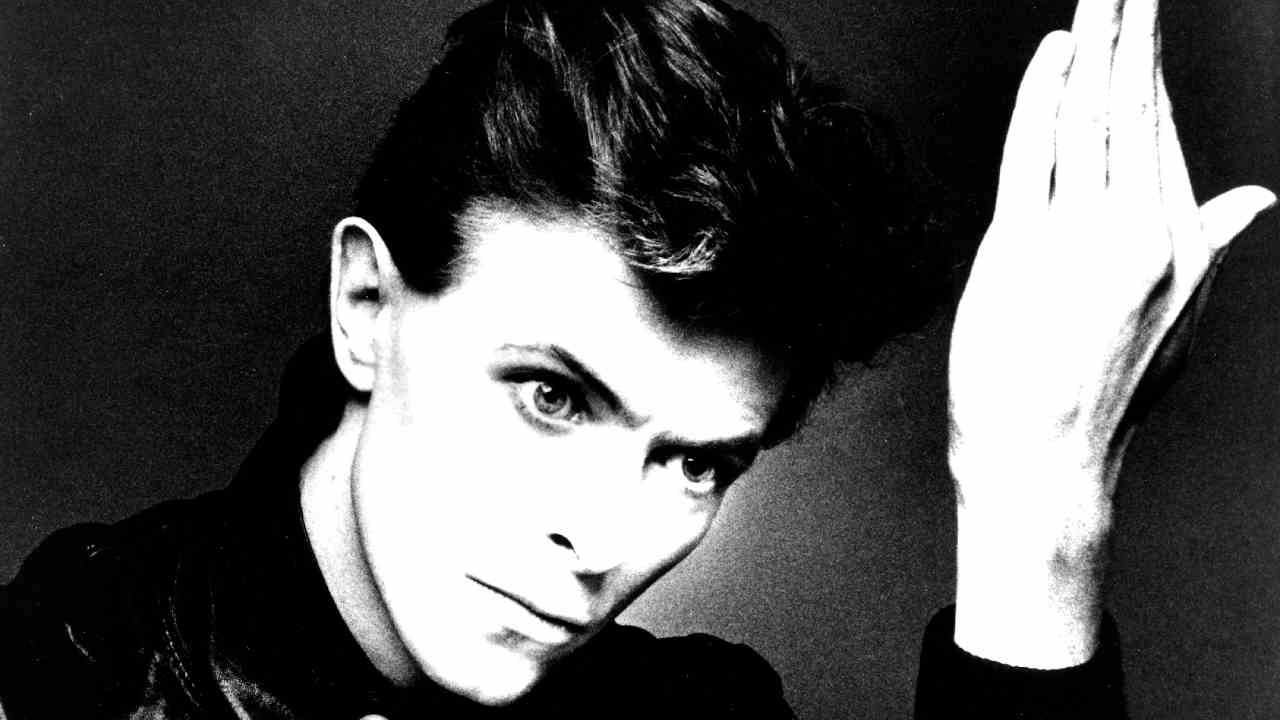

Life in Los Angeles was killing David Bowie. He’d moved to the city to begin work on Nicolas Roeg’s science fiction drama movie The Man Who Fell To Earth in July 1975, but a cocaine addiction he’d developed the previous summer had caused him to develop a series of damaging obsessions, not least with the occult.

Not sleeping for days, paranoid and delusional, he’d avidly read texts on religion, magic, the Third Reich, Nietzsche, Crowley and then habitually coke-babble half-considered concepts to a grateful press. He was teetering on the brink of losing everything.

Despite Bowie’s chemical-induced fall-out with reality, he retained a degree of self-awareness and a desire to get clean. To this end he made a decision to relocate to Europe. Having remade the acquaintance of ex-Stooge Iggy Pop he was determined to record with him, and where better than away from temptation at the Château d’Hérouville in France? After all, he was suddenly in need of a project upon which to focus his mind, as he’d just abandoned work on The Man Who Fell To Earth soundtrack. When informed he’d have to present his work alongside other composers just like any other candidate, he’d chosen to abandon the project, retaining Subterraneans for later use on Low, the first of three albums latterly corralled as The Berlin Trilogy. Upon Low’s eventual release, Bowie sent it to Roeg with the note: “This is what I wanted to do for the soundtrack. It would have been a wonderful score.”

