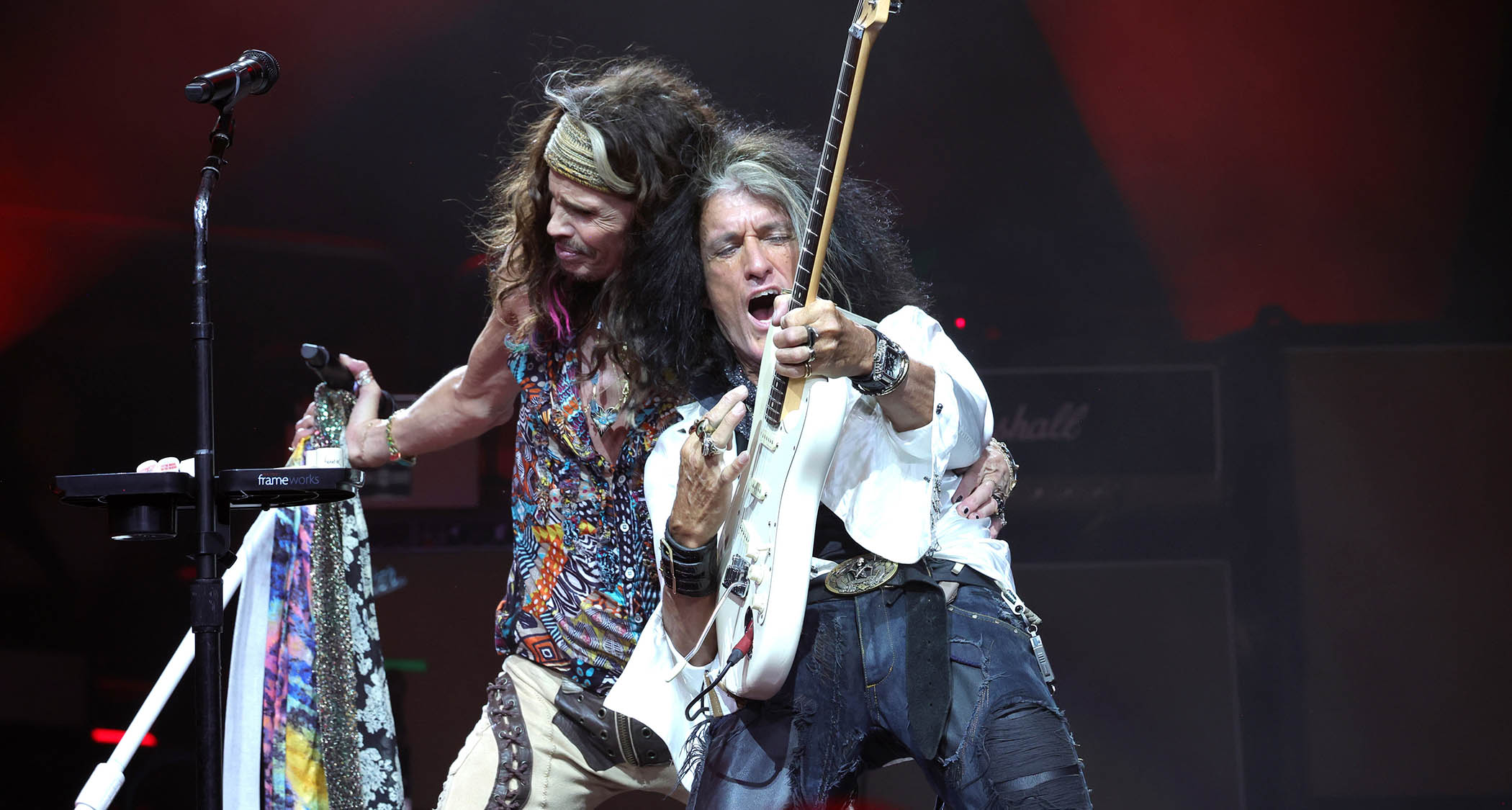

Leading up to August of this year, Joe Perry was busy preparing for a tour. Not just any tour – he was saddling up for what was to be Aerosmith’s rebooted Peace Out tour, the same one that came to a screeching halt after a performance at the UBS Arena in Elmont, Long Island, on September 9, 2023, when normally evergreen vocalist Steven Tyler suffered an injury during the show and fractured his larynx.

But all that changed on August 2, when Aerosmith issued a joint statement informing the world that there would be no second chance at ‘Peacing Out.’

“It has been the honor of our lives to have our music become part of yours…” said the statement that ran across all Aero‑related social media. “Steven’s voice is an instrument like no other. He has spent months tirelessly working on getting his voice to where it was before his injury.

