Local educational leaders decried Thursday’s Supreme Court decision that ended affirmative action in higher education as “an attack on people of color” that stunts racial progress, and administrators vowed to continue helping students of color in Illinois.

The long-anticipated ruling by the conservative majority in the nation’s highest court sends colleges and universities back to the drawing board in their attempts to diversify student populations. Affirmative action had been upheld under Supreme Court decisions since 1978.

University leaders in Illinois said Thursday they are reviewing the ruling to ensure they are complying with state and federal laws but emphasized the role that diversity plays in education.

In a letter addressed to the Northwestern University community Thursday, President Michael Schill said he was “deeply disappointed” in a decision that will make it more difficult to promote diversity and inclusion on its campuses.

“There is much to find problematic in the Court’s decision, but for me, among the most troubling elements is the doubt it casts on the importance of a diverse class in enhancing our educational mission,” Schill wrote. “Bringing together people of different backgrounds, viewpoints and experiences enables us to learn from one another and propels our research, arts and discovery to new levels, allowing us to have an even greater impact on the world.”

Leaders at the University of Illinois system said a diverse student and teaching community “is simply essential to an academically excellent education.”

“The University of Illinois System will continue to open its doors wide to all deserving students — including those for whom opportunities may have been unfairly limited,” wrote system president Tim Kileen and chancellors of the Urbana-Champaign, Chicago and Springfield campuses in a statement.

University of Chicago President Paul Alivisatos and Provost Katherine Baicker said in a letter to students and faculty that diversity has “helped underpin and enable the environment of rigorous research and learning that characterizes” the school.

Northeastern Illinois University President Gloria J. Gibson said in a statement the ruling will “stifle the advancement that education has provided for many from underrepresented and underserved communities.

“As a Hispanic-serving and minority-serving university, we know from firsthand experience the value of multicultural points of view in and outside the classroom. … [We] are committed to continue fighting to close equity gaps for Black, Latino, low-income, working adults, and rural students, and we will continue working to make college more affordable.”

Paul Gowder, a law professor and associate dean of research and intellectual life at Northwestern, said “universities can still produce equity and inclusion even after this decision.”

“This is a narrow ruling,” he said. “The Supreme Court has not said anything about, for example, pipeline programs where universities try to ensure they have a diverse and equitable applicant pool. The Supreme Court has not said anything about universities working to build environments that are hospitable for people of non-majority backgrounds.”

Alvin Tillery, a Northwestern political science professor and director of the Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy, said the ruling largely affects the 100 or so most elite American universities where test score gaps — usually determined by family income and access to test preparation — lead to disparate admissions between racial groups.

While many experts predict universities will face an avalanche of lawsuits around their affirmative action practices, Tillery said he wonders whether the Supreme Court decision might also lead to litigation that targets admissions of alumni family members.

Northwestern prof. Alvin Tillery wonders whether SCOTUS' affirmative action decision might lead to challenges to legacy admissions.

— Nader Issa (@NaderDIssa) June 29, 2023

“Princeton didn’t desegregate until 1977. Having a legacy entitlement at Princeton is essentially a white entitlement. So can schools do that now?” pic.twitter.com/kVSkCbaLD8

“Something like 30% to 40% of the spaces at these elite schools are encumbered before admissions even starts ... because of the use of legacy admissions, athletics,” Tillery said. “Because of the nature of our society ... those two categories are filled with affluent white people. And so what are the knock-on effects of saying you cannot use race at all in admissions?

“Princeton doesn’t desegregate until, I think, 1977 when Justice [Sonia] Sotomayor gets there. So having a legacy entitlement at Princeton is essentially a white entitlement. So can schools do that now?”

The affirmative action cases that the Supreme Court ruled on were brought by conservative activist Edward Blum and his group Students for Fair Admissions, which filed the lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of affirmative action policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2014, alleging they harm white and Asian American students.

On Thursday at the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Student Center East, student reaction was mixed.

