There’s a key ingredient missing from the list of your favorite cookie, cake, and bread recipes.

Don’t panic! Even though the recipe might not call for it outright, you’ve been adding it all along.

It’s air. Despite the fact that it isn’t explicitly mentioned, each step in the baking process is designed to trap, introduce, or eliminate air — depending on the desired result. The amount of air and the subsequent size of the air bubbles play a huge role in determining the texture of your finished dish. Air pockets create the recognizable mouthfeel of everything from a chewy, bubbly pizza crust to a fluffy cake. Your favorite bread and desserts start with similar ingredients, but the way the preparation method creates and traps air yields dramatically different results.

A good rise

Trapping air is accomplished through a process known as leavening. The term leaven comes from an old French word — levare — meaning to lift. At its most basic, leavening is the process of lightening a dough. This is what happens when bread dough rises or when cookies puff up in the oven.

Dikla Levy Frances, the author of Baking Science, explains to Inverse that leavening can be achieved in three primary ways:

- With the physical incorporation of air — in other words, whisking a lot

- With the addition of chemical leavening agents like baking soda or baking powder

- With a biological leavener, like yeast.

Frances says air is one of the most important ingredients in baking. You might not think of it as an ingredient at all, but it’s an essential element in the structure of your favorite bread and desserts. As Frances explains, “when we take a bite out of a cake or a cookie, and we have that easy-to-bite pleasant soft feeling, it’s the air.”

How to introduce air

The amount of air included in a baked good, and the manner in which you trap it, really determines what you’re making. Dense, fudgy brownies and light, fluffy chocolate chiffon cake start with very similar ingredients — the differences emerge when you combine them.

In baking, the texture is known as ‘the crumb.’ Cakes usually have a soft crumb. They’re filled with small, evenly distributed air pockets, and they’re tender enough to be broken apart by hand. Rustic sourdough bread has a large open crumb — each slice has big pockets of air surrounded by chewy, stretchy bread. These drastically different textures are created by different ingredient ratios, preparation methods, and, crucially, different leavening techniques.

As an ingredient, air is readily available — it’s all around us. Air from the environment can be physically harnessed during the baking process.