“We’ve seen him struggling despite having the best medical team by his side. Sadly, it is clear that a full recovery from his vocal injury is not possible. We have made a heartbreaking and difficult, but necessary, decision – as a band of brothers – to retire from the touring stage.”

Just like that, Aerosmith, as a touring entity, was gone. Joe Perry, of course, was left reeling to think about what might have been. It’s understandable, as he had spent over 50 years, save for a few lost years between 1979 and 1984, devoted to the Aerosmith machine. The idea that he and his bandmates couldn’t say goodbye on their terms is heartbreaking.

For these reasons and about a million others, when Perry dialled in with Guitarist in mid-August of 2024, he politely informed us that he wasn’t ready to talk about Aerosmith’s end. And who could blame him? Facing one’s musical mortality unexpectedly is one thing, but there’s also the matter of family – which his bandmates in Aerosmith, and the band itself, should be likened to.

In short, Aerosmith’s being forced off the road in such fashion leaves the band with a heavy grief. As such, Perry needs time to mourn. But, thankfully, he was still up for talking guitars, gear, and how today’s landscape is being shaped by all of it.

This brings us to an important question: why is Joe Perry important in 2024?

To start, it’s not about farewell tours or classic albums, nor is it strictly about Aerosmith. The answer is far more multi-layered than you can imagine. But for starters, few so-called ‘classic rock guitar players’ boast Perry’s idiosyncratic legacy.

You can rattle off names like Jimmy Page, David Gilmour, and Brian May. And, of course, all of them are truly genius-level when it comes to their greatness. Page was a studio savant, and Gilmour a master of time and space. And then there’s May, a titan of melodicism and Vox-laden tone. All essential, all quintessential. All decidedly ‘classic rock.’

So what makes Joe Perry – a self-taught rocker out of New England who once wanted to be a marine biologist, who grew up with undiagnosed ADHD, and who powered through break-ups, make-ups, and shake-ups to strut his stuff – akin to a giant striding across the Earth? Well, everything, really.

With Perry, it’s about feel, vibe, and a certain je ne sais quoi. And you better believe it’s swirling all around the man’s orbit every time he takes the stage. That is to say – it’s real. “If you spend all your time learning technique, scales, and all that,” he says, “you’re not really going to write something new and interesting.”

‘Interesting’ is the magic word when it comes to Perry. He refuses to stagnate or be boiled down in an age of clickbait, oversaturation, social media wars, and a landscape often featuring rehashes of things too often seen but featuring little substance.

