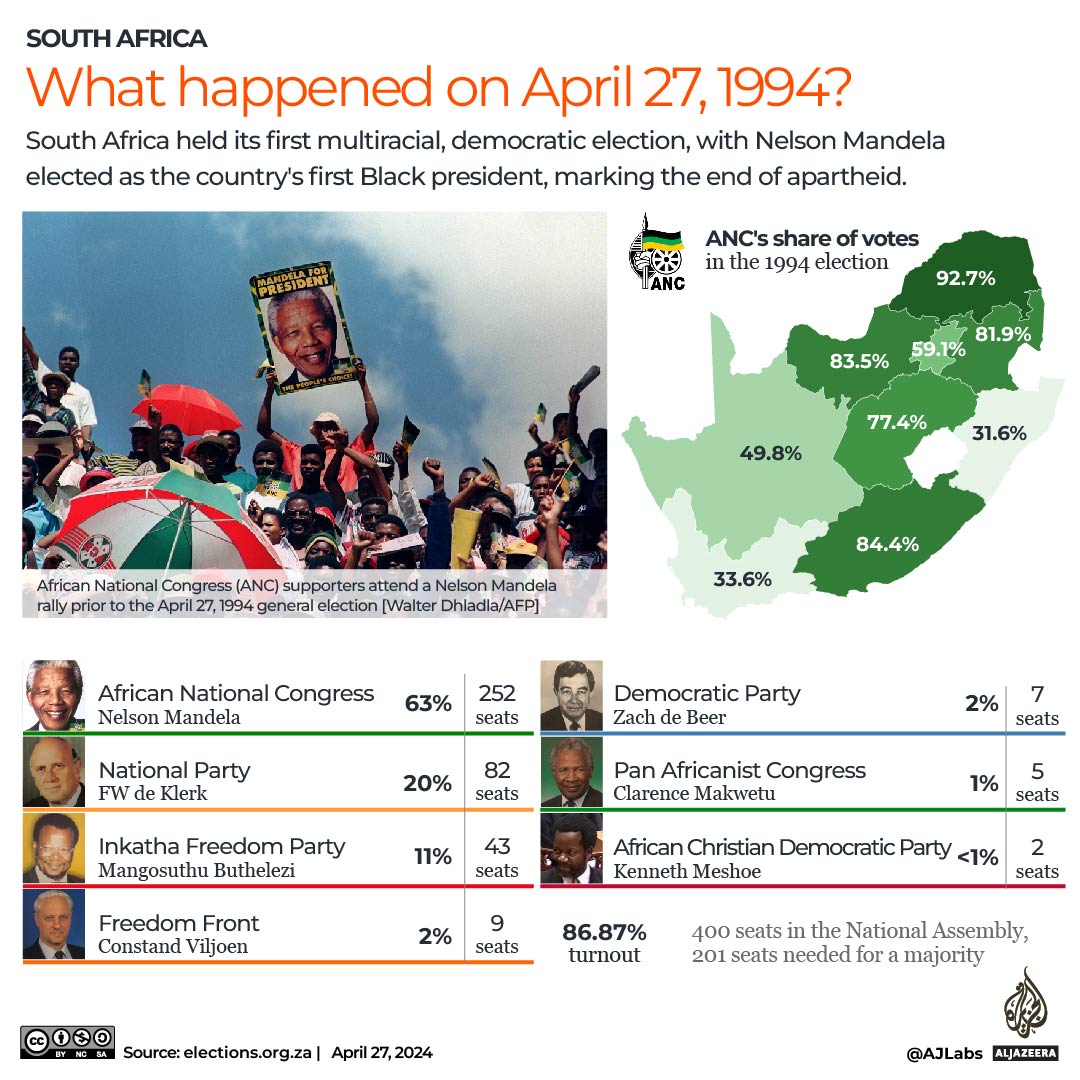

Three decades ago, on April 27, 1994, after centuries of white rule, Black South Africans voted in general elections for the first time. This marked the official end of apartheid rule, cemented days later when Nelson Mandela was sworn in as the country’s first Black president.

Since the arrival of Dutch settlers in the 1600s and British colonists in the 1700s and 1800s, South Africa had been a project that subjected Black people to systematically segregationist laws and practices.

But it was the adoption of apartheid in 1948 that codified and formalised these racist practices into law. It strictly separated people into separate classes based on their skin colour, putting the white minority in the highest class, with all others, including Black, Indigenous, multi-race people, and descendants of indentured Indian workers, below them.

South Africa’s road to freedom was long and bloody – laden with the bodies of thousands of Black activists and students who dared to protest, both loudly and quietly.

The wounds of those times are still painful and visible. Black South Africans make up 81 percent of the 60 million population. But, burdened with the trauma and lingering inequalities of the past, Black communities continue to be disproportionately afflicted with poverty.

Here’s how apartheid unfolded, how it collapsed, and what has since changed in South Africa:

What was apartheid?

The Afrikaner National Party (NP) government formally codified apartheid as government policy in South Africa in 1948.

