The past few days have seen a spate of videos showing Ukrainians and their president defying an onslaught of Russian aggression. Who could fail to be moved by the video of a Ukrainian woman confronting an armed and jackbooted soldier, telling him to put sunflower seeds in his pockets so at least sunflowers will grow where he dies.

Or President Zelenskyy’s heroic selfies from Kyiv’s front line, which inspire far more widely than just among his countrymen?

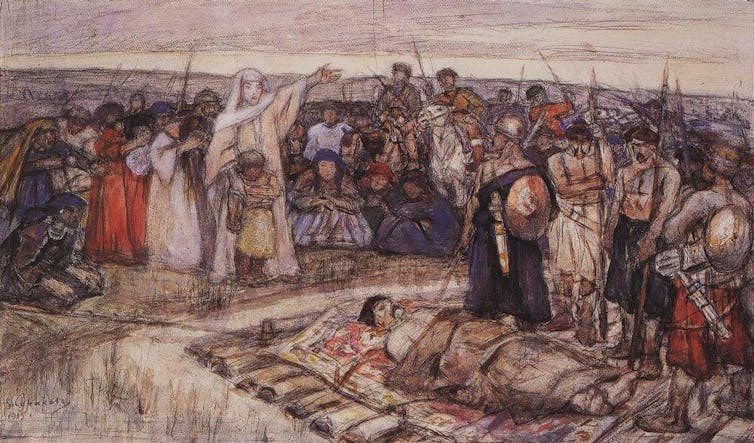

Ukrainians are used to adversity and they have a special medieval role model who personifies their bravery in the face of hardship. The Mongol horde destroyed her tomb in Kyiv in 1240 but a Ukrainian Orthodox cathedral dedicated to her was consecrated there as recently as 2010.

Olga of Kyiv, consort of Igor, second ruler of the Rurikid dynasty, is today recognised as one of Eastern Orthodoxy’s greatest saints. A fierce and proud woman who protected her young son and avenged her husband’s death, she was a crucial figure in the consolidation of the medieval kingdom of Kyivan Rus’ as a political entity and in its peoples’ conversion to Christianity.

Olga was born to Viking parents in Pskov, northern Russia, around the turn of the 10th century. She married Prince Igor young and may have been only 20 when the Drevlians, a neighbouring tribe, rose up against his rule and murdered him.

The Byzantine chronicler Leo the Deacon gives gruesome details of Igor’s killing: he was tied to two tree trunks which were then released so his body was split in two. Leo’s account may have been embellished (the ancient historian Diodorus of Sicily in fact tells a similar tale), but Igor’s death still left his wife and three-year-old son alone and potentially helpless in a particularly dangerous and brutal corner of the medieval world.

Burying her enemies

Olga’s legend was born of her actions in the weeks and months that followed. The Drevlians sent her emissaries to suggest she marry their leader Prince Mal. The Primary Chronicle, an 11th-century manuscript which is our main source for what follows, records Olga as greeting them deceptively, apparently to bide for time.

The account may be part-fictitious or at least exaggerated. Yet that is not the point: in medieval hagiography it is the morality of the tale that matters most.

“Your proposal is pleasing to me”, Olga told her interlocutors. “Indeed, my husband cannot rise again from the dead. But I desire to honour you tomorrow in the presence of my people. Return now to your boat, and remain there […] I shall send for you on the morrow […]

The hubristic Drevlian delegation took her at her word gleefully. But what they did not know was that she had arranged for a trench to be dug into which they and their boat were flung.

They were buried alive.

Olga summoned a second Drevlian embassy before the rest of the tribe had had time to learn of the first one’s fate. When they arrived she commanded her people to draw a bath for them.

The Drevlians then entered the bathhouse but Olga ordered the doors to be bolted and the building set ablaze.

For a third reprisal, Olga went to the place where the Drevlians had killed her husband, telling those present she wished to hold a funeral feast to commemorate him. Once the Drevlians were drunk and incapacitated she had her men massacre them.

Finally, she laid siege to the Drevlians’ base at Iskorosten (the modern-day Ukraine city of Korosten). She tricked those inside the city with an offer of peace: all they had to give up were three pigeons and three sparrows from each house.

But when Olga had the birds in her possession she had her men tie a sulphurous cloth to one of each one’s legs. The birds flew back to their nests for the night and the sulphur set every building on fire simultaneously.

Olga ordered her soldiers to catch everyone who fled the burning city so they could be extirpated or taken into slavery.

Her revenge for her husband’s death was at last complete.

Channelling St Olga’s spirit

Olga lived a further 25 years, residing in her son’s capital of Kyiv. She was instrumental in persuading him not to abandon the Ukrainian lands for "better prospects” further south on the Danube’s bank. Her grandson, Volodymyr the Great (c.958-1015), then expanded the kingdom into what is now seen as the first Russian principality (which Vladimir Putin now views as the forerunner of the imperial Russian state).

Volodymyr too is acknowledged as a saint for his role in completing the Christianisation Olga had started.

Olga’s Mad Max-style ventures ought to grate with us a bit today: the modern world really shouldn’t be a site of such bloodshed. That is why Russia’s sudden large-scale invasion into a peaceful country strike us as so shocking.

Yet Olga’s memory can clearly still provide an important focal point for Ukrainian resolve.

The Eastern Orthodox and Greek Catholic Churches recognise her with the venerable and extraordinary title “Isapóstolos”: Equal to the Apostles. She and Kyiv’s patron saint, St Michael the Archangel, remain key figures of intercession among those who need comfort in an hour of greatest need.

And Olga’s Christian faith, acquired during a visit to Byzantium late in life, can sustain others now just as it sustained her after her own tribulations.

Miles Pattenden has previously received research funding from the British Academy, the European Commission, and the Government of Spain.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.