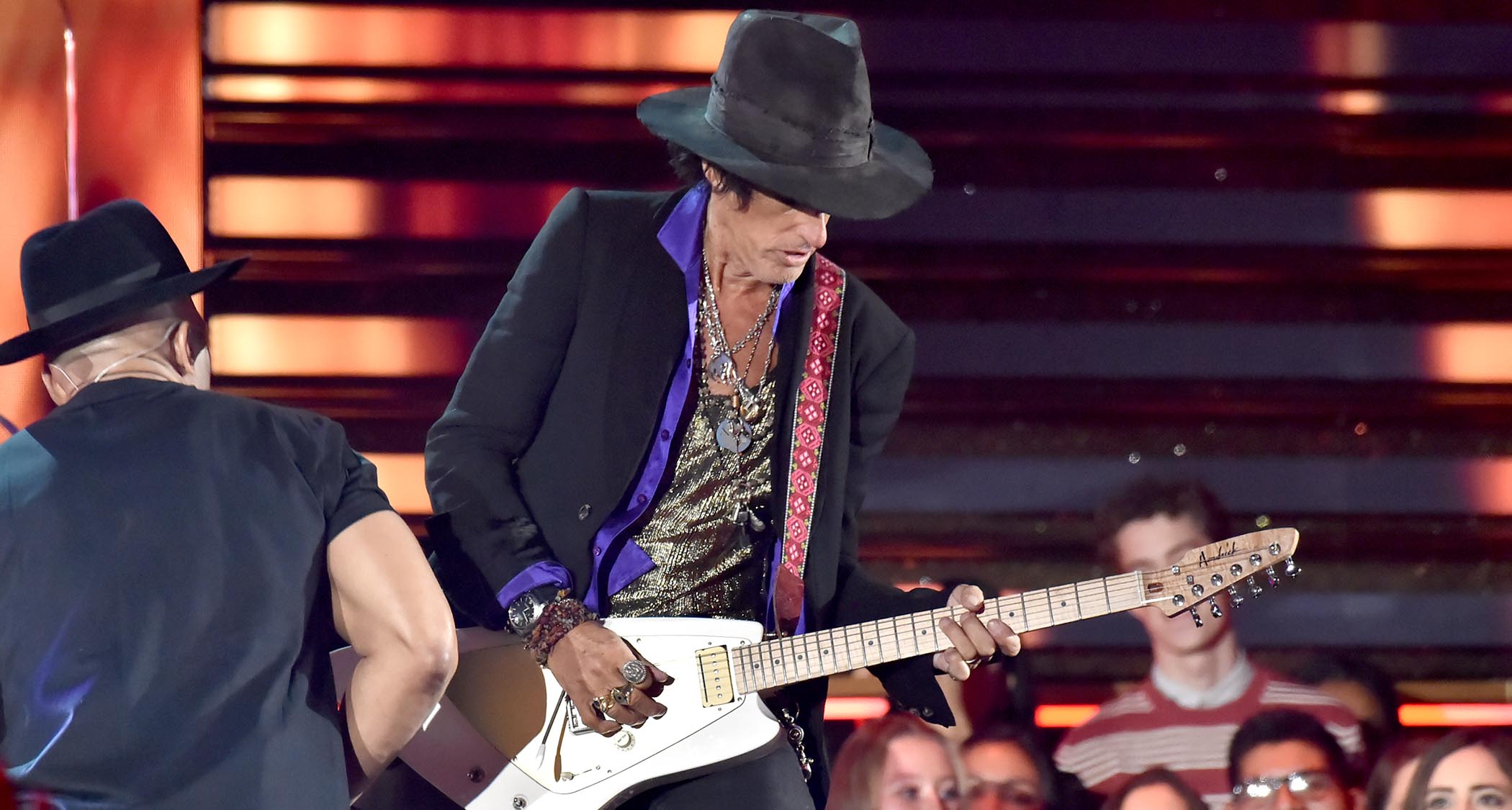

Not many know it, but he’s not a simple Les Paul-slinger or run-of-the-mill Strat devotee. Two minutes spent with him chopping it up about valve amps, speaker changes, weirdo guitars, and pedal accumulation will tell you that.

To that end, Perry is a mad scientist with an array – and ever-changing – pile of stompboxes at his feet, who will remind you as often as you’ll listen that “there are no bad tones.” And looking back on his career, he’s always been that way. It’s a way of thinking about life, and playing guitar, that can’t be taught. You’ve either got it or you don’t. And Joe Perry’s got it in spades.

“You have to teach yourself to break away,” he says. “Technique is a way to get somewhere, and in and of itself, it’s fine. Fucking go for it if you want, but if you want to play the kind of rock ’n’ roll that I like, there’s more to it. There’s infinite numbers of chords that can help you, but it’s really what you want to do with the guitar.”

