During a summer jam-packed with delays on the Kennedy Expressway and the L, Gabriela Jirasek says something you don’t hear often these days in Chicago.

Her commute from Morgan Park to downtown on Metra is “wonderfully consistent.”

Jirasek, who works in the city’s Planning Department, is not the only one to praise Metra for offering a safe, comfortable and dependable ride. But even the region’s commuter rail can’t shake a looming fiscal cliff faced by transit agencies everywhere and the reality that work life, and commuting habits, are indelibly altered in COVID-19’s wake.

The 9-to-5, five-days-a-week office commuter is a species on the brink of extinction. And that reality poses an existential crisis for Metra.

Now the agency’s post-pandemic plans are coming into focus, and commuters could soon feel changes from some increased fares to new ridership packages.

But perhaps the most interesting shift is Metra’s attempt to market itself as more than a vehicle to get workers downtown.

“We feel the need to really market ourselves to attract new riders,” said Michael Gillis, Metra’s director of communications. He describes a futuristic vision of people using Metra for non-work trips, such as running errands or visiting destinations like Brookfield Zoo.

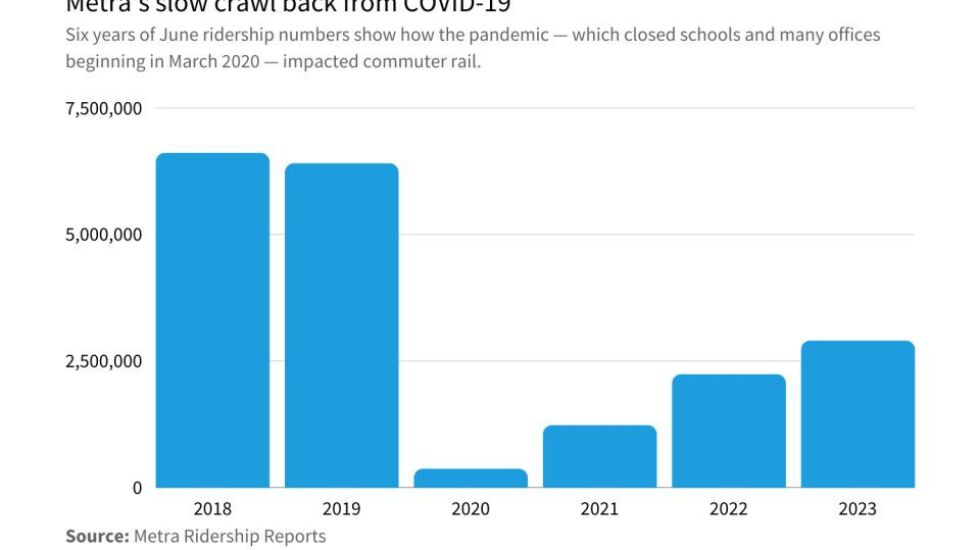

Ridership on Metra trains was up recently. According to agency data, Metra registered 2.9 million passenger trips in June, which was the highest month since the pandemic began. By comparison, the agency counted nearly 6.4 million rides in June 2019.

In recent months, Metra has proposed an extensive fare overhaul and zone restructure, which its board plans to vote on in November. The proposal is meant to address the way commuters’ habits have changed — and is an attempt to draw out the federal relief money the agency received as a buffer when the pandemic clobbered ridership numbers.

By the end of 2025, however, that funding is expected to be depleted, and Metra says the new fare structure will not come close to softening the blow of a predicted fiscal cliff. A state-appointed panel is looking at possible solutions.

In perhaps the most controversial part of its new proposal, Metra wants to nix its 10-ride pass, which is a longtime favorite with passengers. Instead, the agency would replace it with a bundle of five-day passes at the same price.

Gillis said the decision is based on data that shows most people who buy the 10-ride pass typically use it for two trips per day — therefore, he argues, the bundle is an equal alternative.

But it’s not a 1:1 exchange. The new package gives riders less flexibility to share the pass in a group or to spread out the rides over a longer period as someone would if they sometimes use Metra for a one-way ride.

“That’s a way of life for many people … and there’s some risk taking that away,” said Joseph P. Schwieterman, a DePaul University professor who specializes in transit and urban planning.

Metra also seeks to do away with its 10-zone structure and replace it with four zones. Under the proposal, a one-way ticket to downtown would cost $3.75 from zone two, $5.50 from zone three and $6.75 from zone four.

Metra’s current one-way tickets range from $4 to $9.50, depending on distance. While the proposal would increase the cost for some riders year over year, the prices remain below pre-pandemic pricing, according to Metra.

The promotional $100 “super saver” monthly pass rolled out last summer will go away. New monthly passes will range from $75 to $135.

The plan is also focused on promoting non-downtown trips. To encourage a trip to Brookfield Zoo, for example, one-way tickets that don’t include a downtown starting point or destination would cost $3.75 regardless of distance.

What isn’t changing: Metra’s locked-in timetable.

As rider David Klein put it, “You have to live and die by the Metra schedule, which is really frustrating.” Klein, who works at a bank, said if he gets pulled into something at work, it can set him back a whole hour on the train schedule.

Even if Metra wanted to add more frequent trains — which Gillis said it does — that change can’t happen overnight. Mixing up schedules would likely require infrastructure updates and new agreements with the freight railroads that share tracks with Metra. All that would come at a cost.

For now, as Metra tries to adapt, its loyalists continue to express deep appreciation for it.

Aviva Bollinger, who lives in Evanston, started taking Metra right before the pandemic after years of driving to her downtown marketing job.

“If I have to sit in traffic for one more minute,” she said, “I’m probably going to rip all my hair out.”

Metra is collecting feedback on its proposed fare changes at 2024fareplan@metrarr.com.

Courtney Kueppers is a digital producer/reporter at WBEZ.