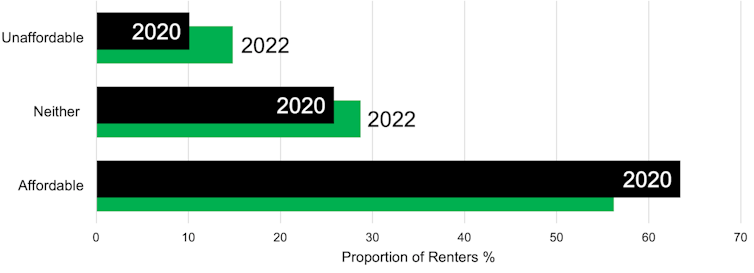

Roughly one in three Australians rent their homes. It’s Australia’s fastest-growing tenure, but renting is increasingly unaffordable. From 2020 to 2022, our research found a large increase in the proportion of renters who said their housing was unaffordable.

Australians are concerned about the pace of rent rises. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese says increasing housing supply and affordability is the “key priority” for tomorrow’s national cabinet meeting.

The crisis has impacts well beyond affordability. The rental sector is where the worst housing accommodates the poorest Australians with the worst health.

Read more: Ageing in a housing crisis: growing numbers of older Australians are facing a bleak future

The unhealthy state of rental housing

Forthcoming data from the Australian Housing Conditions Dataset highlight some of these parallel challenges:

it’s often insecure – the average lease is less than 12 months, and less than a third of formal rental agreements extend beyond 12 months

rental housing quality is often very poor – 45% of renters rate the condition of their dwelling as “average, poor, or very poor”

poor housing conditions put the health of renters at risk – 43% report problems with damp or mould, and 35% have difficulty keeping their homes warm in winter or cool in summer

compounding these health risks, people with poorer health are over-represented in the rental sector. Renters are almost twice as likely as mortgage holders to have poorer general health.

Measures that potentially restrict the supply of lower-cost rental housing – such as rent caps – will worsen these impacts. More households will be left searching in a shrinking pool of affordable housing.

Read more: 'It's soul-destroying': how people on a housing wait list of 175,000 describe their years of waiting

It’s all about supply

Fixing the rental crisis needs more than a single focus on private rental housing. The movement between households over time between renting and buying homes means the best solutions are those that boost the supply of affordable housing generally. No one policy can provide all the answers.

Governments should be looking at multiple actions, including:

requiring local councils to adopt affordable housing strategies as well as mandating inclusionary zoning, which requires developments to include a proportion of affordable homes

improving land supply through better forecasting at the national, state and local levels

giving housing and planning ministers the power to deliver affordable housing targets by providing support for demonstration projects, subsidised land to social housing providers and access to surplus land

boosting the recruitment and retention of skilled construction workers from both domestic and international sources.

Read more: Australia’s housing crisis is deepening. Here are 10 policies to get us out of it

The biggest landlord subsidy isn’t helping

More than 1 million Australians claim a net rent loss (negative gearing) each year. Even though negative gearing is focused on rental investment losses, it is not strictly a housing policy as it applies to many types of investment.

The impact of negative gearing on the housing system is untargeted and largely uncontrolled. As a result, it’s driving outcomes that are sometimes at odds with the need to supply well-located affordable housing.

The most impactful action the Australian government could take to deliver more affordable rental housing nationwide would involve refining negative-gearing arrangements to boost the supply of low-income rentals. These measures may involve

- limiting negative gearing to dwellings less than ten years old

- introducing a low-income tax credit scheme similar to the one in the United States.

We can learn much from the US, where the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) scheme subsidises the acquisition, construction and renovation of affordable rental housing for tenants on low to moderate incomes. Since the mid-1990s, the program has supported the construction or renovation of about 110,000 affordable rental units each year. That adds up to over 2 million units at an estimated annual cost of US$9billion (A$13.8billion).

This scheme is much less expensive per unit of affordable housing delivered than Australia’s system of negative gearing.

Read more: 4 ways to bring down rent and build homes faster than Labor's $10 billion housing fund

Closer to home, the previous National Rental Affordability Scheme showed the value of targeted financial incentives in encouraging affordable housing. This scheme, available to private and disproved investors, generated positive outcomes for tenants. The benefits included better health for low-income tenants who were able to moved into quality new housing.

A raft of evaluations have demonstrated the achievements of this scheme.

Crisis calls for lasting solutions

Short-term measures such as rent caps or eviction bans will not provide a solution in the near future or even the medium or long term. Instead, these are likely to worsen both the housing costs and health of low-income tenants.

Reform focused on ongoing needs is called for. Solutions that can be implemented quickly include the tighter targeting of negative gearing and the introduction of a low-income housing tax credit.

Talking about change, as the national cabinet is doing, will begin that process of transformation, but it must be backed up by a range of measures to boost the supply of affordable housing. This, in turn, will improve the housing market overall as affordable options become more widely available.

Andrew Beer receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council, the OECD, and the Australian Housing and Research Institute. He is a member of the Board of the South Australian Housing Trust and is the Executive Dean of UniSA Business.

Emma Baker receives funding from the Australian Research Council, the National Health and Medical Research Council and The Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. She is affiliated with the University of Adelaide.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.