Over the half-century we’ve had the pleasure of his company, David Gilmour has never been one for hype or hot air.

While other rock stars deliver each new album alongside chest-beating proclamations of its greatness, the former Pink Floyd legend has always let his exquisite phrasing do the talking (a marketing non-strategy that has nonetheless gifted him career album sales north of 250 million).

Given his reticence for the hard sell, the opinion that Gilmour voices in the making-of video for new solo record Luck and Strange is liable to stop you in your tracks. “This is the best work I’ve done, and the best album I’ve made,” considers the 78-year-old in the final frame, “since The Dark Side of the Moon in 1973.”

At first glance, it’s an outrageous statement. Better than Floyd’s 1975 opus Wish You Were Here, home to the haunting four-note starburst of Shine On You Crazy Diamond? Better than 1979’s biting double-album polemic The Wall, whose aching Comfortably Numb solo is so perfect you’re scared to breathe while it plays?

But when Guitar World negotiates a rare interview with Gilmour – whose long stewardship of Pink Floyd ended with 2014’s swansong The Endless River – the guitarist doubles down. And the curious thing is, the longer you live with Luck and Strange, the more you come around to his way of thinking. Bewitching and wistful, with melodies that punch through like sunbeams, these songs of love and mortality are decorated by some of Gilmour’s most stunning touches and emotive playing.

“I genuinely think it’s as good as anything I’ve ever done,” says the guitarist, speaking from Astoria, the houseboat-slash-studio that has been his creative nerve center since 1986. “I’ve been able to throw away the rulebook on anything I might have to adhere to with people’s expectations.”

Luck and Strange sounds like a real family affair. Your wife Polly Samson once again wrote lyrics, while your daughter Romany sang and played harp.

“This album is something that really came out of Covid. We were locked down together, and the topics of discussion were the dangers of the virus and how many ancient old people like me were going to get killed off in the first flush. And of course, Polly’s novel [A Theatre for Dreamers] was released in the first week of lockdown, so we couldn’t do the shows we were planning to promote it.

The chains of the past were blasted asunder. I’m genuinely thrilled with this album

“Charlie, our son, said, ‘Just do a livestream.’ So we filmed it from our barn, with Polly reading from her book, answering questions from people online – and playing a couple of songs. And ‘playing a couple of songs’ very quickly became me and Romany playing and singing songs together.

“All of that experience gave me a feeling that I could be freer than I had been, than I’d allowed myself to be. There was that feeling of, ‘Fuck it, I’ll do exactly what I feel like doing, with whoever I fucking feel like doing it with.’ There was a release in that. You know, the chains of the past were blasted asunder. I’m genuinely thrilled with this album.”

Recruiting Alt-J producer Charlie Andrew was an interesting move. It sounds like he wasn’t overawed by your reputation and really challenged you. Is it important not to surround yourself with “yes” men?

“That is a big danger. You want true, honest opinions that are freely stated. You want to be freed up to do whatever you feel like doing. And having any weight of expectation of what’s gone before clouding the vision of your collaborators is something you want to avoid. I guess someone who comes with the baggage, if you like, that I come with, it’s going to be a bit intimidating to many people. But Charlie didn’t show any sign of being intimidated.”

Charlie asked us, ‘Why is there a guitar solo here?’ and ‘Why do they all fade out?’ There were these little moments that made us giggle

The story goes that when you met Charlie and played him the demos, he questioned some of the guitar solos.

“Yes. He asked us, ‘Why is there a guitar solo here?’ and ‘Why do they all fade out?’ There were these little moments that made us giggle. He also had very clear ideas about how we should approach the songs and the recording. That’s a great thing. You want things to be clear. I had not much in the way of problems with it.

“There was one song – A Single Spark – which took a bit of getting used to his approach. But I fell in love with it pretty quickly. And I think he developed a keenness on guitar solos he hadn’t previously had. I think he changed as much as I did. I think we both changed in our attitudes through the process.”

One of the most powerful moments is the title track, which grew from a jam with your late Pink Floyd bandmate, Rick Wright. What are your memories?

“Well, at the end of the On an Island tour, I thought the band was on fire. So I got them all to convene at my house, in the barn, in January 2007. To just throw ideas about, to muck about. I had lots of little semi-ideas that I wanted to try. So we went into the barn on the first morning.

“It was fucking freezing. It’s a rickety old barn. Big holes between the planks, the wind howling through, snowing outside. Really bitterly cold. I chose the timing very poorly. But I started playing that little lick that I had from somewhere. They all joined in and we jammed on it for 15 minutes.