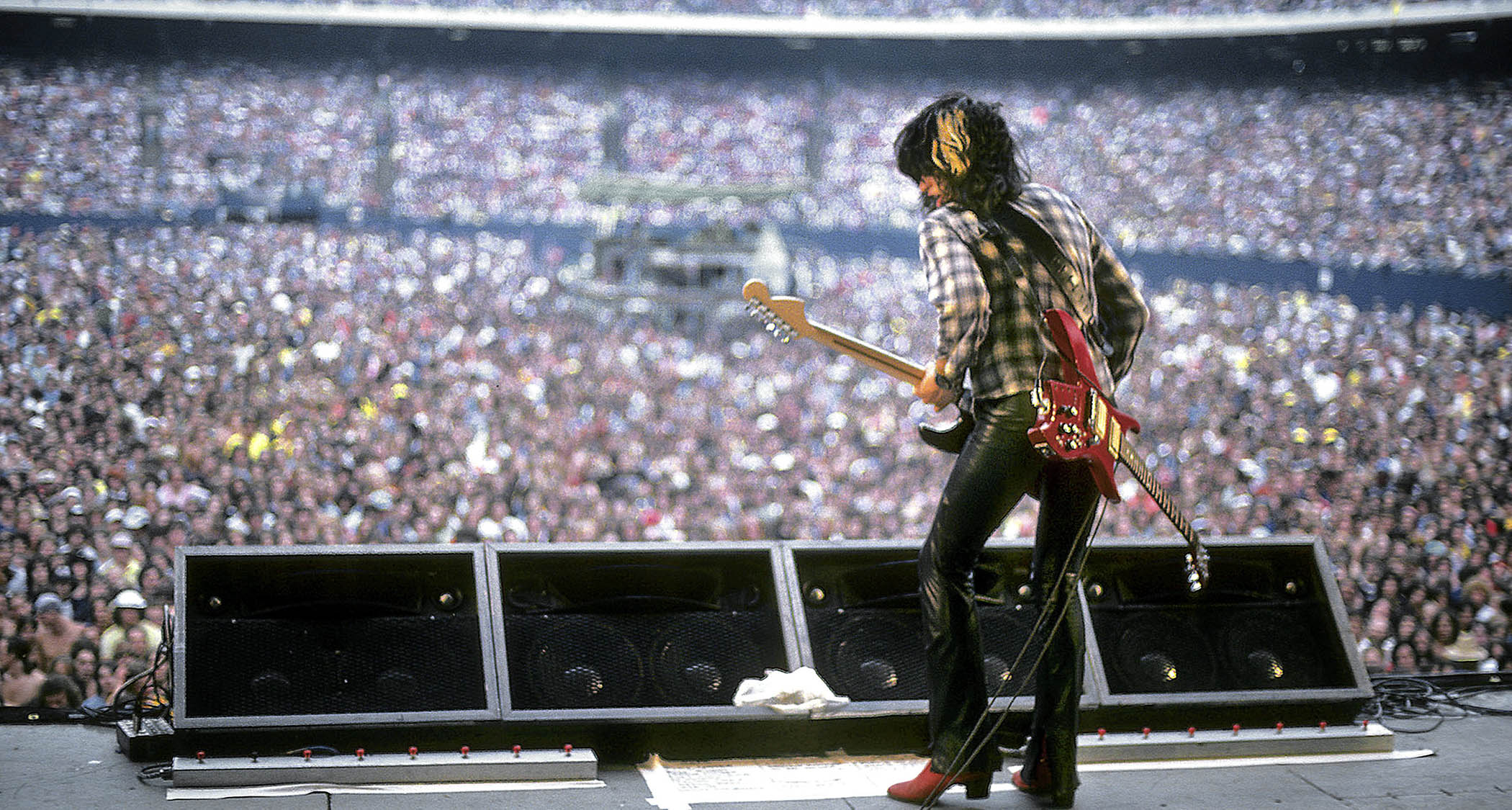

Perry knew that from the jump, feeling his way through the world as a New England kid with a guitar in hand, and a dream he was instinctively prepared to lay it all on the line for. There have been a lot of kids who were like that, but Perry was different. He felt a kinship with his instrument and understood its place.

“The guitar was a weapon of rebellion,” he explains. “People were afraid of that music. They called it ‘the Devil’s music.’ They called it all kinds of things. It was too sexy, but it was just three chords and a nasty feel. If you walked down the street with a guitar case, it was a guarantee that somebody would go, ‘Wow, you play guitar?’ It was a chick magnet [laughs].”

But it’s not like that any more, not for Perry or anyone else. “It’s just so mainstream now,” Perry says. “And it’s great – it’s such a great instrument. It’s adaptable to many things, but I think the era of the guitar hero is kind of… There will still be guitar heroes, and there will still be people on the cover of Guitar World, but it certainly isn’t going to be… I’m hearing a lot of great rock ’n’ roll, but it’s not guitar-centric.”

