Come to Stalker: Shadow Of Chernobyl fresh from a younger open-world series and it may appear deliberately unfinished – an early access build that never made it to version 1.0. Set in a radioactive psychic hinterland based on the 1989 Chornobyl nuclear disaster, it's a work of unvarnished post-Soviet miserabilism, a resolutely fun-averse shooter consisting of dreary geography full of loveless mercenaries, ethereal deathtraps and malfunctioning guns. While badged as a horror game, it's more depressing than horrifying. And how much more miserable it seems in the context of games such as Horizon: Forbidden West, with their bright, exotic landscapes of smooth-swallow quests and conveniences, their magnetic mission loops, crunchy ability combos and syrupy insistence that the post-apocalypse is a place of possibility.

Stalker shares fixtures with these later games: it's both their ancestor and their baleful adversary. It has trading outposts, enemy camps, and replenishing loot caches, the rudiments of a Ubisoft worldbuilding playbook. It has maps and mini-maps, even a magic compass that points to your next objective. Its story carries you through curated mission spaces as you hunt down the mysterious Strelok, who apparently lurks somewhere at the heart of the Chornobyl exclusion zone. You'll prowl the corridors of sunken silos, eyes peeled for the glimmer of a flashlight on a wall, and on the streets of Pripyat, the wretched city of Oz at the end of this radioactive-yellow brick road. But Stalker doesn't link these elements together as fluidly and gratifyingly as the Far Cry series would. And while its landscape teems with NPCs and mutant animals, all swirling about and raiding each other at the behest of the much-trumpeted A-Life system, it doesn't offer a "living, breathing world" as much as one that refuses to die.

