South Korea's government stressed Wednesday it will make its own decisions in strengthening its defenses against North Korean threats, rejecting Chinese calls that it continue the polices of Seoul’s previous government that refrained from adding more U.S. anti-missile batteries that are strongly opposed by Beijing.

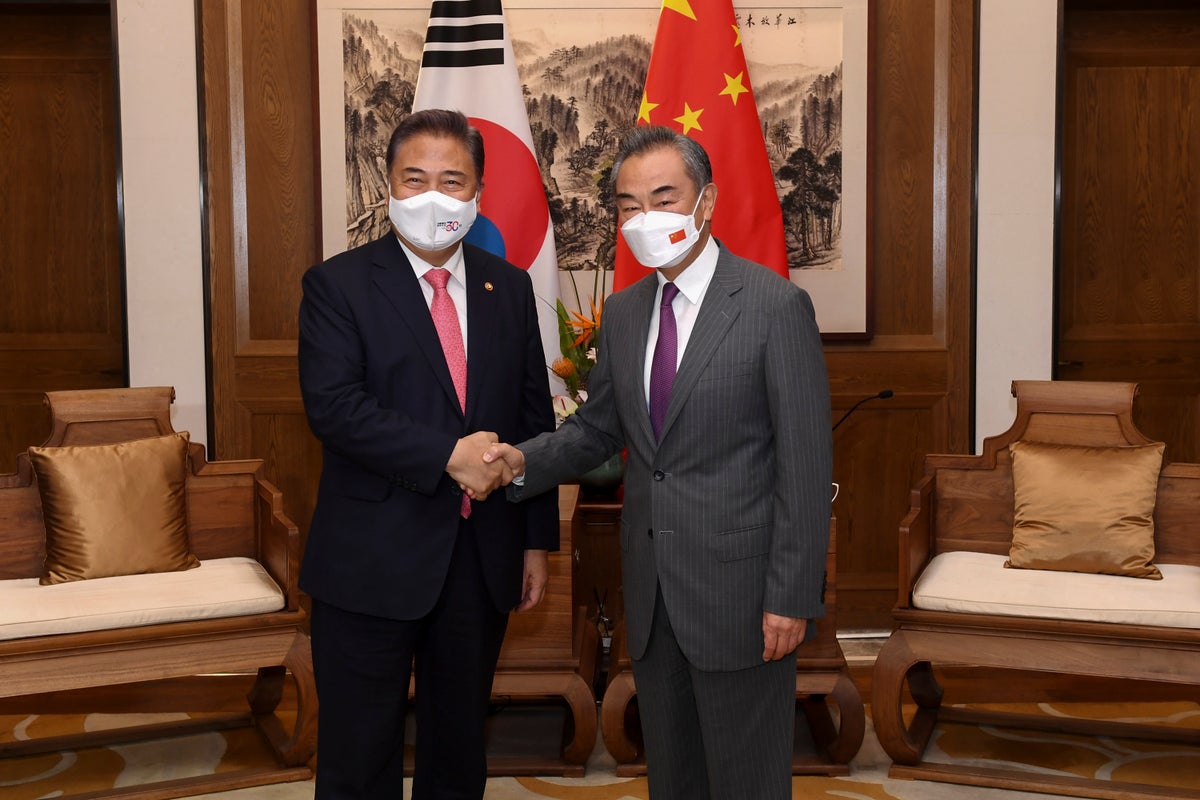

The differences between South Korea and China underscored a reemerging rift between the countries just a day after their top diplomats met in eastern China and expressed hope that the issue wouldn’t become a “stumbling stone” in relations.

Bilateral ties took a significant hit in 2017 when South Korea installed a missile battery employing the U.S. Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense system, or THAAD, in response to nuclear and missile threats from North Korea.

The decision drew an angry reaction from China, which said the anti-missile system could be reconfigured to peer into its territory. Beijing retaliated by suspending Chinese group tours to South Korea and obliterating the China business of South Korean supermarket giant Lotte, which had provided land for the missile system.

South Korea’s previous president, Moon Jae-in, a liberal who pursued engagement with North Korea, tried to repair relations with Beijing by pledging the “Three Nos” -– that Seoul wouldn’t deploy any additional THAAD systems, wouldn’t participate in U.S.-led missile defense networks and wouldn’t form a trilateral military alliance with Washington and Tokyo.

Moon’s dovish approach has been discarded by his conservative successor, Yoon Suk Yeol, who has vowed stronger security cooperation with Washington and expressed a willingness to acquire more THAAD batteries to counter accelerating North Korean efforts to expand its nuclear weapon and missile programs.

Commenting on Tuesday’s meeting between Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and his South Korean counterpart Park Jin, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin in a briefing Wednesday reaffirmed Beijing’s stance that the THAAD system in South Korea undermines its “strategic security interests.”

He added that Seoul had committed to a policy of “Three Nos and One Limit,” the latter apparently referring to a pledge to limit the operations of the THAAD battery already in place, something Seoul has never publicly acknowledged.

“The two foreign ministers had another in-depth exchange of views on the THAAD issue, making clear their respective positions and enhancing mutual understanding,” Wang said. He said the minsters agreed to “attach importance to each other’s legitimate concerns and to continue to handle and control the issue prudently” to prevent it from becoming a “stumbling stone” in bilateral relations.

South Korea’s Foreign Ministry said in a statement that it understands that Wang was referring to the policies of the Moon government with the “Three Nos and One Limit” remark.

It said the Yoon government has maintained that THAAD is a defensive tool for protecting South Korean lives and property and a national security matter that Seoul isn’t willing to negotiate with Beijing. It also insisted that the “Three Nos” were never a formal agreement or promise.

“During the meeting, both sides confirmed their differences over the THAAD matter, but also agreed that the issue should not become an obstacle that influences relations between the countries,” the ministry said.

South Korea, a longtime U.S. ally, has struggled to strike a balance between the United States and the increasingly assertive foreign policy of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s government.

Deepening conflicts between Washington and Beijing over a broad range of issues including Taiwan, Hong Kong, trade and Chinese claims to large sections of the South China and East China Seas have increased fears in Seoul that it would become squeezed between its treaty ally and largest trading partner.

During his meeting with Park, Wang Yi said the countries should be “free from external interference” and shouldn’t interfere in each other’s domestic affairs, an apparent jab at Seoul’s tilt toward Washington.

Wang also called for the countries to work together to maintain stable industrial supply chains, a possible reference to fears that Chinese technology policy and U.S. security controls might split the world into separate markets with incompatible standards and products, slowing innovation and raising costs. South Korea is facing pressure from the Biden administration to participate in a U.S.-led semiconductor alliance involving Taiwan and Japan which China opposes.