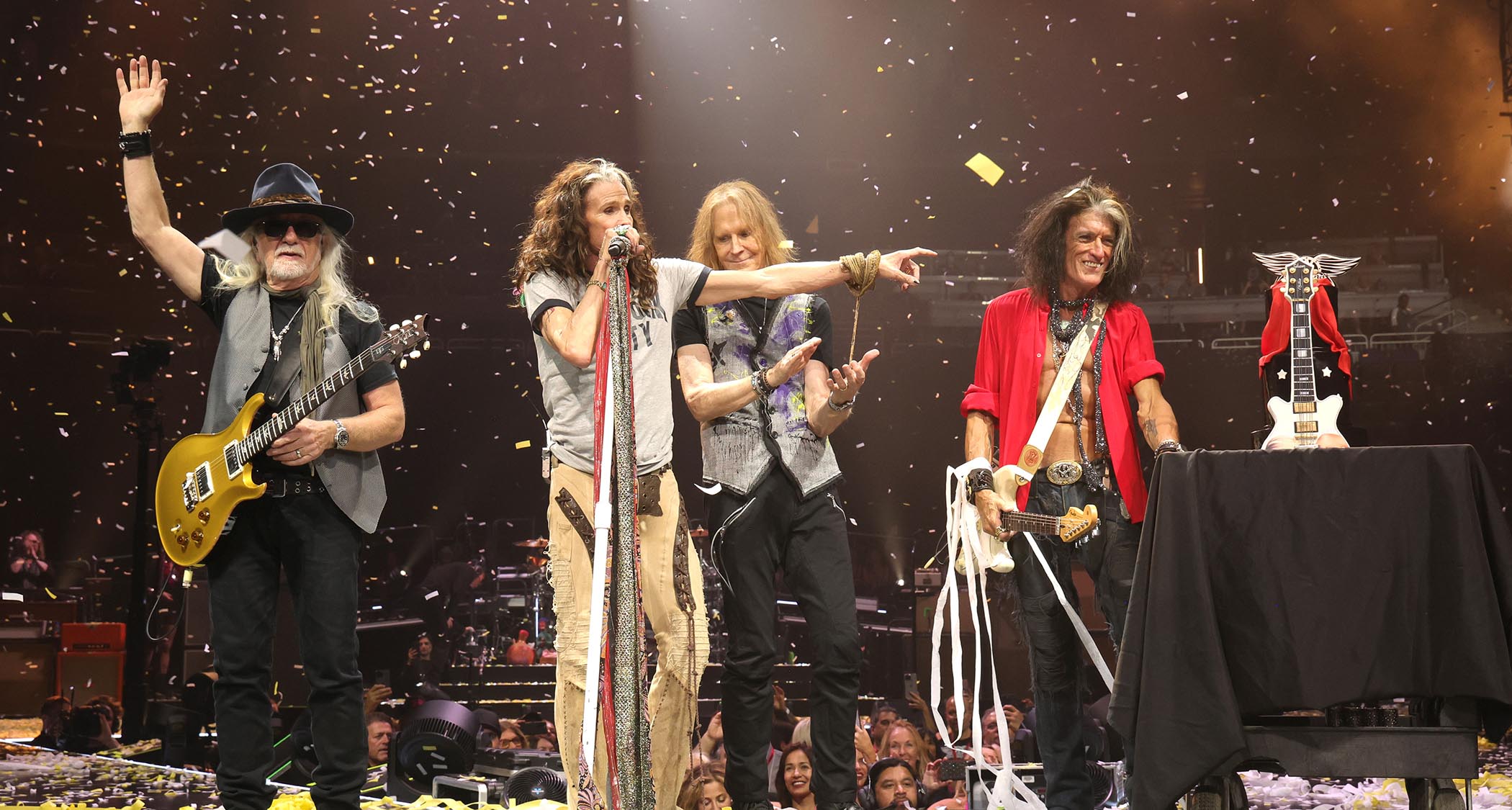

Losing Aerosmith doesn’t help that. The final words of the band’s internet-breaking statement are still ringing in our ears in place of Perry’s sleazy riffs and blues-blistering solos: “We are grateful beyond words for everyone who was pumped to get on the road with us one last time,” the band’s statement said in closing. “A final thank you to you – the best fans on planet Earth. Play our music loud, now and always. Dream On. You’ve made our dreams come true.”

With more rock giants falling off each year, the scene is changing. KISS hung it up in December of 2023, REO Speedwagon announced their end in September 2024, dozens of farewell tours are afoot, and Aerosmith are gone now, too. But Joe Perry isn’t. He’s got more to do – and he damn well plans to do it.

In fact, he’s got plenty to say about the current trends in guitar. “You might have a guitar solo in there,” he says, “but it’s not the basis of the song. Guitar has just become so accepted; it isn’t a symbol of rebellion any more. For better or worse, it’s just another instrument.”

But don’t get it twisted; Perry doesn’t feel the guitar has been relegated. If anything, its appeal is broader than ever. “It’s an amazing thing that’s happened over the last 70 years,” he smiles. “Guitar is global. It’s a global market. I keep my eye on it, but I certainly don’t sweat it or worry about staying relevant.”

With Aerosmith in his rearview mirror and more than seven decades under his studded leather belt, Perry has learned a lot. He’s lived dozens of lives, and even though his contemporaries are dropping like flies, Joe Perry forges ahead. Aerosmith might be over, but Perry is just getting started. And as always, he’ll do it as classic rock’s ultimate chameleon.

“I stick to what I do best, you know? I’m sure I’ll be doing something, whatever, down the road. But who knows, really? One thing I know for sure that will stay the same is that everything is going to change.

“Anybody that goes to Berklee and learned all the techniques and all that stuff, that’s great,” he says. “But what are you going to do with it? That’s what it’s all about – what you do with it. Do you want to write songs, or do you want to impress people with how skilled you are? There’s a market for both, you know, if you want to try to make a living playing guitar.”

Was there a lightning bolt moment as you were coming up that led to your growth as a guitarist?

“That’s a big question. I guess realizing at the very start that it was pretty much about getting a guitar that felt right in your hands. It’s a weird thing because, like any guitar player, I can plug into another player’s rig, fiddle with the knobs, and end up sounding like that person.”

If you’re striving for really distorted sounds, you’re gonna lose the tone of the guitar. If you pile overdrive on, it’s all gonna sound the same no matter what guitar you use

So, it’s not so much about the rig but how you use it?

“Not so much the rig, it’s how you hear the sound – and adjust to it. If it’s louder, softer, and where your picking hand is, like if it’s close to the bridge or closer to the neck, so much is dependent on getting to know the sound you want. And over the years, the equipment choices just exploded.”