Back in time

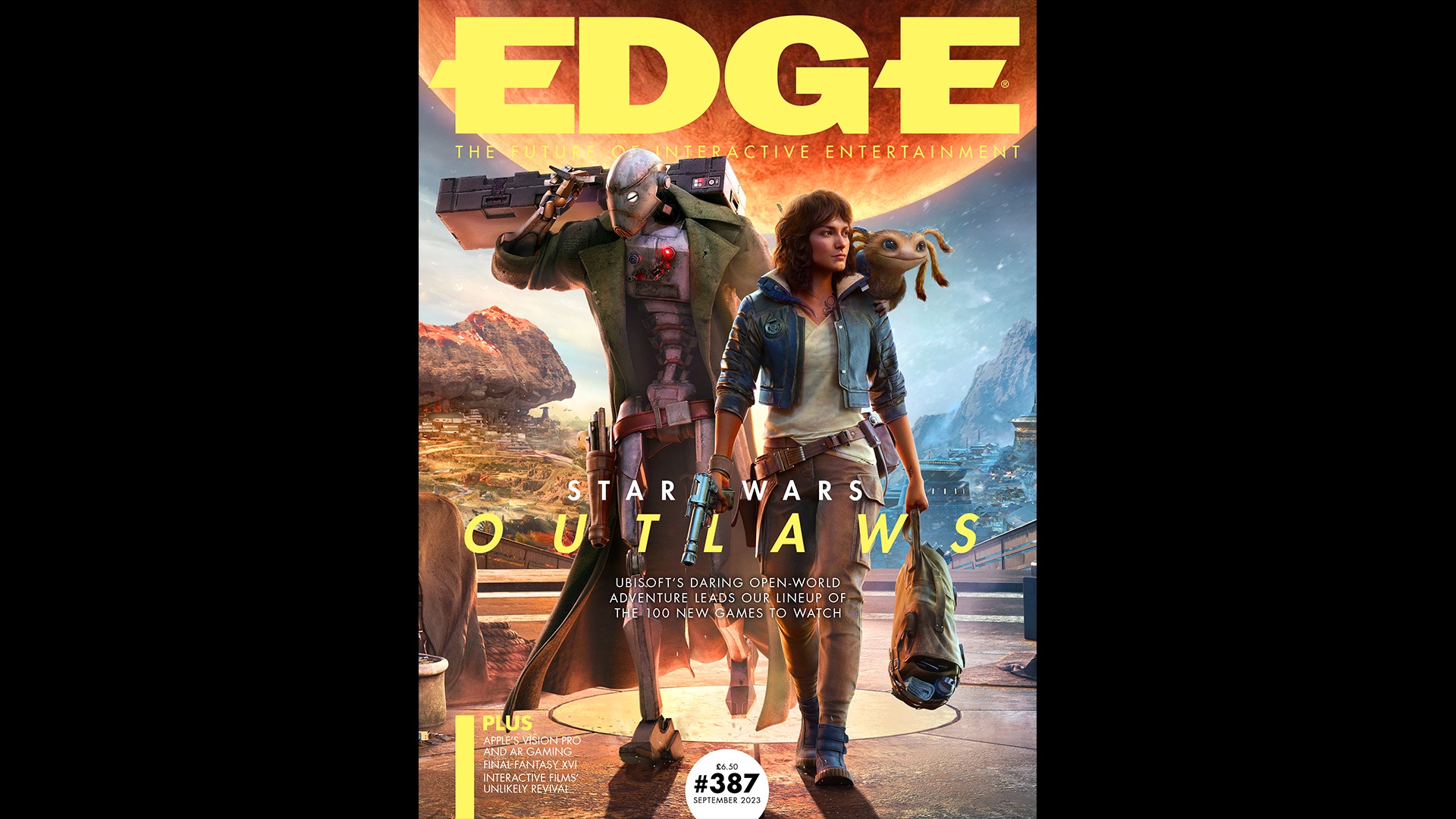

This feature originally appeared in Edge Magazine. For more fantastic in-depth interviews, features, reviews, and more delivered straight to your door or device, subscribe to Edge.

BGSC Game World's command of architectural detail is magnificent, given a morbid tolerance for shades of brown. Pripyat is an astonishing creation, a place of squares and rectangles that repeat from the soiled tiles and bricks of individual doorways to the corrugated skyline. The power station beyond is a masterful exercise in finding the balance between authentic recreation and tailored playspace, with girders and wire fences along its flank that provide thrillingly sparse cover against snipers and campers. But the majority of Stalker's landmarks are low and unpromising: artless chunks of concrete and rust, many already picked clean by rival Stalkers. You learn to avoid the buildings, which are often swamped in radiation that can only be fumbled around or powered through with a generous helping of anti-rads.

The world of Stalker never lures you towards its perimeter like the misty horizons of Fallout 3 – that vastly more optimistic and playful, even triumphal vision of nuclear disaster, which launched the year after. It mires you instead, bogging you down in the rubble and threatening you with the possibility of surprise attack from any angle. The surviving roads leave you visible for miles, and funnel you towards ambushers. The offroad stretches are awash with flickering spacetime disturbances that crush or electrify or incinerate anybody daring to travel as the crow flies.

The countryside, meanwhile, has no glamour to it, nothing like the neo-barbarian or Gothic sublimity we're trained to expect of post-apocalyptic settings. At its least inspiring, Stalker drops you into openly video gamey jumbles of hills, crates and unconvincing trees under skies of raw sewage, fringed by impassable fences. On your first runthrough, you'll often navigate by fumbling along these boundaries, secure in the knowledge that you won't be attacked from at least one direction. The settlements, if you can call them that, offer scant intimacy. They're checkpoints and resupply areas for lone wolves, each with his (there are no women in the Zone) heart set on the rewards that await in the power plant.

There's a certain bonhomie to your conversations with other Stalkers at campfires, for whom you can do favours such as chasing off packs of mutant boars. You can also hire some of them as allies, but these are working partnerships at best, with few named faces to give the game a sense of society. The idea of building communities in a radioactive wasteland is, after all, a farce.

The active threats are at once murky and diffuse and grubbily mundane. There are mutant humans and animals, who are rarely scary but always a handful, especially the invisible ghouls who corner you underground, anticipating the water walkers of Amnesia: The Dark Descent. But the game's nastiest antagonists are just rival dudes in masks and fatigues – malevolent smudges on the geography, shooting you through gaps in gutted train cars and ripped piping. They flank, advance and retreat in a leaden, undramatic way. Unlike, say, the cackling Locusts of Stalker's contemporary Gears Of War, they don't feel like they exist to entertain you, and they reserve no special regard for you next to rival factions and the wildlife. The weapons, meanwhile, aren't vintage long irons or kooky atompunk improvisations. They are by and large ordinary guns of recent manufacture, rapidly aged by overuse and the Zone's supernatural weather, passed around within a small population of warring pillagers.