As Bowie’s Isolar tour progressed from the US to Europe in the Spring of 1976, Iggy joined the entourage as Bowie’s constant companion and on arrival at Wembley, the singer bumped into Brian Eno. Turning on the charm, Bowie revealed he’d been avidly listening to Eno’s ambient album Discreet Music, released the previous year. “Naturally, flattery always endears you to someone,” Eno admitted, “I thought, God, he must be smart.”

Bowie had long been an admirer of Eno, especially Another Green World (1975) with its short pastoral instrumentals and inspired guitar interjections from King Crimson’s Robert Fripp. Bowie and Eno had an enormous amount in common, not least a shared fondness for krautrock, and vowed to keep in touch.

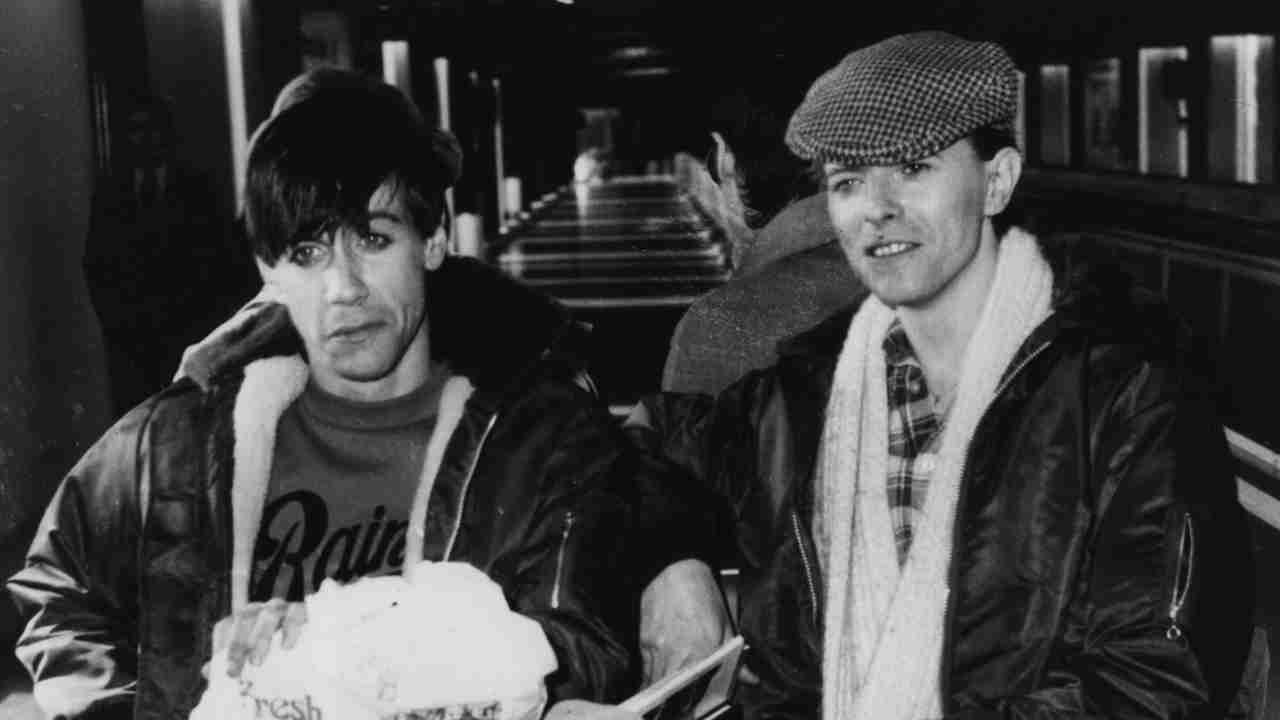

In June 1976, with the Isolar tour behind them, Bowie and Iggy arrived at the 18th century Château d’Hérouville on the outskirts of Paris (where Bowie had recorded Pin-Ups), and set to work on recording Iggy’s new album, The Idiot.

While the album would provide an experimental bridge between Bowie’s Station To Station and its follow-up Low, its recording was relatively haphazard, and the fruits of Bowie and Iggy’s Château-based labours more demo-level recordings than releasable product. The album would ultimately constructed in post-production at Berlin’s Hansa Tonstudio by Tony Visconti. Bowie’s long-time producer, who’d been absent from Station To Station due to scheduling difficulties, had returned to the fold after ringing Bowie and boasting of a device that “Fucks with the fabric of time”. It was this Eventide Harmonizer that would give Low its signature snare sound.

