Two shocking, back-to-back instances of violence in Memphis, Tennessee, have Republican figures across the state and the country — and even some Democrats — calling for new policies to roll back parole and impose harsher sentences.

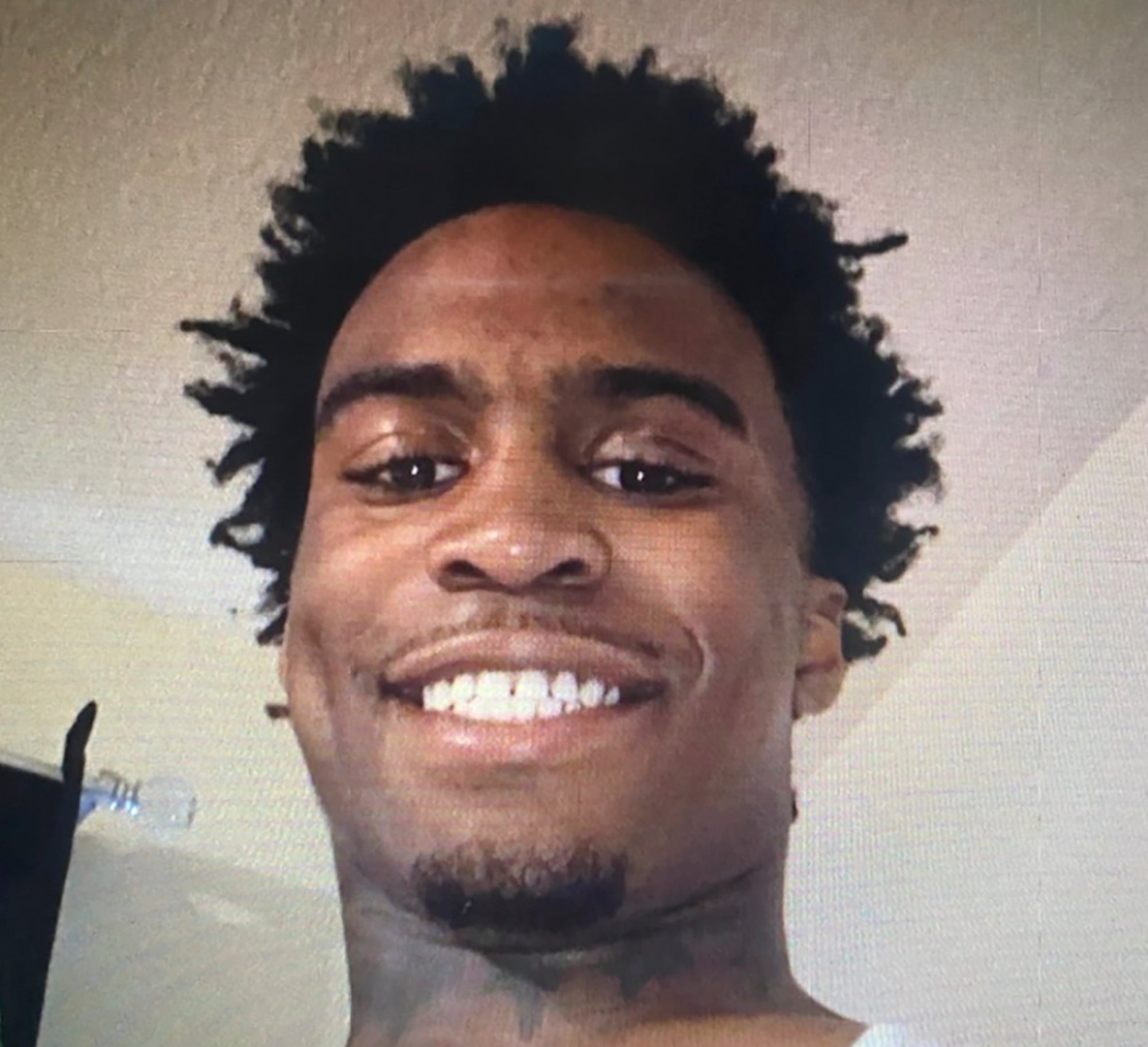

They argue such policies would’ve stopped Cleotha Abston, the 38-year-old accused of kidnapping and killing Memphis teacher Eliza Fletcher last week, and Ezekiel Kelly, who police say live streamed a shooting spree on Facebook on Wednesday that killed four and injured three.

Abston was released from prison in 2020, after serving 19 years of a 24-year sentence for kidnapping a Memphis attorney. Kelly got out of prison this March, after serving two years of a three-year sentence on aggravated assault.