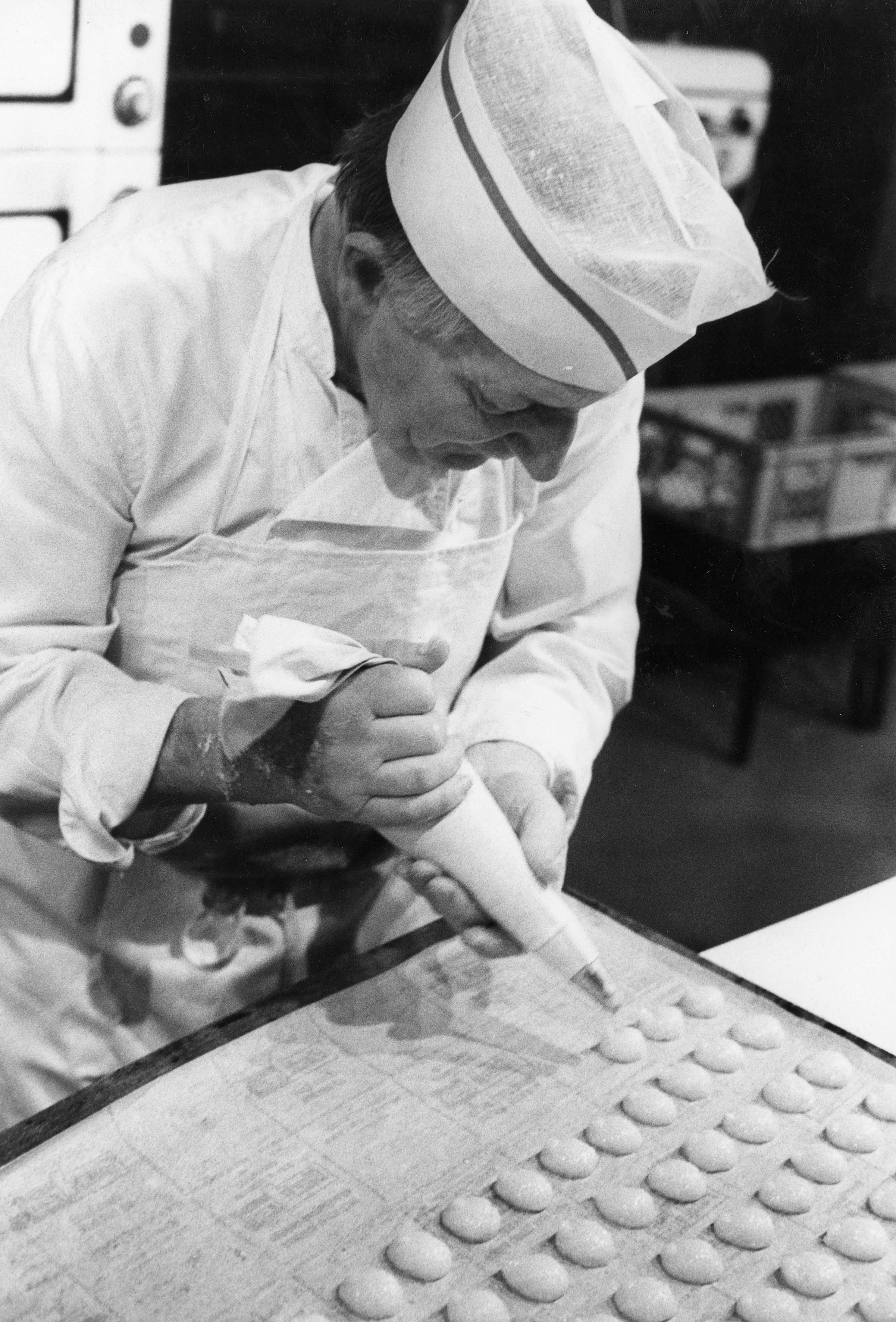

Recipe steps like whipping butter, beating eggs, and sifting flour are all ways to incorporate air during baking. Vigorous stirring traps air inside of the recipe components. If you look closely, you can see the transformation that occurs when aeration takes place. After whipping with an electric beater, butter will transform from a waxy soft yellow to a sunny light shade. Whole eggs will lighten from a deep orange-yellow to a creamy pale hue.

When it comes to trapping air, egg whites are hard to top. The pure protein in egg whites is strong and flexible. When whipped, the proteins unfold and trap air like balloons. This is the method used to give angel food cake its famously light and marshmallowy texture. These physical aeration methods can be used alongside or in place of chemical leaveners. Frances explains how the two techniques can work together, saying, “if you whip the eggs, you won’t need as many chemical leaveners. You can rely on the air.”

Keeping the air

Once the air has been physically incorporated into a dough or a batter, you have to be careful not to lose it. All of the bubbles that were created during the mixing process can be popped if they aren’t handled carefully. This is why recipes call for gently folding in egg whites rather than stirring with a wooden spoon. In order to create lightness, the bubbles need to remain intact long enough for the flour and other ingredients to solidify around them.

During baking, the air becomes locked in. As moisture escapes and proteins denature, the structure of the baked good firms up. By the time the whipped butter melts away, the shape of the cookie has already formed around it, preserving the volume of the cookie. This can be jeopardized if cookie dough isn’t at the correct temperature when it enters the oven. If the butter is too warm, it will melt away quickly. All of the air that was trapped will run out before the protein hardens, and the cookies will lose volume.

Trapping ambient air isn’t the only way to create a fluffy baked good. Chemical leaveners add lightness through a reaction that forms carbon dioxide bubbles. When it comes to chemical leavening, baking powder and baking soda are the primary options for home bakers. Both of these staples rely on the same active ingredient — sodium bicarbonate.

On its own, sodium bicarbonate is a dry white powder. Once it’s combined with a drop of acid, its leavening powers are unleashed. If you think back to back to elementary school, you probably know what this looks like already.

Baking soda + vinegar = one very foamy volcano.

Recipes that rely on baking soda or baking powder harness this reaction. When the gaseous bubbles are released inside a cookie dough or cake batter, the bubbles become trapped. Once the carbon dioxide is incorporated into a dough, Frances explains that “these gas bubbles are light and will find their way up, rising out of their dense surroundings.”