“Affirmative action helps students who might have felt like, ‘Oh, maybe I shouldn’t go to college because it’s mainly white people.’ Or ‘Maybe I shouldn’t go to college because I won’t succeed,’” said Angel Alvarez, a pre-med incoming freshman studying neuroscience.

“Affirmative action provided that comfort, like maybe I do have a chance to be incorporated into a diverse program. UIC, for example, is one of the most diverse colleges. Affirmative action kind of provided that cushion for students who were on the fence of whether they went to college or not.”

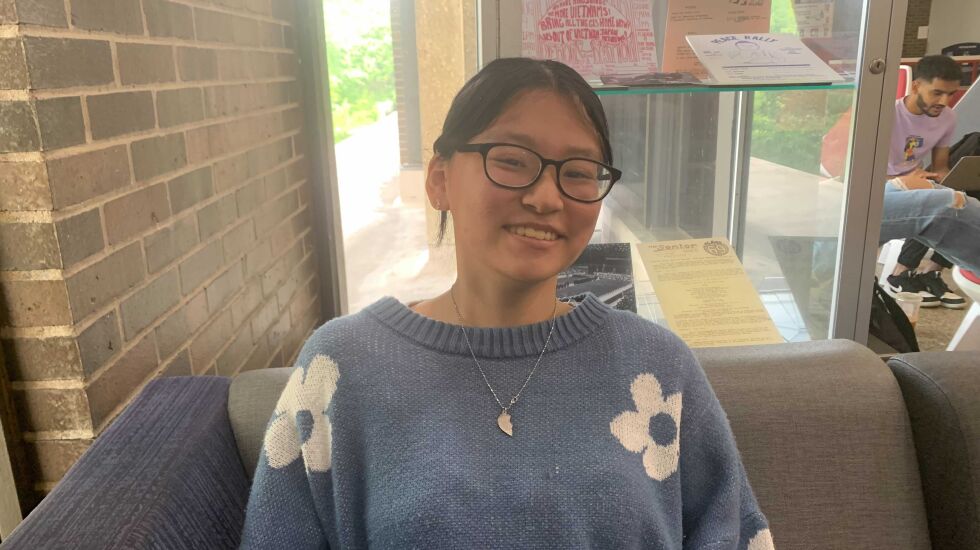

For students like Yu Lin, 18, of Schaumburg, a biochemistry major at UIC, the ruling stirred “conflicting feelings.”

“It’s kind of difficult for me to say, because I’m speaking about this as an East Asian and we’ve been taken as kind of a model minority,” said Lin of the stereotype that characterizes Asians as a hardworking, polite and law-abiding group that have achieved success due to a pull-yourself-by-the-bootstraps mentality.

While Lin said she sees both sides of the issue, she doesn’t think “affirmative action was directly the best choice to try to bridge these racial gaps between higher education because it also left out a lot of struggles faced by the model minority or white students who may come from lower income backgrounds.”

The decision may affect college admissions for students from large urban school systems like Chicago Public Schools, where 82% of children are Black or Hispanic.

The district is reviewing the decision and its potential impact on Chicago students but will continue operating initiatives that aim to support students of color in their pursuit of higher education, CPS spokeswoman Samantha Hart said.

The Illinois Board of Higher Education said the decision was “an attack on people of color, particularly Black people, who face discrimination through multiple facets of American society.”

“Affirmative action already was not a robust solution — it was merely a tool that intended to chip away at an enormous obstacle,” IBHE said in a statement. “It is disheartening to know that there are people intent on stifling racial equity at a time when we should all be working together to break down barriers because that is the right thing to do.”

The board said Illinois colleges and universities will keep “fighting to close equity gaps for Black, Latino, low-income, working adults and rural students,” and that work will “continue unabated because diverse and inclusive campuses and student bodies are critical to developing a well-rounded understanding of the world we live in and those with whom we share it.”

Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker said the state will “continue to uplift our students of color” by expanding higher education funding and scholarships for students from low-income backgrounds, the governor said.