You’re something of a mad scientist when it comes to guitar pedals and gear. Was that always the case for you?

“When I started, I think you had to search around for a fuzz pedal, you know? I mean, I look in the guitar magazines and there’s probably a dozen new fuzz pedals every month now, so it all comes down to really dialing it in. You can be stuck someplace, but you can still get a sound that’s usable. It’s up to what it sounds like to your ear. There’s no other magic to it than that.”

As a self-taught player with a deeply distinctive and successful style, do theory and theatrics mean much in the grand scheme?

“Well, I have a learning disability [ADHD]; it’s tough for me to focus. But if you can get some of that stuff, along with whatever you’re learning by listening to other players, that’s great. If you can get some theory and technical knowledge, it can only help. The problem is not getting too hung up on it.”

I learned that some of the best riffs are the simplest. The ones that people can sing to are the ones

Do you think there’s a lot of that happening in recent years?

“There was a video going around, and maybe you’ve seen it, but there’s this player [Phil Taylor], who was the fastest on the planet and playing Flight Of The Bumblebee. He starts as fast as you think a human can do it, and then he bumps it up and up. It’s blinding, and you can’t even see his hands.

“It’s incredible technically, but it’s a mechanical thing, though there’s skill there and he put in the time. But if you can write a song that’s as catchy as Flight Of The Bumblebee, that would be something. Learning theory can be a huge help, and if you want to do it, more power to you. But I wanted to play the music people wanted to hear and be in a band that entertains people.

“I learned that some of the best riffs are the simplest. The ones that people can sing to are the ones. I’m a fan first. I went on the road with John McLaughlin with Aerosmith in the early '70s and – holy shit, man – those guys could play. But you couldn’t dance to it. I have total respect for that kind of talent, but it kind of left me cold.”

Since you’ve never leaned on theory, did unlocking the fretboard come easy for you?

“I was just listening to what other people were playing and trying to copy that. I was never very good at it, but figuring out where they were putting their hands and trying not to sound like anybody else was important. And I wasn’t skilled enough to have something to replace it with; it took me a while to get my own voice. But I think anybody that’s self-taught breaks the mold.

“You know, sometimes I’ll try to learn a riff just to see if I can do it. I don’t know if it’s going to help me, but sometimes it will. So many times, the best riffs have come when I pick up a guitar that I’ve never played before because it sounds a little different. I’ll play some riff that’s just out of hand, and all of a sudden it sounds different and I’ve got the basis of a song. You’ve got to keep your ears open.”

Your open-mindedness regarding gear is something that’s not championed enough. People often assume it’s all Les Pauls and Strats, but you have a 600-guitar collection of oddballs.

“I was never hung up on getting one sound and going, ‘That’s it,’ you know? From the very beginning, almost everybody I knew had one guitar, maybe two. If you wanted a different guitar, you traded sideways. I listen to a lot of guitar [being] played and there are so many different sounds; it’s really inspiring.

“Take a song like Back In The Saddle; I wrote that riff on the Fender six-string bass. The only reason I knew about the six-string bass was because I used to see Peter Green with Fleetwood Mac, and during one of their jams, he would pick one up. I thought, ‘When I get a little money, I’m gonna get one.’

“So I got one, started messing around with it, and suddenly this riff came out. The whole introduction to Back In The Saddle and all those riffs just fell into place. It wasn’t like I said, ‘I’m gonna write a song with this’ – it was just this riff that was suddenly there. I grabbed it, recorded it, showed it to the band, and there it was.”

And events like that only ended up fuelling your guitar-collecting habits, right?

“Yeah, that’s why half of the guitars in my collection are funky, weird guitars. When I started collecting guitars, it was this Les Paul or that Strat, but I was looking under the dust and finding these $100 or $200 guitars with no names on them that I’d never heard of, but they had a funky sound. I ended up with a collection of those kinds of guitars. I still go back and pick them up. And when I do, I make sure I have a tape recorder nearby.”

Were you ever hung up on new gear versus vintage gear?

“No, but I might have bought something new once I got a little money. I remember being in the Record Plant when Aerosmith was recording the second record [Get Your Wings, released in 1974] and I needed a Strat.

“My one was probably from ’68 or ’69 and it was stolen. I sent my tech down to Manny's Music and said, ‘I need a Strat – just make sure it’s black’ [laughs]. It was probably a 1973 Strat, but it worked and was fine. That’s probably the same Strat I played the solos from Sweet Emotion and all those songs on.”

You’ve often said, “There are no bad tones.” That’s important, as it’s easy to get hung up on one tone and reject others as ‘wrong’ or ‘bad.’

“With effects and pedals that create tones, it’s about how you use them. Even something that sounds broken might be just the thing. There’s an old joke, but it’s pretty much true, and it’s that a Marshall sounded best probably when it was 15 minutes away from blowing up [laughs].

