He twice voted in favor of convicting former President Donald Trump in impeachment trials. He excoriated his fellow senators who objected to certifying the results of the 2020 presidential election. He even scolded New York Rep. George Santos for his audacity in grabbing a prominent seat at the State of the Union speech after admitting to fabricating much of his biography.

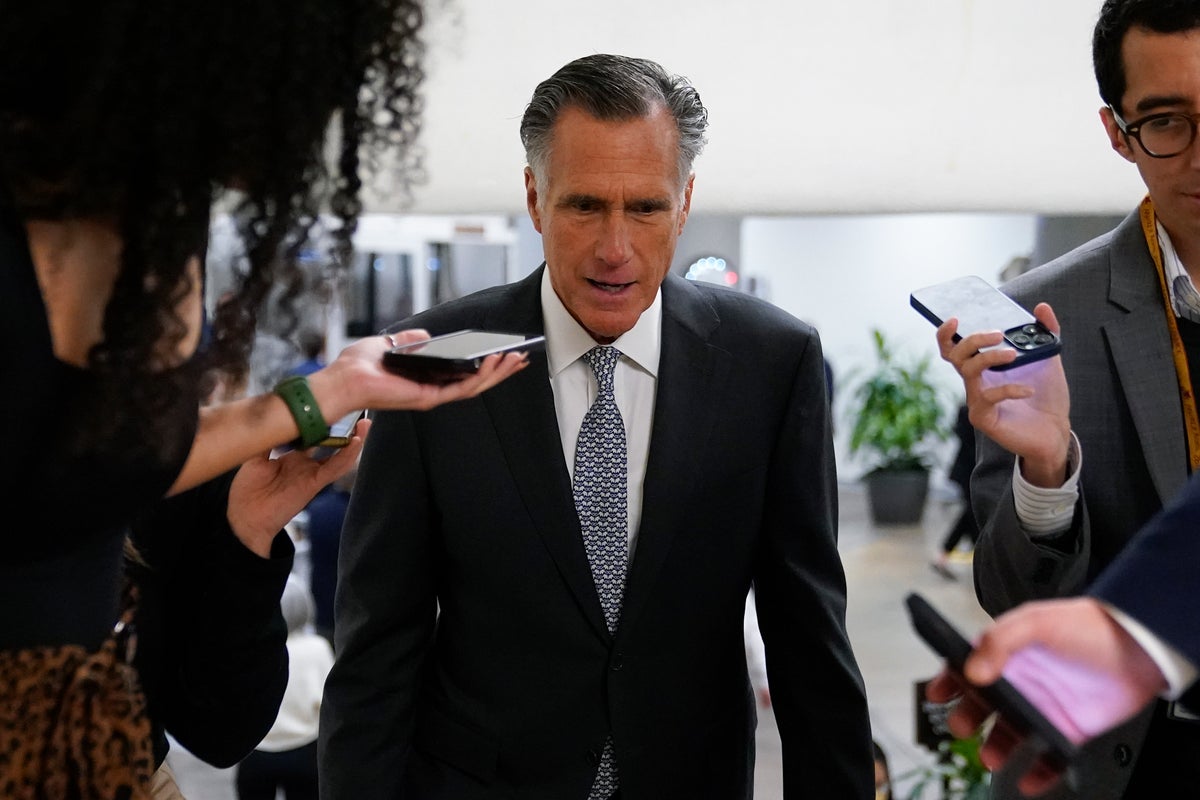

After four years in Washington, Republican Mitt Romney has established himself as a rare senator willing to publicly rebuke members of his own party.

But the Utah senator’s outspoken stances, along with his willingness to work with Democrats, have angered some Republicans in the deep-red state he represents and led them to cast about for someone to try to dethrone him a primary race next year.

The 75-year-old said he hasn’t made a decision on whether to run for reelection in 2024 and doesn’t expect to until the start of summer.

“I’m sort of keeping my mind open,” Romney said in an interview. “There’s no particular hurry. I’m doing what I would do if I’m running with staffing and resources, so it’s not like I have to make a formal announcement.”

His decision about whether to run again comes as Trump is making his third campaign for the White House, presenting Romney an opportunity to continue to serve as a chief foil to the former president.

But that could also sustain the backlash Romney has faced for serving as a check on Trump, including being heckled at the airport, narrowly avoiding censure by the state GOP and becoming an insult that other Republicans use to slam their rivals as suspect: “A Mitt Romney Republican.”

Romney has earned a reputation for bipartisanship, from his role helping broker a sweeping 2021 infrastructure law with Democrats to his being one of only three Republicans to vote to confirm President Joe Biden’s nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson as a Supreme Court justice. He helped negotiate legislation to protect same-sex marriages in December by demanding language ensuring that the rights of religious institutions would not be affected. And he joined 14 other Republican senators in supporting a sweeping gun control measure last summer in the wake of mass shootings.

“I didn’t come to the Senate to just fight and lose,” Romney said. “I came to actually fight and win. And I fell in with a group of Republicans and some Democrats who felt the same way and wanted to work together on issues of significance for the country and for our respective states.”

But what garnered Romney heavy booing two years ago and a near censure from the Utah GOP was his vote in 2020 that made him the first senator in U.S. history to vote to convict a president of his own party in an impeachment trial. Romney voted to convict Trump on House charges that he had abused his power by urging the president of Ukraine to investigate then-candidate Biden. He voted to acquit on a separate charge that Trump had obstructed the impeachment investigation.

Romney did it again in the weeks after the Jan. 6 Capitol attack, becoming one of seven Republicans to vote to convict Trump of incitement of insurrection.

Stan Lockhart, a former chair of the Utah Republican Party, said that while Romney’s votes in the impeachment trials drew a “huge negative outpouring,” he thinks that, nearly two years later, some of the support for Trump has softened and the hostility has “mellowed.”

Romney said he doesn’t have a measure of whether the backlash has eased, but said he was following an oath he took “to apply impartial justice.”

“People elect you and then you follow your conscience,” he said. “It would be sad if people who got elected to office tried to calculate their decisions based upon how popular it was at home. They have to do what they feel is absolutely right and then live with the consequences of that.”

No GOP challenger has stepped forward to run against Romney, but several prominent Utah Republicans are seen as potential candidates and at least on major conservative group is looking at spending in the race.

The anti-tax group Club For Growth, which used the phrase “Mitt Romney Republican” in attack ads in 2022, said the Utah Senate race is one where its political super PAC could likely get involved, throwing heft behind a conservative challenger.

“Even if he stays, I think there’s a desire among conservatives to have a real choice in Utah,” said Club For Growth President David McIntosh. “If somebody steps forward and is a credible candidate, we would definitely take a look at that.”

Former U.S. Rep. Jason Chaffetz, who gained the national spotlight leading the House Oversight committee through aggressive investigations of Hillary Clinton, said he is considering a campaign.

Utah Attorney General Sean Reyes, a Republican and staunch Trump ally, is among those seen as potential challenger. Reyes’ longtime political consultant Alan Crooks told the AP last year that Reyes was getting pressure to run and was well-positioned but wouldn’t say if he would launch a campaign.

The Western state allows candidates to secure a spot on the primary election ballot by collecting voter signatures — something a well-funded or popular candidate can generally do with ease — or by winning the support of 4,000 conservative leaning delegates at the state GOP party convention.

Romney is unlikely to win the support of delegates — he didn’t in 2018 — and the impeachment votes made it worse.

“Trump is still very popular among the base,” Utah GOP Chair Carson Jorgensen said. “Many Republicans felt it was a waste of time and taxpayer dollars to vote for impeachment.”