That renters have poorer mental health than home owners is well-documented. But how much of this is due to being in rental accommodation itself, rather than other factors such as lower incomes?

Our research quantifies this, showing housing insecurity has a clear impost on renters’ mental health. The good news is our results show the gap between renters and home owners can be closed through longer rental tenure.

Controlling for other factors, once renters have lived in the same property for six years, their mental health is, on average, the same as homeowners.

This shows the importance of a sense of stability and continuity to personal well-being. Policies to promote stable housing are therefore an essential part of efforts to tackle our mental health crisis.

How we did our research

Age, relationship status, income and preexisting health conditions all help to explain the significant difference in mental health between owner-occupiers, private renters and those in social housing.

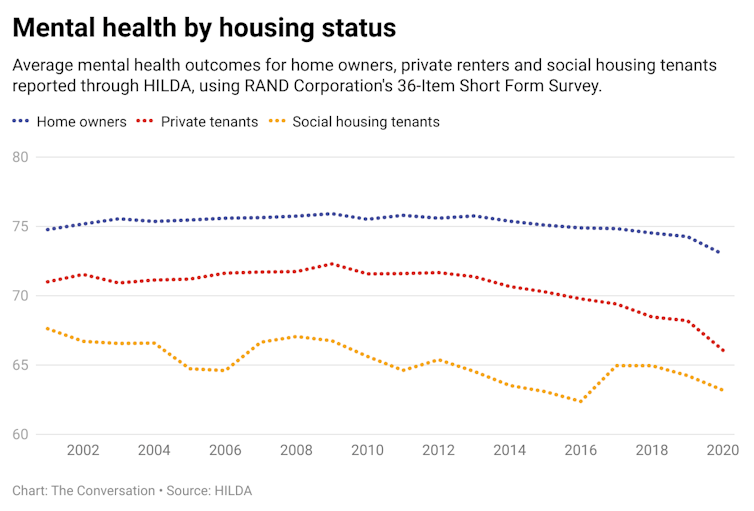

This is shown in the following graph, tracking the average mental health outcomes for owner occupiers, private rental tenants and social housing tenants in Australia over the past two decades.

This data comes from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, a nationally representative sample of about 18,000 Australians every year. It is a longitudinal study, meaning it surveys the same people each year on things including income, employment, housing, health and well-being. This enables researchers to use it to understand influences that change people’s lives over time.

HILDA enables mental health outcomes to be quantified and compared using two well-established scales.

One is known as the 36-item Short Form Survey (SF-36). This include questions about anxiety, depression, and loss of behavioural or emotional control. The other is the Kessler Psychological Distress scale questionnaire (K10). This asks questions about levels of nervousness, agitation, psychological fatigue and depression.

Read more: Poor housing leaves its mark on our mental health for years to come

We used both scales to measure the effects of tenure stability – being stably housed without frequent forced moves – to ensure the validity of our results.

Our analysis focused on working aged people (25-65 years of age) living in low to middle income households, using a final sample of 7,060 people.

We then created comparable groups of owners and renters by matching people by their health and sociodemographic (income, education, employment, age, household characteristics, etc). This allowed us to control for other factors affecting mental health and isolate the effect of tenure stability.

