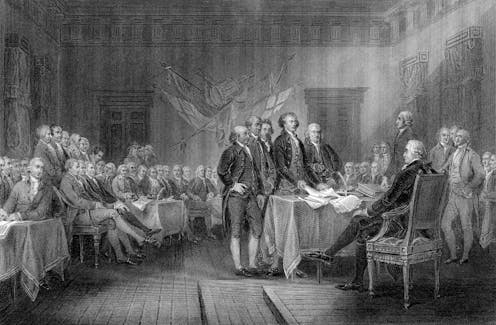

Big government, 18th-century style

Small-government advocates claim that the idea of limited government is foundational to the United States. But the Founding Fathers – including the ones who appear on today’s US$1 and $10 bills – called for the new government to intervene in markets.

Consider the situation in the late 18th century. After the U.S. won independence from Great Britain, two political groups – the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists – struggled to divide power between the federal and state governments.

While the Federalists favored a strong national government – which the Anti-Federalists opposed – both sides agreed that government should have a substantial role in the new nation. The Anti-Federalists weren’t opposed to strong government, but they wanted to keep it at the local level.

The Federalists, including Alexander Hamilton, George Washington and John Adams, won out. They led the federal government’s efforts to manage the economy and invest in infrastructure, including the building of canals, bridges and roads. To this day, the federal government makes similar investments to promote prosperity.

Thomas Jefferson and other Anti-Federalists did believe that a powerful centralized federal government was more likely to be corrupted than if government were kept local. In his inaugural address, Jefferson called for “a wise and frugal Government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement.”

But Jefferson didn’t campaign against the widespread regulatory activities that were taking place at the state level. At the time, almost every aspect of early American economy and society, from Sunday observance to the operation of taverns, was regulated by the states, and, before them, the colonies. This was “big” government.

Jefferson, like other founders, was influenced by a political philosophy, republicanism – not to be confused with today’s Republican Party – which understands the furtherance of the public good as a key goal of good government. These lowercase republicans put the government in charge of organizing economic and social activity.

Some of that government, Jefferson conceded, had to be at a national level. As president, he supported key elements of the national government established by the Federalists, including the national bank.

Three centuries of big government

A similar pattern has played out throughout American history. Markets produced an Industrial Revolution during the 1800s, but they also introduced dangerous workplaces, products, slums and poverty, which restricted individual opportunity and threatened people’s lives. The federal government responded by taking over from the states, for the first time, the function of regulating consumer markets, including railroad regulation, antitrust enforcement and food and drug safety.

And when market freedom led to the Great Depression of 1929-1939, it was government that restored economic opportunity and helped people to live and work in the meantime.

More recently, when Wall Street crashed the economy in the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, government had to act again to restore markets. When COVID-19 hit, government hastened the development of vaccines and thus the restoration of people’s freedom to live and work.

A question of values

We believe the myth of small government not only goes against the realities of American history, but it also threatens the basic political values of the country. It has taken both markets and government to build a country truer to American values of liberty, equality, fairness and the common good.

Take liberty, for example. Markets are celebrated for promoting individual liberty when individuals purchase a car, start a business and make countless other market decisions. According to this understanding, market participants are free to make their own choices, and as they do so, markets build wealth and prosperity for the country.

The internet revolution is a good example. Consumers have endless choices of programming, software, podcasts and other social media as entrepreneurs seek their attention and business.

But as history shows, markets can also limit the liberty of consumers and workers, and when this happens, the public interest is not served. Consider how the internet can threaten the safety and well-being of children.

The U.S. can shrink its government, as its most determined political opponents demand, but history shows that the dangers markets pose will not go away. For example, the world is facing the “existential threat” of climate change – a problem that can’t be solved with free markets alone.

The exact mix of government and markets has been contested throughout American history, and preference for “small” government is a perennial campaign theme. But the idea that the country is best served by “big markets” unsupervised by “big” government, as far-right House members insist, ignores centuries of American history.

Sidney Shapiro is affiliated with the Center for Progressive Reform

Joseph P. Tomain does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.