What are the limits of the human body? How much pain and suffering can our bodies withstand? What would we be willing to endure for our loved ones? Is solidarity something natural, or does it come to us only in certain moments of our lives?

These questions do not have one answer. They are the subject of numerous discussions and interpretations, and have been asked in countless groups, societies, cultures and civilisations, becoming the topic of both scholarly and everyday debate. When faced with tragic situations, people have been forced to confront them in some way, though often with varying degrees of success.

Disaster

13 October 2023 marked 51 years since an incident that thrust some of the issues raised above into the limelight.

Uruguayan Air Force flight 571, chartered by a rugby team and their friends and family, was flying to Chile for a friendly fixture. It never reached its destination. After an accident in the Andes Mountains, the remnants of the fuselage were left at an altitude of 4,000 metres, among mountains and towering, mile-high peaks, in the midst of snowfalls not seen for decades and temperatures hovering around minus 40 degrees Celsius.

In the surrounding area there was not even the faintest hint of civilisation, nor any chance of communication (the radio was broken, there was no satellite tracking, GPS or phones), nor anywhere to find even a scrap of food once the scarce provisions (a few chocolates and some wine) were finished. This place –known as the “Valley of Tears”– was extremely hostile to any kind of life.

Of the 45 passengers and crew, only 16 survived. Some died in the accident. Others shortly after from their injuries. More subsequently died in an avalanche that occurred in the days following the plane’s initial impact against the mountains. This event, and what happened in the weeks and months after, came to be known in the Uruguayan and international press as either “The Andes Flight Disaster” or “The Miracle of the Andes”. What we have seen thus far was the disaster. The miracle is what came after.

Miracle

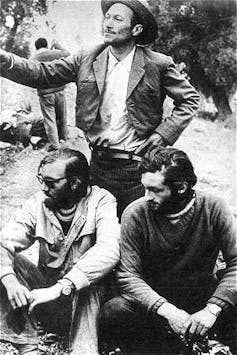

The group who managed to hold out –young men for the most part, in good physical shape, from upper middle class Uruguayan families and members of a religious school– survived in these harsh conditions for 72 days.

After hearing on a transistor radio that the search was over, with both Uruguayan and Chilean authorities presuming them dead, one of the survivors addressed the others and announced that this was good news. To his companions’ confusion, he stated that they were going to get out on their own. And they did.

It is at this point that we can begin talking about aspects such as resistance, creativity, solidarity, fraternity, empathy, resourcefulness and even utopia. These uniquely human ways of surviving are what make us so extraordinary as a species.

Making warm clothing from what was left of the seat covers, sharing what little they had and eliminating any trace of selfishness, conflict, individualism or privacy were necessary to overcome the desperate conditions of cold, hunger, tiredness, weakness, fainting, pain and constant fear.

They even went to such lengths of determination as to eat the flesh of their dead friends in order to survive, to the point of scraping their bones to obtain calcium. This was the subject of much subsequent debate among wider society, some of whom branded them as cannibals.

“The Society of the Snow” was the name given by the survivors themselves to this form of coexistence that was born among them. An entirely new way of imagining society became necessary, as the rules of the previous world had vanished without a trace. At the end of the day, as Spinoza said, “no one knows what a body can do”, and the most fully human thing is to push boundaries.

Two of the survivors walked through the mountains in search of help for 10 days without anything that even resembled climbing equipment. They travelled 60 km to finally reach the valleys of Chile where a mule driver spotted them on the other side of a river and was able to begin the rescue.

In the helicopters that took those two friends to join their companions, the pilots remarked that it was impossible to travel that route on foot, or to survive so many days of snowstorms without food or proper warm clothing.

Physical ability and the spirituality professed by some of the survivors were some of the causes given for their survival. There are many other factors, of course, that have to do with the human ability to press forward. As a species we push limits, we are creatures capable of making and keeping promises and looking to the future. Care –according to Heidegger’s three principles of possibility, the fact of existence and falling– is what makes us fully human by affirming that a group, simply by being a group, has a common goal.

From The Impossible to Society of the Snow

Society of the Snow is also the title of a book which features the survivors’ testimonies and has recently been adapted for the big screen in a film directed by Juan Antonio Bayona (The Orphanage, The Impossible, A Monster Calls)

What took place half a century ago serves as a reminder that “impossible” is nothing more than a word that someone, at some point, will ultimately banish from our vocabulary.

Eleder Piñeiro Aguiar does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.