Virgin Orbit, a US company which provides launch services for satellites, has announced that the first orbital space mission from the UK will blast off from Cornwall. The rocket, which will carry nine satellites, along with a launch aircraft have been delivered by an RAF C-17 – a military, heavy-lift strategic transport plane.

This is primed to be a new phase for the UK and its involvement in space missions. It has the potential to bring tourism, economic benefits and jobs to the country. But is it a practical launch site and could we expect the likes of SpaceX or Nasa to book it in the future?

First of all, it is important to note that Virgin Orbit should not be confused with Virgin Galactic. Virgin Orbit is for commercial customers wishing to launch small satellites (including the first Welsh satellite) into orbit. Virgin Galactic, on the other hand, is an ego boosting mission to send wealthy people high in the atmosphere for a few minutes of free-fall.

Secondly, if you are in Cornwall expecting a Cape-Canaveral type scene with plumes of smoke pouring towards you, then you may need to lower your expectations. This will be a “horizontal launch”, meaning the rocket will be strapped under the wing of a plane and taken up to 10km (35,000 feet) before the full engines fire.

The rocket will be attached to the wing of Cosmic Girl, a Boeing 747-400 which has been converted from a passenger aircraft. You may think that the speed of the aircraft helps give the rocket a boost. But the average cruising speed of a 747-400 is roughly 900km per hour, which is roughly 0.25km per second. That is fast, but won’t make much of an impact on the roughly 9km per second needed to launch from the surface into Low Earth Orbit.

The major benefit of launching from a plane is in fact the increase in altitude rather than speed. As you climb, the air gets thinner – at 10km the air density is 0.4 kg/m3, roughly a third of the density at sea level. This significantly reduces drag on the rocket during its ascent and hence improves fuel efficiency. It is also worth noting that the smaller range of pressure changes that the rocket engine has to deal with while it is burning fuel also improves efficiency.

Of course the idea of launching something from an aircraft is hardly a new idea. Planes launched from larger planes (known as parasite fighters) have been around for over 100 years. And in 1990, the company today known as Northrop Grumman launched the first ever rocket from an aircraft. There are even companies which now launch from weather balloons.

Why the UK?

The bigger question of course is why the launch is happening from Cornwall. As a provider of space research, the UK has been a big player, yet has never had its own space programme. The preference for a space launch location has been part of the UK space agency plan to hold a 10% share of the space market by 2030.

There have long been rumours that the UK might get a remote Scottish spaceport. This would be advantageous as space launch locations are required to have a number of fundamental properties. It is ideal to launch eastwards as the rotation of the Earth is about 0.45 km per second near the equator, which helps with reaching orbit. And you need a vast expanse of ocean or empty land to ensure that if your rocket fails, you are not causing a loss of life.

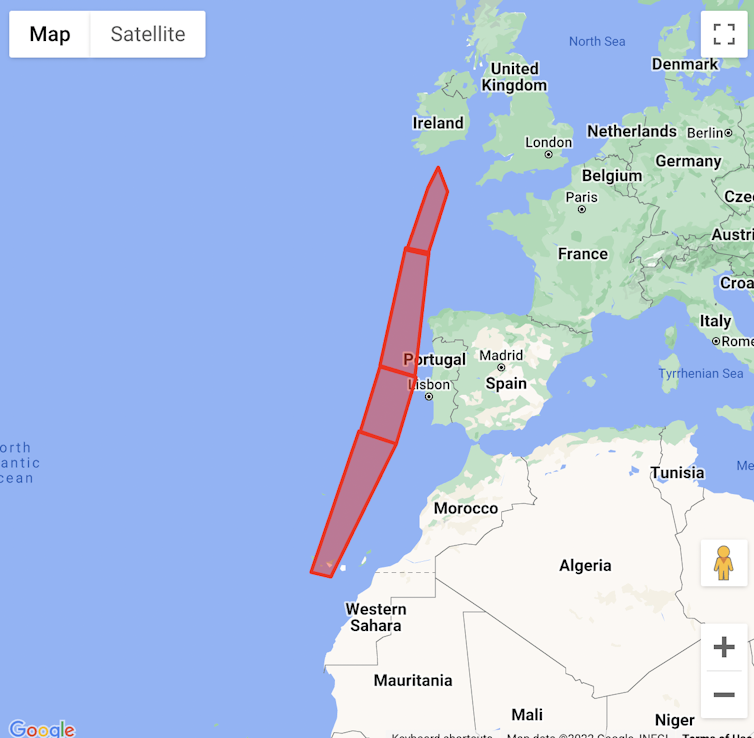

Cornwall has neither of these properties. At 50 degrees latitude, far north of the equator, the Cosmic Girl launch will be south westerly. This means it will have to partially fight the rotation of the Earth to reach a standard orbit.

Any launches from this facility in the future have to be via plane, as an eastward launch directly from the ground risks crashing into the south coast of England, France, or even Belgium. For a polar orbit (circling roughly from pole to pole rather than around the equator), however, the site might be more viable, although would still require launching from a higher elevation.

The current payload for this mission is a number of commercial and government satellites. Compared to scientific launches, there is limited information on the mission. From what is known about the satellites they are likely to be in an inclined orbit (around the equator).

Perhaps just as important is the fortuitous timing. Virgin Orbit decided to go for the launch just as the pound dropped in power against the dollar. While Virgin Orbit has been planning to use the Cornwall base for months, it definitely benefits them to go for it at this specific moment.

Future plans

This may also benefit the UK too, as there is the hope that more space missions will now have the UK involved. It is no secret that since the UK has left the EU, the involvement of UK scientists in international space projects, facilities and funding bids, such as through the EU programme “Horizon 2020”, have dropped considerably.

So as well as Cornwall, the Saxavord spaceport in the Shetland islands is scheduled for construction soon. Whether this actually gets built is another question. An alternative spaceport on the A'Mhoine peninsular in Scotland was scheduled for building in 2018 with the first launch last year, yet it has still has not been built. The effect on the local wildlife in both cases might cause further delays or even abandonment.

While we have no idea how popular the Cornwall Spaceport will be in terms of external partners, it will be of huge value to schools and universities in the country. Seeing commercial business using UK facilities and being able to visit the locations will be a much needed boost for most STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) subjects.

But given that Cornwall lacks many of the properties needed for efficient launches, we are probably only likely to see some small commercial launches from there. The hope of being able to see astronauts take off from the UK is, unfortunately, an exceptionally long way off.

Ian Whittaker does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.