“That’s when the tubes were running hot, and maybe the preamp was driving the power amp too much and the transformer was overheating. But you’d get this sweet sound and, sure enough, it would start smoking.

“It’s tough to get an amp to blow up now. They’ve made them so bulletproof. I mean… nobody wants to have their amp fry in the middle of a show, and nobody wants to return their amp after they bought it, but I think everybody’s got a favorite tone or a working tone. I mean, you can use something that’s absolutely ratty.”

“The solo from Janie’s Got a Gun, that was a pretty ‘bad’ ratty sound. I had a Chet Atkins signature guitar, which was meant to be an almost acoustic-sounding guitar with an early piezo pickup. The nature of it was, if you turned it up, it would sound very ‘not acoustic’ [laughs].

“I plugged into a 15-watt Marshall practice amp – a transistor amp with a tube – and when I started cranking it, it sounded pretty nasty. I turned everything all the way up, played it and the producer said, ‘It sounds terrible. That’s never going to work.’ I said, ‘Listen, just run the track, and let me give it a try.’

“And it sounded like what I wanted it to sound like. I wanted it to sound nasty and angry. I wouldn’t use that guitar sound on too many other things, but it’s an example of taking a sound that most people would turn their nose up at, but it worked for that track.”

You mentioned ‘working tones’ before. What’s the secret to the quintessential Joe Perry working tone?

“Not too much distortion: I don’t like too much distortion because it takes away from the actual tone of the guitar. I don’t want to squash the sound. I’m really conscious of really getting clean tones. But if you’re striving for really distorted sounds, you’re gonna lose the tone of the guitar.

“If you pile overdrive on, it’s all gonna sound the same no matter what guitar you use. But if that’s what you want for your style and what works, go for it. I like a sound with some definition and some of the guitar’s tone. I lean toward a cleaner sound.”

Many people don’t realise you’re a big pedal guy. Do you have any always-on pedals, with the knowledge that you’re very into clean tones?

“I like a little bit more compression – not so much added distortion but getting that grind from the actual preamp pushing a bit. So maybe I’ll have a boost pedal, but lately, over the last 10 years, I’ve been using a compressor. It’s like an always-on thing. I can get more sustain [that way] without having to get as much distortion.”

Through all that exploration, have you ever found yourself at a point where there were too many guitars, too many amps, and too many pedals to where you felt lost?

When I’m not feeling it, my wife always goes, ‘Just go down and play some blues.’ I’ll go and put an old John Lee Hooker or Muddy Waters record on... some of the early stuff just brings me back to the basics

“My objective is to play songs in a band, you know? If I start feeling like the guitar isn’t doing it, I go back and listen to the shit that got me to like guitar in the beginning.

“When I’m not feeling it, my wife always goes, ‘Just go down and play some blues.’ I’ll go and put an old John Lee Hooker or Muddy Waters record on, and I don’t know… some of the early stuff just brings me back to the basics. But it’s not so much the guitar that I hit walls with; it’s coming up with the inspiration to write songs.”

Is there anything on guitar you can’t do but wish you could – and have you found a workaround for that?

“I found that when I get on stage, I tend to want to squeeze the neck and tighten up. I didn’t realize that, but I found myself really getting excited and I’d stiffen up and make it so I couldn’t play as fluid as I was, say, 15 minutes before in the dressing room.

“I’m not sure what it was… but I read an interview with Keith [Richards] in 1980 or something, and he said, ‘Play with a light touch.’ That’s when I realized I was holding on too tight. You never know… sometimes it takes a word or a lick, and a lightbulb will come on.”

When you look at the modern guitar scene, what are your thoughts on what you see?

“I think there’s a lot that’s still going to happen. I kind of doubt that there’s going to be another Jimi Hendrix, Jimmy Page, or Eddie Van Halen; that was a time and an era. Those were standout guys who turned the world upside down and changed the way people heard guitar in our little world. But it’s not going to be like that any more.

“They used to call Alvin Lee ‘the fastest guitar player in the world.’ He was ripping it up, but he played the pentatonic blues scale faster than anybody else for those five minutes. But it was a one-trick pony and, really, it doesn’t matter who is the fastest. Like that Flight Of The Bumblebee guy, you go, ‘Wow, that’s pretty cool,’ but he’s not gonna draw crowds like Taylor Swift.”

So, what’s the guitar’s place in modern popular music?

“The thing is there’s so many people out there now. The population has increased from, what – five billion [in 1987] to eight billion? There’s room for more kinds of music to be successful, which is really good for people who want to make a living. As far as guitar, there’s always going to be advances in new things, and there’s always going to be those who carry on the tradition. It’s just a different thing.”

