New Zealand plans to commission about eight gigawatts of solar photovoltaic projects – more than the maximum power demand of the whole country on a typical winter’s day – by 2028, according to the government’s latest generation investment survey.

Eight of these solar farms are already operational and spread across the country. More than 40 are in various stages of development, with the construction of the largest single project, in excess of 150 megawatts, due to start this year.

Solar farms are not without challenges, though. They can use up farmland and change the rural landscape. However, we argue that more efficient farms can integrate solar panels and agricultural production, with economic benefits for farmers.

Given Aotearoa New Zealand’s current solar generation capacity of just under ten gigawatts, the increased generation is a significant development in the electricity sector and a positive contribution to the 2030 target of 100% electricity generation from renewables.

However, opposition has focused on the potential changes to the rural landscape and the use of productive soils.

This is especially because solar farms are likely to be proposed for fast-track consenting. Infrastructure Minister Chris Bishop has signalled the process will “make it easier to consent new infrastructure, including renewable energy”.

We advocate a suitable option for New Zealand lies in “agrivoltaics” – using agricultural land for both renewable electricity generation and farming.

Addressing concerns over land-use change

In a country where half of its area serves agricultural purposes, land-use change is an obvious concern. The answer may well be agrivoltaics, which is gaining traction globally.

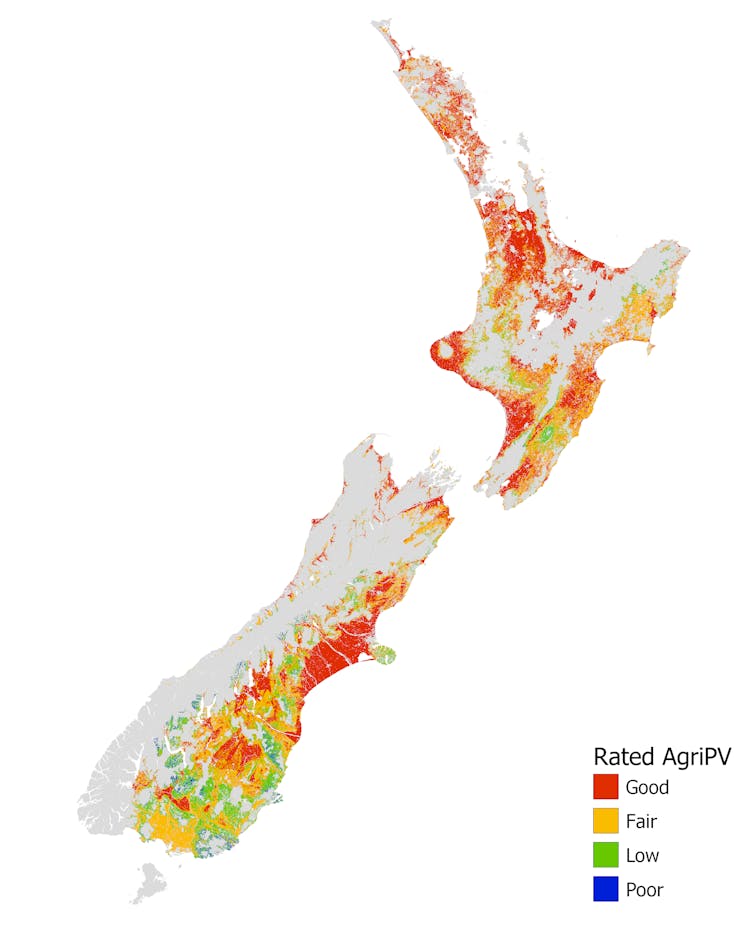

It means using rural land for both electricity generation and agriculture (including horticulture). Large areas of the country have been shown to be suitable for this dual land-use approach.

The major benefit of agrivoltaics is the micro-climate created under the solar arrays, with cooler temperatures during warm days and warmer temperatures at night. This results in less heat stress and less frost damage for crops.

Soils also retain more moisture, which means certain crops grow better, even with more shading. Pastoral production has seen the greatest benefits globally because animals are better protected from the elements, need less water and can access pasture in dry conditions.

Solar grazing

The integration of solar arrays with sheep farming is a major opportunity for New Zealand. Indeed, it is common practice to utilise sheep to maintain vegetation between and underneath the solar panels. This is a growing business in its own right, known as solar grazing.

The economics are quite compelling. A case study on a Canterbury farm shows the profitability of the solar assets with an additional revenue stream for the farmer from leasing agreements.

Given the economic worries sheep farmers are facing, this should be a definite consideration.

Addressing the hurdles

There are hurdles to realising this opportunity in a just manner. One is the upgrading of the grid to accommodate new generation capacity, estimated to cost NZ $1.4 billion a year until 2030. This figure is largely associated with the required high-voltage transmission network.

Transpower’s net zero grid pathways programme aims to address this issue. However, many of the smaller utility-scale solar assets will be connected to low-voltage distribution networks, which will be a significant constraint.

None of this required infrastructure upgrade is included in the 2024 budget. Lines companies are left to manage this issue. Effectively it means that not all farmers will be able to capitalise on the opportunity. It will be a case of “first come, first served” and a potential gold rush.

Consenting issues

This plays into the reforms of the Resource Management Act currently underway. The Fast-track Approvals Bill is currently going through the select committee and may limit comprehensive consultation with stakeholders and the careful consideration of any implications of solar projects.

A recent notification decision by the South Wairarapa District Council, for example, concluded that a proposed solar farm

is inconsistent with the other activities taking place in the rural (primary production) zone, and as such the amenity values of the rural environment would be adversely impacted.

Conversely, in the context of an application for a solar farm in Selwyn, a decision-making commissioner observed that our resource management system allows for, and even expects, changes in land use.

Whether changes are permissible depends on […] the planning [documents], the consideration of environmental effects and […] balanced judgement as to whether the changes meet the legislative and other requirements.

New Zealand’s national policy statement for renewable electricity generation acknowledges competing values associated with the development of renewable energy resources. But it does not identify how to resolve any conflict.

The protection of highly productive agricultural land is covered by the 2022 national policy statement for highly productive land, and planning officials may view conventional solar farms to be in conflict. We argue that well-designed agrivoltaic systems will resolve this conundrum.

Indeed, the decision-making panel in one agrivoltaic application in the Waikato commented that:

its members have seldom observed a project that delivers such significant benefits with such comparatively few adverse effects.

We would like to acknowledge the contribution Olivia Grainger and Anna Vaughan made to this research.

Alan Brent has received an internal grant (#410699) from Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington and funding from the Aotearoa New Zealand Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment Our Land and Water (Toitū te Whenua, Toiora te Wai) National Science Challenge (contract C10X1901) to support the research that informs this article.

Catherine Iorns does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.