This is what causes the lift. While the cookies are in the oven, the gas bubbles fight to rise to the surface, raising the structure of the cookie along with them.

Baking soda is pure sodium bicarbonate, so, like the volcano, it requires an acidic element to create lift. Its chemical reaction is kicked off by the other ingredients in the batter or dough, often the lactic acid found in butter or milk.

Baking powder, on the other hand, is a mixture of sodium bicarbonate, cornstarch, and powdered tartaric acid. The acidic element required to activate the sodium bicarbonate is already built into this mixture, and the chemical reaction will start as soon as it’s introduced to moisture. Because baking powder already has everything it needs to leaven, it can be used in recipes that are either low acid or ones that will benefit from its tangy alkaline flavor.

Reaction times

In general, the speed of the leavening reaction correlates with the overall cooking time of the recipe.

Baking powder begins reacting instantly upon contact with moisture, making it the fastest leavening agent. This makes it a good choice for quick-cooking recipes like pancakes that will finish cooking and solidify in time to trap the bubbles.

Baking soda needs to find the acidic elements nearby before its reaction starts, which leads to a slightly longer rising time. This makes baking soda a good choice for medium-length recipes like cakes and cookies. Once again, proper cooking is essential to harness the gas once it has been created. If a cake batter is left on the countertop too long before baking, the chemical reaction will occur prematurely, and the bubbles will escape from the batter. The cake will leave the oven feeling heavy and dense.

The bubbles created during the chemical leavening process are small and quick-moving. They’re strong enough to lift a light batter, but they wouldn’t be able to force their way through a dense loaf of bread. When it’s time to add big air bubbles to chewy bread, yeast is the most popular leavener.

Yeast is a living, single-cell organism that Frances refers to as a “biological leavener.” Baking at home usually starts with active dry or instant yeast, but there are thousands of strains of wild yeast, like the kind used to create sourdough, in the environment around us.

To begin the leavening process with commercial yeast, you need to activate it. Yeast becomes active at the correct temperature — between 90º Fahrenheit and 110º Fahrenheit — in the presence of moisture and food. Under these conditions, yeast will wake up, eat any available sugar, and die, expelling carbon dioxide gas in the process.

Compared to baking soda or baking powder, yeast requires a longer time to start acting. This is why bread doughs take an hour or more to rise. During the rising time, yeast is eating available sugar, multiplying, and dying. All of this activity creates a powerful leavener. As Frances explains, “it takes a stronger environment to trap yeast.”

Large yeast bubbles would escape through a loose cake batter. In a bread dough or a sweetened yeast dough, flour has been hydrated and kneaded to develop the gluten. This is what gives the dough its stretchy, elastic appearance. The strength of this dough holds bubbles in as they form.

In the oven

In cakes, cookies, and bread, there’s an important leaving process that works in conjunction with the other leaveners.

Batters and doughs all have some moisture that evaporates during the cooking process, turning to steam. Steam can also act as a tool for leaving. Classic popovers are an excellent example of leavening with steam. Popovers start out as a batter with a very high liquid content and no additional leavening agents. Once they’re in the oven, the liquid evaporates. As the steam rises from the batter, it’s trapped by a web of eggs, milk, and flour. The steam lifts this batter up, creating a large air bubble in the center.

In most cases, the type of leavener plays such a large role in the dish’s character that it can’t be substituted. Swapping whipped egg whites in place of baking soda would result in an entirely new recipe. Using whipped butter instead of melted butter in a brownie recipe might sound like a small modification, but the resulting change would be so drastic that you would basically have made a cake instead.

Of course, there’s always room for harmless experimentation in the kitchen. If you want to observe the power of air, try changing the speed and amount of time that you mix together ingredients next time you make a beloved recipe. Frances doesn’t guarantee this will yield an improvement, just an alteration. And that, in itself, is just fine.

TASTE OF THE HOLIDAYS is an INVERSE series about the science of food supported by Target. Get the inside scoop on your favorite (or hated) nostalgic holiday dishes via our hub, which will update with new stories through December 2022.