Translated from Afrikaans – a language first spoken by Dutch and German settlers – apartheid means “apart-hood” or “separateness”, and its name embodied the ways the ruling white minority sought to separate itself from, and rule over, non-white people socially and spatially.

The policies rigidly and forcefully separated South Africa’s diverse racial groups into strata: White, Coloured (multiracial), Indian, and Black. These groups had to live and develop separately – and grossly unequally – such that although they lived in the same country, it was largely impossible for any one group to mix with another.

The rules were debilitating particularly for the Black majority who were relegated to the bottom rung. Laws limited their movement and squeezed them into small sections of land. The places they were allowed to inhabit were generally impoverished and included designated “Bantustans” (rural homelands) or townships on the outskirts of cities – settlements largely built out of ramshackle corrugated iron homes that were unplanned, overcrowded and had few to no amenities.

Meanwhile, the minority white population reaped the benefits of a gold-and-diamond-powered economy and flagrantly underpaid non-white labour as it kept the lion’s share of land, resources and amenities for themselves.

Apartheid also affected Indians, at first brought into South Africa as indentured labourers and later as traders, and multiracial people, called the Coloured community, who faced segregation and discrimination but to a lesser degree than Black Africans.

What were the apartheid laws?

Apartheid was enforced through a system of strict laws that kept everything in its place. There were “Grand” laws dictating housing and employment allocations, and “Petty” laws dealing with rules of everyday life, like the racial separations in public amenities.

Some of the most important laws were:

- Where people lived: The Group Areas Act – People were legally segregated based on race and allocated separate areas to live and work in. The law relegated nonwhite groups further away from developed urban cities. Black people, in particular, were housed in under-resourced fringe townships far from the centre. From the late 1950s, some 3.5 million Black South Africans were forced to relocate from urban areas, and some 70 percent of the population was squeezed into 13 percent of the country’s most unproductive land. Those who opposed the laws and refused to move had their homes forcibly demolished and were sometimes arrested and imprisoned. Black people, specifically men, who worked in cities as a source of cheap labour were required to carry “pass books” that dictated which white areas they were allowed to be in and for how long. Under the Separate Amenities Laws, public transport, parks, beaches, theatres, restaurants, and other amenities were segregated racially. Signs stating “Whites Only” and “Natives” were commonplace.

- What people learned: The Bantu Education Act – Apartheid laws stipulated the segregation of schools, including setting a different standard of education for different races. White schools were the best resourced, Coloured and Indian schools in the middle, while Black Africans were intentionally given an inferior education, specifically meant to ready them for manual labour and more menial jobs. A later law also segregated tertiary education. Some universities allowed non-white students to study but only to a limited degree, as apartheid officials sought to intentionally underskill the population. Government spending on white institutions was far higher than those catering to other groups.

- Who people could marry: The Immorality Laws – While intermarriages between white and Black people were already illegal under a 1927 law, a revised version (PDF) criminalised marriage and intimate relationships between white people and all other groups. The penalty was up to five years imprisonment. Thousands of people were arrested for this during apartheid, with nearly 20,000 prosecuted.

Why did apartheid end?

Apartheid came to an end out of the need for the white minority to sustain itself, not because of a change of heart, noted Thula Simpson, a historian of apartheid at the University of Pretoria.

“There was nothing benevolent or voluntary about the retreat of the white government,” he told Al Jazeera. “It was because there was an internal criticism of apartheid, and people were basically saying, ‘In order to maintain white supremacy, you must maintain white survival.’”

Before apartheid finally yielded, it was placed under tremendous pressure, including by growing resistance among Black South Africans. Political groups like the African National Congress (ANC) led by Nelson Mandela, and the Pan African Congress (PAC), roused the population, instigating protests, peaceful and violent. These movements triggered deadly crackdowns by the apartheid government.

When, on March 21,1960, apartheid police officers opened fire on some 7,000 Black people protesting pass laws, killing 69 people and injuring 180 others in what is now known as the Sharpeville Massacre, the world noticed. International uproar and condemnation from the United Nations followed, even as Mandela was imprisoned and the ANC liberation movement and others like it were banned by the apartheid government.

The 1976 killing of hundreds of Soweto pupils protesting the compulsory use of Afrikaans in Black schools also drew a similar global reaction. June 16 still marks the African Union’s “Day of the African Child,” in remembrance of those killed in the Soweto Uprising.

Increasingly, South Africa became isolated as it was slapped with economic sanctions, starting with a trade ban from Jamaica in 1959. The country was banned from sporting events, as well. By the 1990s, President FW de Klerk was forced to release Mandela and start negotiations for a democratic transition.

What’s changed since apartheid?

Legally and politically, much has changed in South Africa, with people of all races now free and equal under the law. Anyone is technically able to live, work and study anywhere, and people are free to interact and marry across colour lines. Black South Africans have democratically governed through the ANC for the past 30 years, compared with during apartheid when it was illegal for a Black person to even vote.

However, despite the significant gains, the legacy of apartheid is still present economically and spatially, which has contributed to South Africa being one of the least equal countries in the world.

Economy

Although South Africa’s economy grew with the end of apartheid and international sanctions, Black South Africans households continue to receive only a small share.

