Prime drinks have been heavily promoted in Australia, leading to frenzied sales in supermarkets, as well bans in schools.

Prime offers two products: one is marketed as a “hydration” drink, the other as an “energy” drink. The latter comes with a warning it’s not suitable for people under 18 years of age, or pregnant or lactating women and isn’t legally sold in stores in Australia.

But both drinks may pose problems to under-18s and women who are pregnant or lactating.

What’s in Prime Energy?

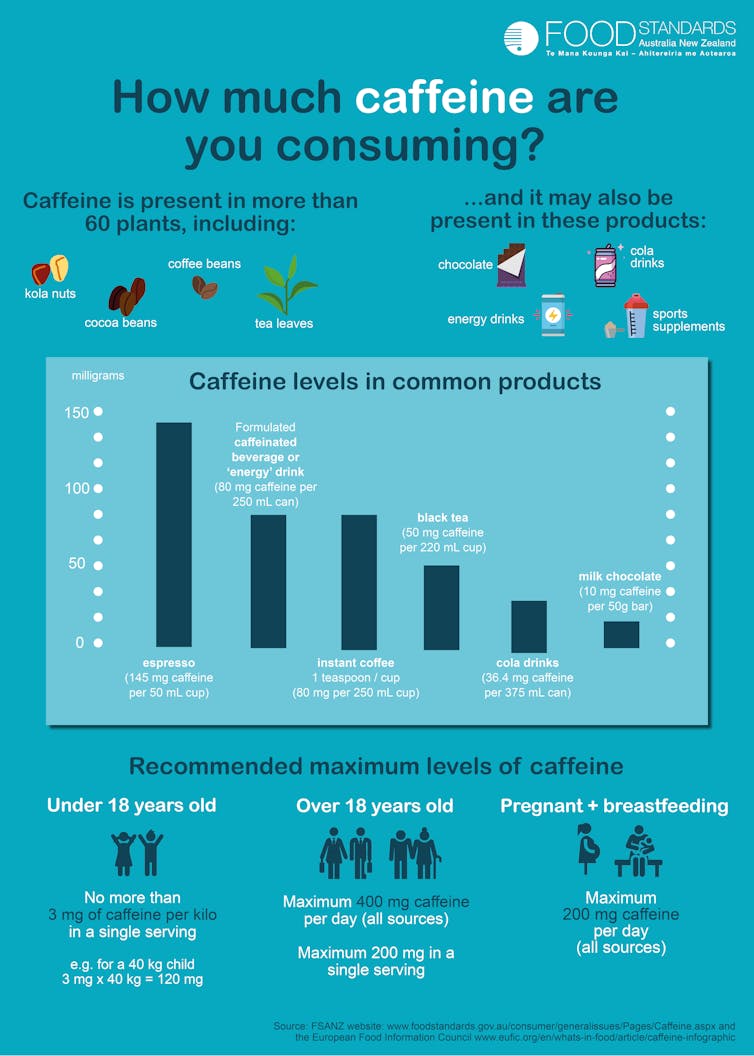

Prime Energy contains 200 milligrams of caffeine per can, which is equivalent to about two to three instant coffees. This caffeine content is roughly double what is legally allowed for products sold in Australia.

Despite its name, Prime Energy drink contains only about 40 kilojoules from carbohydrates, which is one of our body’s key sources of energy. The “energy” in Prime Energy refers to the caffeine, which makes you feel more alert and lessens the perceived effort involved in any work you do.

Caffeine does provide performance benefits for athletes aged over 18. However, given the high quantities in the drinks, there may be better ways to get caffeine in more appropriate doses.

Read more: Can coffee improve your workout? The science of caffeine and exercise

Caffeine is a concern during pregnancy

Health guidelines recommend limiting caffeine intake during pregnancy and while breastfeeding to below 200mg a day.

Theoretically, this drink alone, with 200mg of caffeine per can, should be fine. But practically, diets include many other sources of caffeine including coffee, tea, chocolate and cola drinks. Consumption of these alongside the energy drinks would increase the intake for pregnant women above this safety threshold.

Why is caffeine a problem for fetuses and babies?

Caffeine can cross the placenta into the growing fetus’s bloodstream. Fetuses can’t break down the caffeine, so it remains in their circulation.

As the pregnancy proceeds, the mother becomes slower at clearing caffeine from her metabolism. This potentially exposes the fetus to caffeine for longer.

Studies have shown a high intake of caffeine is associated with growth restriction, reduced birth weight, preterm birth and stillbirth. Some experts argue there is no safe limit of caffeine intake during pregnancy.

With breastfeeding, caffeine passes into the breast milk. It remains in the baby’s circulation, as they’re unable to metabolise it. Evidence shows that caffeine may make babies more colicky, irritable and less likely to sleep.

What about in kids?

Children also have a limited ability to break down caffeine. Combined with their lighter body mass, a caffeine-based drink will have a more pronounced effect.

As such, safe caffeine levels are determined on a weight basis: 3mg per kg of body weight per day. For example, children aged 9 to 13 years, who weigh no more than 40kg, should have no more than 120mg of caffeine per day. Those aged between 14 to 17 years who weigh less than 60kg should have no more than 180mg per day.

Studies have shown higher intakes increase the risk of heart problems, such as heart palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath and fainting. This may reflect underlying heart rhythm problems, which have in some case ended up with children and teenagers presenting to hospital emergency departments.

Read more: Should teens taking ADHD, anxiety and depression drugs consume energy drinks and coffee?

What about Prime Hydrate, which doesn’t contain caffeine?

This drink contains branch chain amino acids, or BCAA, which the supplements industry promotes as helping gain muscle bulk. There are three BCAA: valine, leucine and isoleucine.

However, there is no evidence they provide any benefit. As such, the Australian Institute of Sport has concluded they are not an effective supplement for athletes.

Supplements in general are not recommended in children or pregnant women as they have not been tested in these groups.

There is also concern about the impact of BCAA and how they may impact the growth of the fetus. A scientific animal study has shown altered patterns of growth with fetal mice.

No human studies have examined BCAA and fetal growth, so that research needs to be done before recommendations can be given to pregnant women. They should avoid these ingredients in the absence of evidence.

Similarly, there has been no testing of these supplements in children under 18 years, so there is no guarantee of their safety.

Performance-enhancing sport supplements are not recommended for children and adolescents, as they are still developing physically as well as refining and improving their sporting skills.

What does the science say about BCAA?

Scientists have been investigating how BCAA affect adults. Circulating BCAA can affect carbohydrate metabolism in the muscle and therefore can change insulin sensitivity. BCAA are elevated in adults with diet-induced obesity and are associated with increased future risk of type 2 diabetes, even when scientists account for other baseline risk factors.

Adults with obesity and insulin resistance have been found to have higher levels of BCAA. Emerging evidence suggests children and adolescents with obesity also have higher levels of BCAA, which may predict future insulin resistance, a risk factor for diabetes.

However we don’t yet know if these elevated levels of BCAA in the blood are because people are overweight or obese, or if it plays a role in them becoming overweight or obese.

Read more: Do athletes really need protein supplements?

The bottom line is we have clear evidence that caffeine is problematic for children and women who are pregnant and lactating. And there is emerging evidence BCAA may be also problematic.

Evangeline Mantzioris is affiliated with Alliance for Research in Nutrition, Exercise and Activity (ARENA) at the University of South Australia. Evangeline Mantzioris has received funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, and has been appointed to the National Health and Medical Research Council Dietary Guideline Expert Committee.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.