Disco slammed into us. Frankly, I liked a lot of it. There was some pretty funky stuff and great songs, but the press was like, ‘Rock ’n’ roll is dead. Disco is king’

As an older artist, do you find it difficult to stay relevant?

“It’s been a long time since I worried about that. I still listen to music, I still like music, and I still listen to all the same stuff. It’s funny, the first taste of what you’re talking about was in the '70s when disco slammed into us. Frankly, I liked a lot of it. There was some pretty funky stuff and great songs, but the press was like, ‘Rock ’n’ roll is dead. Disco is king.’

“And then there was punk. All the punk guys were saying, ‘Oh, fuck The Rolling Stones. They suck.’ They had to throw out the old to have something new. You start seeing a lot of stuff that was pushed by record companies because they want the newest, latest thing. And then there was the MTV thing, which fucking blew the roof off the business.”

It sounds like you’ve always been fearless in the face of genre change or just okay with riding it out…

“That’s really it. When Nirvana and Pearl Jam came out, suddenly that was the ‘new’ rock ’n’ roll to me. I just put it next to AC/DC or the next Aerosmith record. It all sounded like rock ’n’ roll to me. But the record companies made a big deal out of it and singled out every band from Seattle, which was nothing new, either.

“The record companies try to make you think it’s something new, but if you listen to all the alternative guys, the only thing different is they weren’t wearing Spandex [laughs].”

As you said, there probably won’t be another Hendrix, Page, or Van Halen. But the fact is that there probably won’t be another Joe Perry, either. You’ve influenced and innovated sounds, gear, and people. Have you reached a point where you can reflect on your journey and impact as a guitarist over the past 50 years?

“Oh, I don’t know. I don’t really spend much time thinking about that. Obviously, when somebody comes up and says, ‘When I first heard Rocks, or Walk This Way with Run-DMC, I discovered Aerosmith,’ I say, ‘Well, thank you very much.’ I mean… that’s what we set out to do. But other than that, I’m still puzzled.

“I remember this poll that came out on Billboard, where they wanted to ask a bunch of other guitar players about the most iconic guitars of the last however-many years. Everybody, I guess, voted and my name made the list, which was kind of nice. They listed three of my guitars, and one of them was the 10-string [BC] Rich Bich. And for all the notoriety, it’s probably the least-played guitar of the ones people know.”

So why do you think it’s so often singled out?

“I mean… there was a picture of me holding it up on the Live! Bootleg record, but it’s funny when I run into guitar players now and they always ask me about that guitar. It’s like, ‘I probably used it on a bunch of songs on my first solo album [Let The Music Do The Talking, 1980]’. It’s one of those guitars that works really good for certain things, but it’s funny they didn’t mention any of my Strats or whatever.”

Is there anything you’re experimenting with at this stage that might significantly impact you going forward?

“I have a 12-watt Silktone amp, and I’ve been messing with speakers a lot. I think speakers have become a bit too ironclad. One of the things about those early amps is that when you push them to the edge, they have a sound that isn’t distorted but just a certain sound.”

“I have a friend named Jack Donahue [veteran audio engineer], who sent me some eight-inch Bogen speakers that he re-coned with really thin paper to make them more like the old ones.

“Jack is in Boston, and the re-cone made that Silktone sound great. So I’ve been experimenting a lot with speakers. I had some speaker cabs made by Marco Moir, my old guitar tech, with a variety of size baffles, watt-ratings, et cetera. It’s amazing how different speakers can be made with the same amp.”

Do you have a favorite or go-to speaker at the moment?

“My favorite right now… There’s a lot out there, it’s a matter of taste. The 10-inch Alessandro Custom 1959, 20-watt rated and made by Eminence, is probably my favorite. They do a 12-inch that’s got a little higher rating. If you’re gonna use one, just be careful of how much power you pump into it! But Weber makes great ones, and Vox ‘blue stacks’ are great. I like vintage Jensens because I like lower-watt-rated speakers. It’s a tone, not a volume, thing.”

Would you single out any one guitar as most associated with your legacy?

“Well, my favorite guitar is the one I call the ‘Burned Strat.’ It looks all burned up and has Seymour Duncan [P-Rails] pickups that combine a Strat pickup and a P-90 in a humbucker slot.

“That’s my favorite guitar. But it’s kind of hard because I’ve played a bunch of different guitars over the years, so it’s funny that the Rich Bich is the one that’s been chosen to attach to my legacy [laughs].

“You just have to chuckle. That’s all, you know? I mean, all that stuff is out of my hands. And that’s the other thing that you learn pretty early on: if you can deal with all that stuff, you can deal with the rest of it. You can just let it go. Otherwise, you’ll spend all your time freaking out.”