What we found

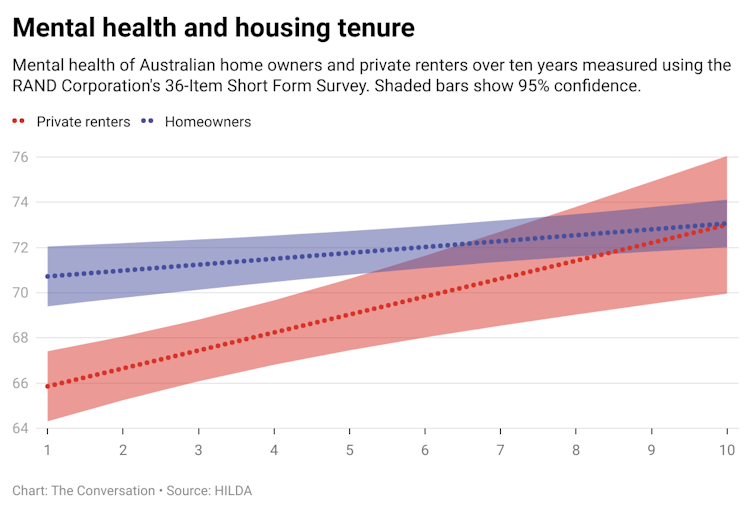

Our results show the mental health gap between private renters and home owners is greatest in the first year and declines the longer someone lives in the same home.

The next graph shows the results from the SF-36 mental health scale. The shaded bars indicates the range of values that we can be 95% confident will contain the true value. The dotted lines show average predicted values of mental health outcomes.

By the sixth year the difference between home owners and renters is slight and statistically insignificant.

It’s important to not interpret this as suggesting that renters will have better mental health after ten years. We don’t know that. There is less data available to make confident predictions after a decade.

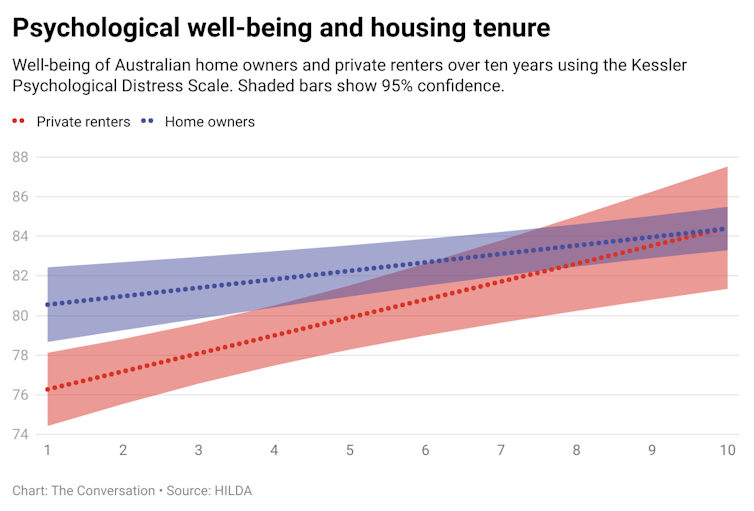

The next graph shows our results using the Kessler scale of psychological well-being. These results are slightly different but broadly consistent with the previous chart.

These results suggest home ownership itself is not essential to mental health of well-being. The more important factor is security and stability.

Studies overseas have found similar results. A 2019 study covering 25 European countries, for example, found that while homeowners tend to have better health and well-being outcomes than renters, the smaller the difference in outcome the smaller the tenure gap.

This may be due to stable tenancy increasing people’s sense of control and safety, enabling social connection and community participation, and benefits for childhood development.

This is likely why our research shows stability is particularly beneficial for private renters in the 35-44 age bracket – the cohort most likely to have young children. Their improvement with stability is larger than renters in other age groups and they become similar to homeowners in the level of well-being faster, reaching parity at three to four years.

Read more: Private renters are doing it tough in outer suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne

Stronger rental protection is needed

With the high costs of housing in Australia meaning an increasing proportion of the population are being shut out of home ownership, our results point to the importance of stronger tenant rights and improved minimum standards for rental housing conditions.

Most renters have little security, with lease length in Australia typically lasting one year, sometimes just six months.

One reform to give renters more security is to end no-grounds eviction – by which landlords can evict tenants on a fixed-term lease if they wish. The Victorian government did so in 2021. Queensland will do so in October. The other states and territories should follow suit.

Ending the merry-go-round of short, unstable leases means people can live better, healthier lives. That’s good not just for renters but society.

Ang Li receives funding from the University of Melbourne Early Career Researcher Grant Scheme and funding support from the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Emma Baker receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC), the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), and The Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI). She is currently board member of Habitat for Humanity (SA).

Rebecca Bentley receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.