Under your feet lies the most biodiverse habitat on Earth. The soil on which we walk supports the majority of life on the planet. Without the life in it, it wouldn’t be soil. Unfortunately, Australia’s soils are not in good shape. The new State of the Environment report rates our soils as “poor” and “deteriorating”.

We’re all familiar with some soil dwellers, such as earthworms. But the lion’s share of life underneath is invisible to the naked eye. Microbiota like bacteria, nematodes, and fungi play vital roles in our environment. These tiny lifeforms break down dead leaves and organic matter, they cycle nutrients, carbon and water. Without them, ecosystems would collapse. Amazingly, most of this wealth of life is unknown to science.

Australia has not undergone the same glacial or volcanic activity as other parts of the world. That’s left most of our soil old and infertile. Our soils are highly sensitive to human pressures, such as contamination, acidification and loss of organic carbon. When we remove communities of plants, this leads to soil erosion. Land clearing also hits underground life hard, causing microbial diversity to decline.

Soil’s lifeforms are also under immense pressure from agriculture, as well as climate change and urban expansion. If we include livestock, more than half of Australia is now being used for farming. If we can improve farming methods, we can bring back soil biodiversity – and use it to produce healthy crops.

Why does it matter if we lose soil microbial diversity?

Australia has many different soil types. Images of each state’s iconic soil demonstrates how much they can differ. Importantly, soils differ greatly in their ability to support industrial crop production. Much of Australia is not naturally suited to this.

Read more: Pay dirt: $200 million plan for Australia's degraded soil is a crucial turning point

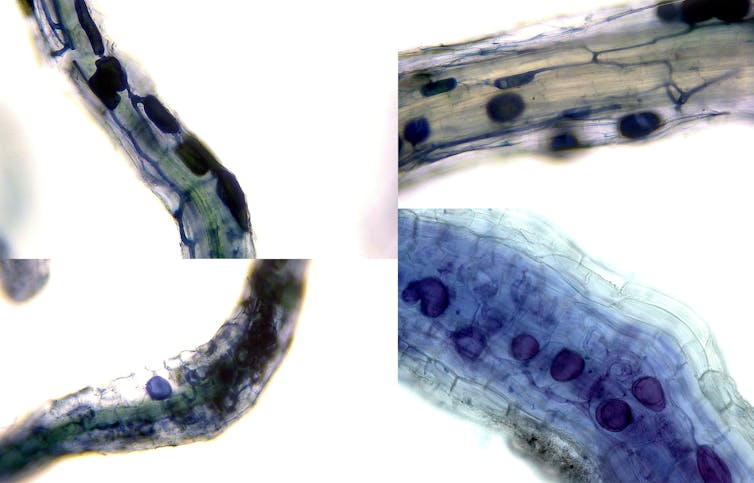

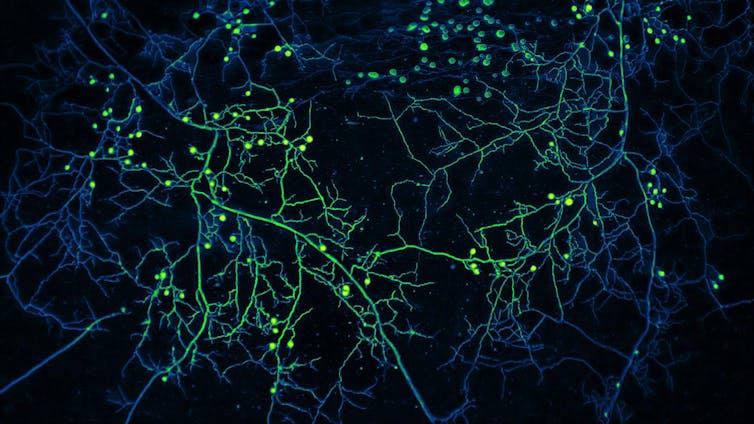

Some intensive farming methods like ploughing, irrigation and the use of fertilisers and pesticides are particularly damaging to the life in our soils. We know these practices reduce the abundance and diversity of a particularly important group of microorganisms, known as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. These fungi spread out into vast fungal networks below ground, and colonise the root systems of plants in a symbiotic relationship.

When you look at a field of corn or wheat, you might think all the action is above ground. But what happens in the soil is vital. The plants we rely on to survive rely in turn on strong relationships with these underground fungal networks.

Soil fungi can boost plant uptake of key resources like phosphorus and water and can even improve how plants resist pests. These fungi are also critical to the cycling of nutrients and carbon in our environment, and the networks they form give structure to soil. These relationships go back much further than humans do. Plants and fungi have been cooperating for hundreds of millions of years.

Despite breaking up this relationship in our agriculture, we have achieved ever-increasing yields.

That’s because most crop and pasture production relies on various fertilisers and pesticides for crop nutrition and pest control, rather than fungal networks or soil biology. The continued development of these fertilisers and pesticides have undoubtedly enhanced crop production and allowed millions of people to escape hunger and poverty.

The problem is, relying on pesticides and fertilisers is not sustainable. Many pesticides are under increasing restrictions or bans, and phosphorus fertiliser will only become more expensive as we deplete global phosphate reserves. Critically, their excessive use negatively impacts soil biology and the environment.

If we reduce the diversity of fungi in our soils, we lose the benefits they provide to healthy ecosystems – and to our crops. A soil with less biodiversity erodes more easily, loses its stored carbon quicker and causes disrupted nutrient cycles.

Can we protect our soil fungi?

Yes – if we change how we manage our soils. By working with our living soils rather than against them, we can meet increasing demand for food and keep farms economically viable.

As you might expect, organic and conservation farming is less damaging to soil fungi compared to conventional farming, due to their limited use of certain fertilisers and most pesticides.

These approaches also involve less ploughing or tilling of the soil, which lets fungal networks remain intact and so benefitting soil structure. This can promote plant protection from pests, and this soil biodiversity also keeps disease-causing microbes in check.

Clearly, changes to our agriculture can’t happen overnight. Sri Lanka’s sudden ban on synthetic fertilisers and pesticides in 2021 caused chaos in their farming sector and continues to threaten their food security. Widespread adoption of more sustainable farming techniques in Australia must be done gradually, with support and incentives from industry and government. But it will have to happen. The status quo can’t last, as our soils continue to deteriorate and fertilisers and pesticides become more expensive and unavailable.

To care for our soils, we need to know more about them

While we know the life permeating our soils is in trouble, we need to know more. One important finding from the State of the Environment report was the need for more data on the biology of our soil to aid sustainable land use.

Why? To date, most of our understanding of how farming impacts soil fungal diversity is based on overseas research. Despite the ecological importance of these microbiota and their potential to accelerate sustainable food production, we still don’t have a clear picture of what’s underneath our fields. For a start, we need to know what mycorrhizal fungi live where.

To overcome this challenge, we have launched Dig Up Dirt, a new nationwide research project designed to let us take stock of our beneficial soil fungi.

Farmers, land managers and citizen scientists can send us soil samples to allow us to map Australia’s networks of soil fungi. The data we collect will also be fed into the international efforts to map fungi globally.

This is a long-overdue step towards learning to work with soil fungi to benefit agriculture – while conserving the life below our feet.

Adam Frew receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Christina Birnbaum has received funding from Parks Victoria. She is a lead-convenor of the Ecological Society of Australia Plant-Soil Ecology Research Chapter.

Eleonora Egidi receives funding from the Australian Research Council

Meike Katharina Heuck receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.