Novel ideas

If you're reading this and asking why you'd play Stalker today, the answer begins with how it teaches you to think about exploration. Today's open worlds are often far larger than Stalker's cluster of open-ended levels, but they feel smaller for how they draw and direct your attention, their objectives, cues, routes and landmarks arranged so that even the longest journey becomes a series of distractions. They are designed to reel you between waypoints. Stalker makes you stop and consider the earth underfoot, and is all the vaster for it. The absence of fast travel means you'll trek back and forth through areas, experiencing their layouts from several angles, at different times of day, and with different enemy configurations, thanks to the A-Life system. The abundance of half-visible or invisible terrain hazards obliges a meandering approach, navigating by feel rather than sight: you learn to strafe around anything halfway intriguing, listening for the crackle and whine of your various detectors.

This circuitousness breeds a forlorn quietude that couldn't be further from the hungry manner in which we move through many better-known video game environments. It's the part of Stalker that feels most like Andrei Tarkovsky's 1979 film Stalker (both film and game are based on Arkady & Boris Strugatsky's novel Roadside Picnic). The film transports you to a dreamy purgatory of localised occult hazards which feel more like subversions of dramatic structure and cinematography than minefields. Characters travel cautiously across and around the perspective, rather than proceeding toward the vanishing point, dragging out each scene and so layering up the fear and wonder of the wilderness backdrop. In Stalker this idea is handled more reductively. Its anomalies are more akin to explosive oil drums, and a source of supernatural relics that are used to enhance your stats. But weaving in among them takes the same patience, cultivating a similar appreciation.

"In Stalker this idea is handled more reductively. Its anomalies are more akin to explosive oil drums, and a source of supernatural relics that are used to enhance your stats. But weaving in among them takes the same patience, cultivating a similar appreciation."

Though undersung in comparison to Assassin's Creed or Skyrim, Stalker's influence on other games is considerable. You see it most obviously in the parade of Stalker-likes, some developed by other eastern European teams, from The Farm 51's Chernobylite to Big Robot's The Signal From Tölva. The standout imitators are 4A's Metro games, though these are just as much a departure for how they rig Half Life-style levels to Moscow's railways. You can glimpse Stalker, too, in blighted multiplayer survival games such as Hunt: Showdown and in the battle royale genre, which tasks players with gunning to the heart of a hostile environment. Other teams have discarded Stalker's gunplay, the better to savour its geography and architecture – there are flashes of that wasteland ambience in many so-called walking sims, especially those set in abandoned spaces, such as The Town Of Light.

But perhaps Stalker's greatest legacy is the rediscovery of the real-life Chornobyl exclusion zone as a 'dark tourism' hotspot. GSC Game World's creation isn't the first or only contributor to popular interest in the site of the 1989 reactor explosion, but Stalker veterans are prominent alongside the Fallout players and fans of the 2019 HBO TV series who have visited Chornobyl – sometimes as part of guided package tours, sometimes by sneaking under the fence and hiking through the wilds, dosimeter in hand. Prior to Russia's 2022 invasion, the Ukrainian government had planned to redevelop the zone into an official attraction. While long contained, this calamity has the potential to spread, not least thanks to unwary visitors. Russian troops kicked up radioactive dust during their assault on the facility, and according to the Ukrainian state some have taken irradiated souvenirs to flog online.

All of which justifies Stalker's grim view of humanity. We wouldn't be surprised to meet in-game fans of the game touring the Chornobyl of GSC's forthcoming Stalker 2: Heart Of Chornobyl. This isn't really a 'post-apocalyptic' story at all. The disaster it's based on is unfinished and unfolding, in part because people refuse to let it lie. Its wasteland is a portrayal not of aftermath but of a catastrophe that threatens to expand outward into the pre-apocalyptic world, a deathly pocket universe kept active by that most fatal of compulsions: curiosity.

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine issue 387. For more fantastic features, you can subscribe to Edge right here or pick up a single issue today.