On Sept. 4, 2022, Pope John Paul I, born Albino Luciani, will be beatified: proclaimed as “blessed,” the last step before being canonized as a Catholic saint.

Elected head of the Catholic Church in August 1978, he held the papacy for only one month. John Paul I was found dead in bed late that September. The cause of his unexpected death was determined to have been a heart attack, notwithstanding a lingering swirl of conspiracy theories.

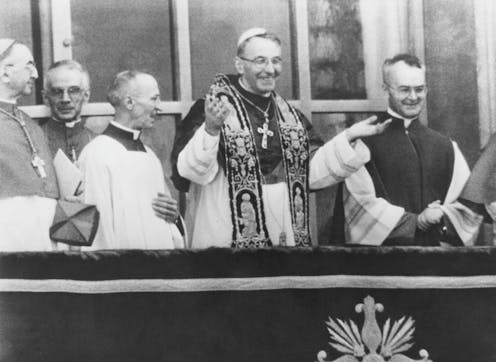

Despite his short papacy, John Paul I left a mark. Called the “Smiling Pope” because of his welcoming manner, he was the first pope in centuries to refuse a formal coronation, choosing a simpler inauguration ceremony. The new pope’s life as a priest, bishop, cardinal and finally pope was embodied in the motto he chose for his ministry: “humility.”

All of the past five popes who have died have been nominated for canonization, and three have been named saints. But not every pope has been revered as a saint by Roman Catholics – especially during the medieval era, a period I focus on in my work as a scholar of Catholicism.

From powerless to powerful

Nearly all the popes of Christianity’s first few centuries have been recognized as saints – starting with St. Peter, Jesus’ apostle, whom Roman Catholics recognize as the first pontiff. He and St. Paul, the author of several of the letters known as epistles in the New Testament, are both believed to have been executed in Rome around A.D. 64.

Until the early fourth century, Christianity was illegal in the Roman Empire, although this legislation was not always rigidly enforced. Tradition holds that most of the early popes died as martyrs.

After Christianity was legalized, bishops and popes became increasingly involved in the empire’s political struggles of the next several centuries. Some of these arose when the church became divided over important theological issues, and individual emperors supported one view over another.

Invasions by Germanic tribes from north of the Alps also caused chaos, and popes often served as stabilizing figures in Italy and beyond. Several popes from the sixth through eighth centuries have been named saints.

The age of scandal

During the early medieval period, after repeated political and military upheavals, the Frankish kings north of the Alps “donated” territories in parts of northern and central Italy to the pope. These Papal States governed directly by the pope became an important center of political activity.

The popes’ secular power led to struggles among aristocratic families of Rome for control of the papacy. This led to a period in the late ninth and 10th centuries often called the “Dark Ages” or “nadir” of the papacy.

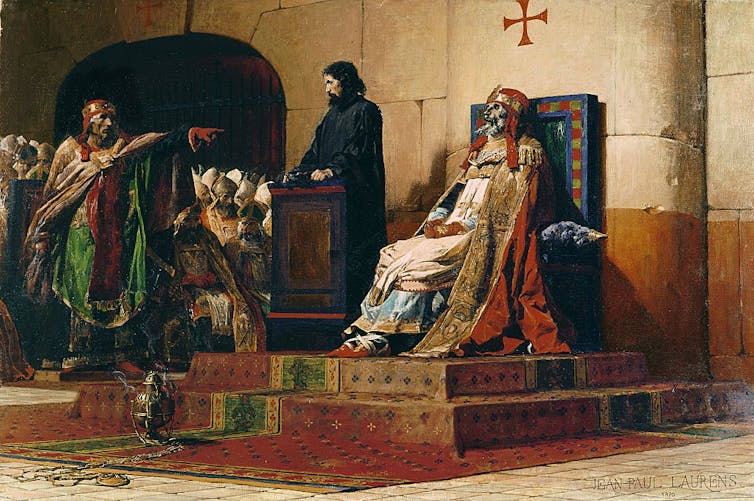

Most of the men chosen to be pope during this period were clearly unworthy of the position, and far fewer were canonized. Pope Stephen VI hated his predecessor, Pope Formosus, so deeply that he had the corpse dug up and put on trial at what came to be called the Cadaver Synod in 897. After the guilty verdict, he had the corpse thrown into the Tiber River. Soon after, he was himself assassinated.

Pope John XII, of a noble Tuscan family, was chosen to be pope as a very young man because of his political connections. He was derided at the time for his dissolute life and for having “turned the Vatican into a brothel.” Legend has it that in 964, he died while committing adultery with another noble’s wife.

Ironically, perhaps, it was during this era that popes became responsible for naming saints, and one of the Vatican offices was tasked with examining cases. Previously, groups of Christians venerated local individuals whom they considered especially holy, but apart from a declaration by the regional bishop, there was no formal process for proclaiming sainthood.

Renaissance rulers

The 14th century was an especially chaotic one for the papacy, with several popes living in Avignon, France, because of its kings’ political dominance. After Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome in 1377, the next papal election was disputed, and until 1417 there were two, then three, cardinals claiming to be the pope.

These disruptions led some popes of the late 15th and early 16th centuries to be even more focused on preserving their political power. The Papal States took their place among the increasingly wealthy and ambitious Italian city-states of the Renaissance.

Again, the reputation of some popes caused scandal. Rodrigo Borgia, reigning as Pope Alexander VI, named his own son a cardinal, conducted numerous affairs, and sent the papal armies into battle against other Italian families. One of his successors, Julius II, known as the “Warrior Pope,” actually donned armor to lead his own soldiers into battle to expand the Papal States.

No pope from this period would be canonized until Pope St. Pius V, a leader of the Catholic Reformation or Counter-Reformation of the later 16th century.

The modern process

In the 19th century, the area under papal control was reduced to the tiny city-state of Vatican City, which is recognized to this day as a sovereign state by much of the world, including the United States and the European Union. Since then, as popes’ most public roles have become more pastoral than political, more of them have been canonized.

Popes must meet the same requirements as any other Catholic proceeding toward sainthood, which include demonstrating a life of “heroic virtue” and typically having two miracles attributed to their intercession with God. Traditionally, Catholics had to wait 50 years after a death to nominate the person for sainthood. Today, the waiting period is just five years – and sometimes waived altogether.

Pope St. John Paul II, for example, died in 2005, was beatified in 2011 and canonized in 2014. Even at his funeral, many in the crowd were already calling for his immediate canonization. This “fast-track” decision has been criticized amid concerns about his handling of clerical sexual abuse reports during his long pontificate.

In John Paul I’s case, the Vatican proclaimed him a “Servant of God” in 2003, the first step in the process.

In 2017, after studying his life and his writings to confirm his “heroic virtue,” Vatican officials recommended that Pope Francis take the next step and proclaim John Paul I as “Venerable.”

Four years later, after a further review, Pope Francis recognized the recovery of a young Argentinian girl in “imminent” danger of death as a miracle attributed to the intercession of John Paul I. A miracle of this kind is normally required for a “venerable” to move to beatification, the next step toward canonization.

After the beatification in September, John Paul I will have the title “blessed,” and will be assigned a feast day that may be observed in regions where he once lived and worked.

In the future, if a second miracle is officially recognized, he may be canonized and proclaimed a saint. Either way, his case illustrates the contemporary Catholic Church’s view of canonization: No one, even a pope, becomes a saint automatically – but every Catholic whose life and actions demonstrate “extraordinary virtue,” famous pope or obscure layperson, may be proposed.

Joanne M. Pierce does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.