“Of course, later, I had to split it up and write bridges and choruses – but that is the take you hear on the album. That’s what we used. It had never been played before. It had never been rehearsed. It just is what it is.”

What emotions came over you while working on that track and hearing Rick’s keys for the first time since his death in 2008? Joy, sorrow, nostalgia?

“All of those things, all the time. I mean, obviously, most of the time when you’re working, you’re focusing on what you have to do. I didn’t spend the whole time sitting around weeping. But Rick has a very unusual, idiosyncratic style that comes out in the track. It’s lovely.”

Your guitar is so atmospheric on the cover of the Montgolfier Brothers’ Between Two Points. It sounds like you were really channeling something.

“On the guitar solo? Yeah. It’s a song Polly and I have loved for years. I’d put together a rough backing track, Romany had done her vocal, and I played the guitar over it at the end. How does one describe it?

“I got so into the guitar part, it was like being on drugs. I could forget where I was in the moment and get completely lost in the playing. Which is actually quite unusual. It’s a feeling – a movement – that you search for. Because you always want to be completely lost in what you’re doing. But in my biased view, it really happened on that occasion.”

The solo on The Piper’s Call has a very contrasting feel. What was the inspiration there?

“It’s hard to pinpoint what inspires guitar parts. Things just demand to be done a certain way. No one is commanding you. That solo – that’s just how it came out. It’s the way it had to be. I had a clear idea of how The Piper’s Call should be, starting with just the groove chugging along, then this rough, raunchy sort of guitar solo. I wish I could be a bit more lucid and articulate. But it is what it is. It’s a moment.”

Another highlight is the call-and-response between multiple guitars on Scattered.

“That was great fun to record. There’s three guitar solos on that – one is on a nylon-string, then one on a Strat with a semi-beefy setting, then switching to the full Big Muff tone on that third one. It’s not that these guitar parts aren’t carefully thought out. But these ideas throw themselves at you and demand to be followed.”

Where did you choose to lay down these tracks?

“Well, there were a number of studios involved in this album. I have my own studio in Brighton [Medina], and we did a lot of the guitars and vocals there. We used a studio called Salvation Music Studios, which is an old ex-Salvation Army hall. We also used Mark Knopfler’s beautiful studio in West London, British Grove.

“I did a lot of it at home, in our barn studio, which works really well. There’s another one in North London called Angel Studios where we did orchestras and choirs. We recorded in a cathedral.

“A lot of it was down to Charlie Andrew saying, ‘I’d like to try this place…’ He and his fantastic engineer, Matt Glasbey, have all sorts of ideas about how they want things to sound – and they use 20 mics where I would use one. There were Pro Tools sessions that were way beyond my comprehension. But they find new ways of giving me a life and an air that we’re all after.”

What was it like working your guitar parts into Will Gardner’s string arrangements?

“Most of the guitars were done pre the orchestration. But Will Gardner is a genius. He’s off the wall. He goes places it wouldn’t occur to me to go. And it’s so great to have people around you who are inspiring and inspired. He did brilliant, brilliant, weird things. I mean, not all of it is weird. And the ‘weird’ is only there because that’s what works.”

The guitars have served me very well. They’ve done their job, they’re the tools of my trade. And the secret is you can always buy another one

It’s been five years since you auctioned the bulk of your guitar collection, including fabled Pink Floyd gear like the Black Strat. How do you feel about that decision now?

“The charity the money went to, ClientEarth, is doing the most extraordinary work throughout the world. Every day – I got one this morning – there’s an email about a court case they’ve won somewhere in the world, against countries where they break their own laws on climate change and emissions, or against people who are building plastics factories or cutting down medieval forests in Poland.

“ClientEarth brings a ton of heavy lawyers down on them, and they win these cases. I don’t think my money could have gone to a better place. The guitars have served me very well. They’ve done their job, they’re the tools of my trade. And the secret is [whispers conspiratorially], you can always buy another one.”

Was handing over the Black Strat like losing a limb – or was it actually liberating to cut the ties with your past?

“I mean, Fender did a David Gilmour model [launched in 2008], so now I’ve got the Black Cat Strat. And it’s the same, you know? It does what it says on the tin.”

But Floyd fans might argue there was an intangible magic in the original Black Strat. Can the same be said for the signature models?

“Phil Taylor, my guitar tech, insisted on a lot of affection from Fender before we’d agree to do it, and the David Gilmour Signature Strat is a fine, fine instrument. And we make sure it stays that way. We’re on their case about it regularly. I think they’ve done an extremely good job in making a beautiful guitar.”

Would it pass a blindfolded comparison with the original?