In its final incarnation, The Idiot proved to be something of a classic, though it wasn’t so much an Iggy album per se, as a dry run for a sound, or perhaps more accurately, a mood which Bowie latterly perfected in his Berlin Trilogy.

“Poor [Iggy] became a guinea pig for what I wanted to do with sound,” Bowie admitted, “I didn’t have the material at the time and I didn’t feel like writing at all. I felt much more like laying back and getting behind someone else’s work, so that album was opportune, creatively.”

Work on The Idiot concluded in August 1976, but Bowie was determined to get his own album recorded and released first, so it remained on ice until March 1977.

Low (working title New Music: Night And Day) was recorded between September and October 1976. Completed at Hansa, its groundwork took place at Château d’Hérouville.

Brian Eno arrived late for the sessions (after backing tracks for the album’s first side were almost done), so while he can’t be credibly credited as Low’s co-producer, his influence on the album’s second side is incalculable.

While the first side’s material seems fragmented, the work of a distracted mind, Low’s Eno-influenced flip, four near-ambient impressions of Bowie’s surroundings, comes across as more complete, rounded, stylistically assured.

Opening with a swift fade into a scene-setting vocal-free Speed Of Life, it’s immediately clear Low is no ordinary David Bowie album. He finally makes his presence felt on the intriguingly brief Breaking Glass, six-lines of cinematic jump-cuts offering insight into the actuality of Bowie’s coke madness: “Don’t look at the carpet/I drew something awful on it.” Bowie chalked out the Kabbalistic Tree Of Life at the peak of his occult obsession. “See!” he demands, revelling in his madness, before coldly concluding, “I’ll never touch you.”

Low continues with the lust-driven alienation of What In The World, before the album’s lead Sound And Vision single – an admission of the creative bankruptcy that hastened Low’s drastic change of tack. Visconti’s then wife Mary Hopkin’s ‘Doo-Doo-Doo’ backing vocals were the album’s only real concession to traditional pop and recorded as part of the musical backdrop rather than as counterpoint to the lyric. As with the rest of the album, lead vocals were written and recorded at the tail end of the production process.

There are only two more ‘songs’ on Low, and they’re hardly inspired: Always Crashing In The Same Car’s tarted-up anecdotage (Bowie had recently crashed his Mercedes in Switzerland) and Be My Wife’s short, sharp, normality-craving cry for help.

The central reason why Low and follow-up “Heroes” are largely instrumental is that Bowie was suffering with a writer’s block in the lyric department. He wasn’t writing songs like he used to, because he couldn’t. He could use Iggy as lyricist in the context of The Idiot and Lust For Life (and would again circa Tonight when suffering another bout of block), but when push came to shove, he had to find another way of working around his on-going inability to spew out lyrics in quite the same inspired way he had previously.

At root of Bowie’s problems was a short attention span: he’d done the rock poet bit, and was heartily sick of it, as he revealed in 1978: “(Eno) got me off narration which I was intolerably bored with. Narrating stories, or doing little vignettes of what at the time I thought was happening in America and putting it on my albums in a convoluted fashion. Singer-songwriter askew… And Brian really opened my eyes to the idea of processing, to the abstract of communication.”

Unbound from the constraints of poetry, where carefully contrived words could get in the way of pure emotional expression, Bowie was free to communicate solely via musical impressions (Warszawa’s coldly oppressive funeral doom), with human voices used only as lyric-free ornature (the evocative phonetic murmurings of Subterraneans).

He’d attempted to escape the demanding role of lyricist and partially automate the poetic process as far back as Diamond Dogs by adopting William Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s cut-up method. He’d sometimes even randomise composition, get musicians to improvise over a drumbeat, then pick those parts which worked best in tandem (irrespective of key) as a track’s basis. It’s a technique that positively reeks of Eno, whose boundary-breaking production concepts were often suggested by Burroughs-ian ‘Oblique Strategies’ cards. Printed with vague gnomic instructions (‘use an old idea’, ‘what would your best friend do?’), Eno’s cards were deployed to a far greater extent during the recording of “Heroes” and Lodger.