In the first decade after apartheid, the ANC-led South Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) went from $153bn in 1994 to $458bn in 2011, according to the World Bank.

However, a cocktail of corruption and government inefficiency has seen economic growth taper off, with gross debt rising from 23.6 percent of GDP in 2008 to 71.1 percent in 2022, according to researchers at Harvard (PDF).

While infrastructure quality has declined in general – partly due to the crumbling of the coal-powered electricity system that provided cheap power for production – it is exacerbating the historical inequalities Black communities face, experts said.

“The whole network has not been maintained so now the collapse is spreading out [even] to areas where it was not the norm,” Simpson of Pretoria University said, referencing South Africa’s recent, but frequent power and water cuts. “That impacts first and foremost the poor people,” he added.

In 2022, the World Bank classified (PDF) South Africa as the most unequal country in the world, and listed race, the legacy of apartheid, a missing middle class and highly unequal land ownership, as the major drivers. About 10 percent of the population controls 80 percent of the wealth, its report said.

Researchers from Spain’s Universidad de Vigo in 2014 found (PDF) that the average monthly income of Black South African households was 10,554 rand ($552), compared with 117,249 rand ($6,138) in white households.

In 2017, a government survey tracking household expenditure echoed those findings, stating that nearly half of all Black-headed households were spending the least while only 11 percent were in the highest spending category.

Economic woes have added pressure on the ANC, which is predicted to lose a parliamentary majority in the upcoming May elections for the first time since 1994. Simpson said a divide between older voters who witnessed the ANC’s struggle to end apartheid and younger people who do not have an attachment to the party has widened.

Education and skilled employment

After apartheid collapsed, historically white schools with good amenities and qualified teachers were desegregated and drew ambitious parents from Black communities, where government schools were poorly funded and lacked amenities like toilets – conditions that have persisted. According to a 2020 Amnesty International report, out of 23,471 public schools, 20,071 had no laboratory, 18,019 had no library, and 16,897 had no internet.

However, there is persistent trouble with transport to these formerly white-only schools for pupils from low-income and rural communities as these areas remain far apart and are not easily accessible. Pupils have also complained of racism in the formerly segregated white schools.

Meanwhile, general unemployment in South Africa is at more than 33 percent – one of the world’s highest. Nearly 40 percent of Black South Africans were unemployed in the first three months of 2023, while that rate was 7.5 percent among white people, according to government figures (PDF).

Where Black people make up 80 percent of the employable population (PDF) and account for 16.9 percent of top management jobs, white people who comprise about 8 percent of the employable population hold 62.9 percent of top management jobs.

A new law aimed at seeing more Black people employed – the Employment Equity Amendment Bill of 2020 – was signed last year by President Cyril Ramaphosa, but it sparked debate, with South Africa’s main opposition party the Democratic Alliance (DA) saying the law prescribes “race quotas” for companies and would cause other groups to lose jobs.

Housing

Although Black South Africans are no longer confined to rural, fringe townships – and people of colour spread out to urban areas across the country at the end of white minority rule – many still live in settlements with limited amenities.

In the once-majority-white Cape Town, for example, the population of Black South Africans increased from 25 percent in 1996 to 43 percent in 2016, according to the Center for Sustainable Cities (PDF).

“There’s been a massive redistribution of the population and whites have moved to the suburbs or outside the country,” Simpson said. “It has created the opportunity for Black South Africans to move closer to business districts.”

But, the historian added, “the townships remain the areas that have not been de-racialised.”

In some parts, small buffers separate Black townships from high-income neighbourhoods, providing starkly visible differences in satellite images. For example, a quick Google Maps tour will reveal the beautiful Strand, a seaside community in the Western Cape province that boasts of big homes with large, well-tended yards, and clean streets. Just beside it though, the Nomzamo township stands, with tinier homes and streets littered with refuse.

Raesetje Sefala, a researcher at the Distributed AI Research Institute (DAIR), said her organisation has observed that townships are still expanding. “They continue to resemble their appearance during the apartheid era, indicating that similar small land sizes are still being allocated,” she told Al Jazeera.

Sefala said the South African government now groups townships together with well-serviced suburbs as “formal residential neighbourhoods”, which makes it difficult for researchers to track the actual improvements in quality of life since the end of apartheid.

However, as someone who comes from a township, “I can attest to the extent of the poor service delivery,” she added.

Government reforms have sought to provide subsidised homes for low-income earners, with some four million homes (PDF) delivered since 1994 according to the South Africa Human Rights Commission. But some of those policies have meant houses are located far from economic centres, inadvertently recreating the same apartheid dynamic, some researchers have said.

Besides, there is a national backlog of some 2.3 million households and individuals still waiting for a home since 1994.

Meanwhile, rural homelands, where Black people were once forced to reside, continue to be at a disadvantage. For one, they experience extremely low employment rates: Although some 29 percent of South Africa’s population lives there, employment rates are roughly half of what they are in all other parts of the country according to Harvard researchers. Experts have blamed the government’s failures to expand connecting infrastructure like transport, technology, and know-how to these historically excluded places.