“It certainly would with me. Why wouldn’t it?”

A few guitars escaped that 2019 auction. Your 1950s Gretsch 6128 Duo Jet, for one.

“Yes. That one’s on Luck and Strange, the track itself. This is one of the guitars I have a genuine affection for and didn’t want to sell. I mean, it’s not like it’s the rarest guitar in the world and you couldn’t get another one. But I don’t want to appear too disparaging of the magic values of these tools of the trade.

“There are one or two I kept. There’s the old beat-up Telecaster [’55 Esquire]. And there were also a couple of other guitars I’d forgotten about, which were away in the Pink Floyd Exhibition [Their Mortal Remains] somewhere. Suddenly, they turned up and I said, ‘Fuck, I thought I’d sold all those!’”

How much action did those survivors see on this new album?

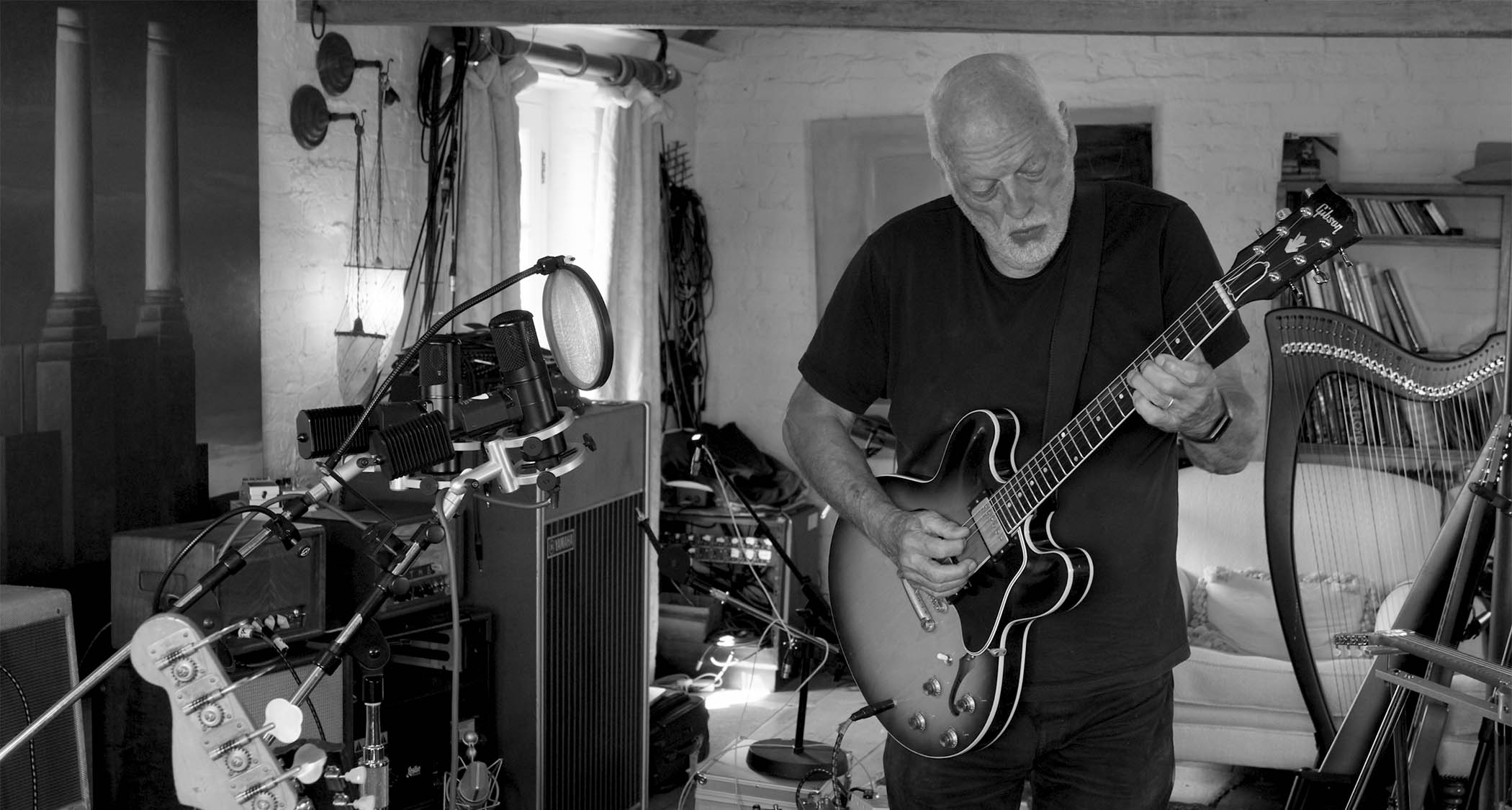

“Well, the Black Cat Strat – a lot. The Telecaster, a bit. Certainly, the Duo Jet is there on two or three tracks and is the main one on Luck and Strange. I’ve got a Gibson ES-335 I bought not so long ago; that’s on one track at least. And a Gibson goldtop, which is not the ’55 goldtop I used on Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2, because I sold that. But this was the spare. It’s the same year; it’s identical.”