"We want safe communities, safe streets. You shouldn’t be afraid to go out and run in the morning, you shouldn’t be afraid to let your kids walk home from school," Tennessee House Speaker Cameron Sexton, a Republican, said on Thursday.

After the Memphis shooting he lauded the state’s “truth in sentencing” law, which passed this spring and expanded the list of crimes that require people to serve 100 per cent of their sentence, while adding 20 other offences that now require 85 per cent time served. He’s called for new legislation in 2023 that would try juveniles as adults in some cases, and remove credit programmes that allow people people to redice their sentences with good behaviour in prison.

"You shouldn’t be afraid to pump gas. But we’ve had over the last two decades a criminal justice approach that has been put in place by these soft-on-crime groups that want to tell the criminal, ‘We care about how you feel, we don’t want you to do this,’” Speaker Sexton added.

Jim Strickland, the Democratic mayor of Memphis, similarly called for harsher parole rules after the violence.

“This is no way for us to live, and it is not acceptable,” he said on Wednesday, adding, “If Mr Kelly had served his full three-year sentence he would still be in prison today and four of our fellow citizens would still be alive”.

Kelly would’ve still been in prison under state law that has passed since he was first incarcerated.

Conservative media figures joined in the call for such harsher criminal justice policies.

“Democrat crime policies are wreaking havoc and getting countless people killed,” right-wing commentator Matt Walsh wrote on Twitter on Wednesday about the shooting. “Enough is enough.”

Similar conversations have happened in Canada, where suspected mass stabber Myles Sanderson had numerous past criminal convictions, but was released by Canadian parole officials.

"There will be an appropriate time and a place to review policy and resourcing and we need to embrace that review, we need to be transparent with Canadians to make sure that this kind of thing never happens again," public safety minister Marco Mendicino said on Thursday.

Not everyone is on board with this push for more parole. They cite the wide body of evidence that longer sentences don’t deter violent crime.

"We cannot let events from the last few days happen in such a way that it slows down a bit of progress," Tennessee Governor Bill Lee said this week. "Like I said before, Memphis is the soul of the state, and it’s hurting right now. But we are committed, we are with that community, and we are committed to making certain we address the issue of crime."

He praised programmes like the previous year’s budget, which invested $100m into evidence-based solutions, like community violence intervention programmes.

"We need to clearly be tough on crime, we cannot be soft on crime," Mr Lee added. "We can be smart on crime. And there’s a way to do both of those, and I think that’s what we will do going forward."

The truth in sentencing law passed without the governor’s support. He argued the bill would “result in more victims, higher recidivism, increased crime and prison overcrowding, all with an increased cost to taxpayers," at the time.

Criminal justice experts agree that simply ratcheting up sentences isn’t a means to better outcomes.

“The issue with truth in sentencing is that it eliminates the possibility that somebody might be prepared for release sooner and that all people sort of are corrected at a certain period of time, which is of course not true,” Ashley Nellis, a senior research analyst with The Sentencing Project, told The Associated Press. “People reform over different periods of time that fluctuate from person to person.”

Thomas Snow, executive director of the Tennessee Prison Outreach Ministry (TPOM), a faith-based group that provides rehabilitation services to incarcerated people and returning citizens in Nashville and Memphis, says he’s also a supporter of the promise of parole. He pointed The Independent towards a letter he sent to state officials when the truth in sentencing law was up for debate.

“While TPOM recognizes that serious crimes must be met with a serious response from the justice system, I would urge the Legislature to consider that prisons were originally designed to incarcerate and rehabilitate the guilty,” the letter wrote. “Diminishing the effort to rehabilitate can only reduce the motivation to change.”

“With the right encouragement, and with the hope of seeing the other side of the fence, Tennessee inmates will leap at the opportunity to improve,” he added.

The evidence backs this up.

Studies suggest that longer prison sentence have essentially zero effect on deterring violent crime.

An analysis of parolees in Michigan found that less than half a per cent of those convicted of homicide killed again.

In fact, the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics found in a sweeping study of those released from prison that people with violent offences are actually the least likely among major crime categories to be re-arrested within three years, though recidivism remains high overall.

“Laws and policies designed to deter crime by focusing mainly on increasing the severity of punishment are ineffective partly because criminals know little about the sanctions for specific crimes,” the federal National Institute of Justice wrote in a brief on sentencing. “More severe punishments do not ‘chasten’ individuals convicted of crimes, and prisons may exacerbate recidivism.