For many Americans, taxes will most likely be one of their largest expenses in retirement. With some provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act coming to an end in 2025, there seems to be an additional emphasis on getting your IRA to Roth conversions done before “it’s too late.”

Even though IRA to Roth conversions may be more effective now than in future years, it begs the question, “How much?” Is it possible to convert too much? If so, how could that hurt your retirement? What risks would you take if you didn’t do any IRA to Roth conversions?

This article is intended to teach one of the main principles behind tax minimization. Please take into consideration that the following is an oversimplification of a complex situation. Many additional factors can play a role in your tax minimization strategies that will not be addressed.

How to decide when to convert

Let’s say you are 60, about to retire and have $1 million of pre-tax dollars saved in your IRA. Now, let’s pretend that the IRS has simplified income tax brackets and offered you two options:

Option 1: Convert as much as you want this year from your IRA (pre-tax) to your Roth IRA (tax-free) at a fixed rate of 20%.

Option 2: Lock in a guaranteed 15% tax with distribution limits for the rest of your life (you can’t do any large conversions).

Which would you pick?

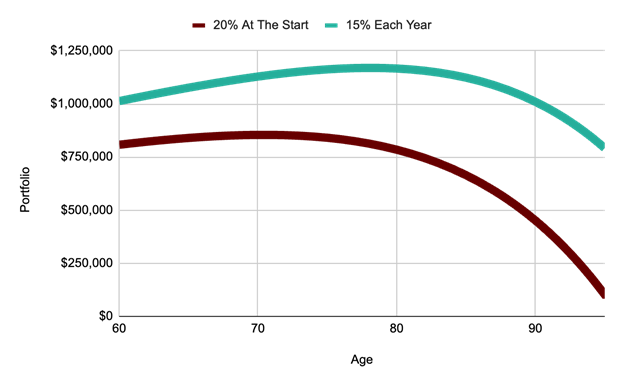

Assuming that you intend to spend $45,000, net of tax, per year, with a 2% cost-of-living adjustment, from a portfolio growing at 7% each year, and you live to 95, here’s what each scenario would look like.

Option 1: Convert everything

If you converted $1 million from an IRA (pre-tax) to a Roth IRA (tax-free) at an effective tax rate of 20% in year one, you would pay $200,000 and have $800,000 left over in your Roth IRA. That $800,000 can grow tax-free, distribute income tax-free and pass tax-free to your beneficiaries.

Option 2: Convert as you go

If you were to convert as you go, you would start with a pre-tax account balance of $1 million. However, your annual distributions would need to be higher in order to meet your net income goal of $45,000. In other words, to enjoy $45,000 after tax, you would need to take a gross distribution of $52,941. Assuming the promised 15% effective tax rate in this example, you would pay around $7,941 in taxes, leaving $45,000 net of taxes to spend in retirement. Don’t forget the net income target grows at 2% each year.

In this scenario, you would pay around $412,896 in taxes over the rest of your life (60 to 95 years old). Nothing would have been converted to Roth, meaning your beneficiaries would pay taxes on what is left.

Which scenario would you pick?

For some, you may want to convert everything up front and pay less in taxes. However, it may be considered deceptive to compare the two by the total tax dollar amount that was paid. Here’s why:

Assuming an annual portfolio increase of 7%, Option 1 would have about $102,309 left in the portfolio, tax-free, while Option 2 would have about $792,360 left in the portfolio, pre-tax. Even when you consider the fact that the beneficiaries will pay taxes, there’s still more to be enjoyed. Here is a chart that shows the projected account balances between the two options.

The conclusion

Tax minimization is a percentage problem, not a dollar problem. When people say, “I want to pay the least amount of taxes possible,” I can’t help but wonder if they understand this principle. Do you want to pay less taxes overall, or do you want to maximize your retirement income while preserving your estate? Those are two very different goals that require different strategies.

All things being equal, the math suggests that it may be better to convert a portion of your IRA assets into Roth assets until a certain point and then maintain a lower-than-anticipated tax bracket for the rest of your life.

It can be challenging to calculate and comprehend how much you should convert each year without a comprehensive financial plan. Tax planning/minimization is highly nuanced. Other factors that may affect your tax minimization strategies that can be flushed out with a comprehensive financial plan include (this isn’t a comprehensive list):

- Capital gains

- Social Security taxes

- Pension vs lump sum

- Required minimum distributions

- IRMAA (Medicare premiums)

- Longevity

- Charitable intent

- Where assets go when you pass

Once you convert a sufficient amount of assets, you may be able to maintain your taxable income within a certain bracket, follow this principle and potentially keep more of your hard-earned money. The difference could be several six or seven figures for you to enjoy as income or for your beneficiaries to enjoy when you pass.

If you want to tackle tax minimization on your own, I’d recommend using Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets so you can dive into the details and run several projections and analyses. If you want to work with a financial professional, vet the person carefully. As a rule of thumb, I recommend working with firms that can create financial plans and file your taxes. If they can file your taxes, there’s a good chance they have the depth of knowledge needed to tackle such a nuanced topic.