Is your cherished 1945 Martin D-18 the acoustic guitar used on Yes, I Have Ghosts?

“I honestly can’t remember. It’s my favorite acoustic, and I wasn’t going to sell that one. But Martin have very kindly made me some new guitars as well. So I tried my best to get rid of some guitars… but I still seem to have quite a few.”

You’ve always had eclectic tastes, but one constant is that you love old gear. Some would argue that production methods get better over time with most things. Is that not true of guitars?

“I honestly believe you could pick up a 1954 Fender Stratocaster – from the first year they were made – and I can’t see how it could be improved. There’s a little fantasy-belief I hold, which is that when a guitar has been played for years, the vibrations of all the different bits of the body achieve some sort of harmony. So I think a 30-year-old Martin – identical to a new one – would definitely sound better.”

You once said the Stratocaster enhances the personality of the person playing it.

“The Stratocaster, I have believed for years, is a clearer signal for the person who’s playing it. The person who’s playing it is more recognizable on a Strat than, for example, on a Les Paul. That’s just another of my fantasy-beliefs.”

These days it seems fewer and fewer guitarists are using physical amps. How has your own philosophy changed since the days of your classic Hiwatt rig?

“Oh, I will be using physical heads and cabinets on the tour – but at home I have this thing that’s now 30 years old, called a Zoom. It’s a tiny little gray box, and I use that most of the time when I’m working on the early version of songs. Because I know how to work it, it’s got lots of good sounds and I know how to adjust them.”

You even wrote The Piper’s Call on a ukulele. How did that come about?

“I’ve got a 1950s Martin ukulele. It’s a lovely little thing. One day, it was sitting there, and I picked it up and strummed it, and found an unusual chord change I’ve never found before. One finger stays in one position, another finger moves from the second fret of the first string to the second fret of the third string. And that’s all it is. It’s the simplest thing.

“The whole song formed itself out of those two little notes. A bit like Shine On You Crazy Diamond formed itself out of those four little notes. These magic moments just pop out of their own volition.”

Do you have to be in a certain mood or mindset to lay down your solos?

“That’s a tough one. At the moment that I want to do that bit of playing, I obviously want to get myself into the right space. What else could I do? But I don’t have a formula or routine that I follow, or some particular exercises. I just play it and hope that my fingers and my brain and the instrument will be in some sort of harmony.”

With this album, there’s a real sense that you want to keep pushing the limits and creating new music. That you’re not satisfied to just play the hits?

“Yeah, absolutely. I’m much more interested in being part of the future than playing too much of the really old stuff. I mean, on the tour, I’m not going to not play any of the expected stuff. But the focus will be much more on recent times.”

You’ve said it was never your plan to become a solo artist.

“I started out when I was 16 in a band in my hometown of Cambridge. I like being a part of that setup. I never wanted to be a solo artist. When I joined Pink Floyd, same thing: I was very happy to be a part of something. And I got thrust into the role of leader.

“And that’s OK. That’s fine. I’m a big boy, I can cope. And I dealt with that as well as I could. But then, outside of that, it’s either forming another band or becoming a solo artist. And I really wouldn’t know where to start, forming a new band. That moment of being in a band – when you’re young, when you can shout at each other and fall out, but still be back at it, because your common destiny is still there… [Sighs] Yeah, I’m set in my ways now. It would be harder to do that today. It’s harder to be equal.”

You’ve made records amidst friction and tension – and you’ve also made records in the ethos of complete harmony, like this one. Which state do you find more productive?

“Oh, being in a state of harmony. But you might have different ideas about [the conflict in Pink Floyd]. There are publicly presumed, accepted versions of things which are not necessarily the way they were. Even some of the moments that felt like they had been pretty dark, the satisfaction of some of the musical achievements at the time were also great. So it’s not quite as simple as that.”

Finally, famous guitarists always say they’re trying to play more like David Gilmour as they mature. How has your own playing evolved since the ’70s?

[Deadpan] “I just try to play more like David Gilmour.”

- Luck and Strange is out now via Legacy.