Upon delivery, Bowie’s record company RCA didn’t like Low anymore than they had liked (the still unreleased) The Idiot. Tony Visconti recounted an incident where, upon hearing Low, an RCA executive told Bowie: “If you make Young Americans II instead, we’ll buy you a mansion in Philadelphia”.

Somehow, Bowie’s former manager Tony DeFries, who still had a 16 per cent stake in Bowie’s output until 1982, heard a copy of the album and, because it ‘didn’t sound like a David Bowie record’ decided to protect his ‘investment’ by lobbying contacts at RCA to block its release. DeFries found sympathetic, like-minded ears at RCA, and Low’s original pre-Christmas release was delayed until January 14. It reached No.2 in the UK charts, while the single Sound And Vision hit No.3 – his biggest British hit since Sorrow four years earlier (the US was less receptive – the album and single peaked at No.11 and No.69 respectively).

RCA remained unconvinced of The Idiot’s commercial potential, and only grudgingly released it in the wake of the chart success of Bowie’s Sound And Vision. Iggy had returned to the road two weeks prior to its release with Bowie on keyboards, and while Bowie’s low-profile presence may not have distracted the audience’s attention from Iggy, his involvement certainly sold a lot of tickets.

Variously described as ‘dark’, ‘morbid’ and ‘disturbing’ at the time of its release, The Idiot, a touchstone for post-punk, goth and electronica, was on Ian Curtis’s turntable when the Joy Division vocalist committed suicide.

Following the Iggy tour, work commenced on Lust For Life in Berlin, but Bowie’s influence is nowhere near as obvious as on The Idiot. Retaining Hunt and Tony Sales on drums and bass respectively from the tour, Ricky Gardiner joined on guitar. Bowie co-wrote material, but left the arrangement to Iggy and musical director, Carlos Alomar, his mind clearly on “Heroes”.

While The Idiot had provided a handy sketchbook with which to try out rough drafts of the new Bowie sound, Iggy had served his purpose, and Bowie’s mind was mostly elsewhere. The American later admitted Bowie co-opted most of the basic structures for Lust For Life co-writes from existing rock standards – he was clearly saving his best for himself.

The album’s title track was, according to Iggy, written by Bowie, “in front of the TV on a ukulele… He cribbed the rhythm of this army forces network theme, which was a guy tapping out the beat on a morse code key.”

But the album itself, with the riff-driven The Passenger at its core, was significantly more Iggy than Bowie: loose-limbed, groove-based and steeped in Detroit-born brink-dwelling rock’n’roll.

Work on “Heroes” (described by Visconti as “a very positive version of Low”) commenced in July 1977. The existing Low band – Carlos Alomar (guitar), George Murray (bass), Dennis Davis (drums) and Eno – remained in place, but were augmented by King Crimson’s Robert Fripp, whose own band had split two years earlier and who laid down his distinctive and complementary lead guitar parts in just three days.

The vocal material on “Heroes”’ first side finds Bowie more confident in his new sound. He knows what it is, and having identified an optimum template, delivers the Berlin Trilogy’s defining moment in style. “Heroes”’ title track is an emotional epic, a towering triumph, the apogee of the Berlin period. Aside from Bowie’s gloriously histrionic vocal performance. It’s a basic two-chord trick save for the odd vocal crescendo but, when powered by Eno’s trio of oscillating VCS3 drones and three simultaneously soaring guitar arcs from Fripp, it’s simply irresistible.

Released in three languages (as “Héros” in France and “Helden” in Germany), this simple love song, inspired by Bowie watching a pair of lovers (latterly revealed to be Visconti and nightclub singer Antonia Maas) kissing in the shadow of the Berlin Wall is widely held to be David Bowie’s magnum opus, though, when released in the UK as a single in September 1977, three weeks prior to the album, it only managed to peak at No.24.

Every element of “Heroes” was recorded in Berlin’s Hansa Tonstudio. Bowie, Eno and Visconti were on a roll, but while it should be better than Low, it falls somehow short. The wall’s oppressive influence is just too strong. It’s bleak without being playful, there’s an all-pervasive gloom (the chilling Sense Of Doubt), a wallowing doom (the robotic, melodrama of Anthony Newley-channeling Sons Of The Silent Age, the only song Bowie brought to the studio at the start of recording) and an industrial chill (the wilfully teutonic V-2 Schneider).

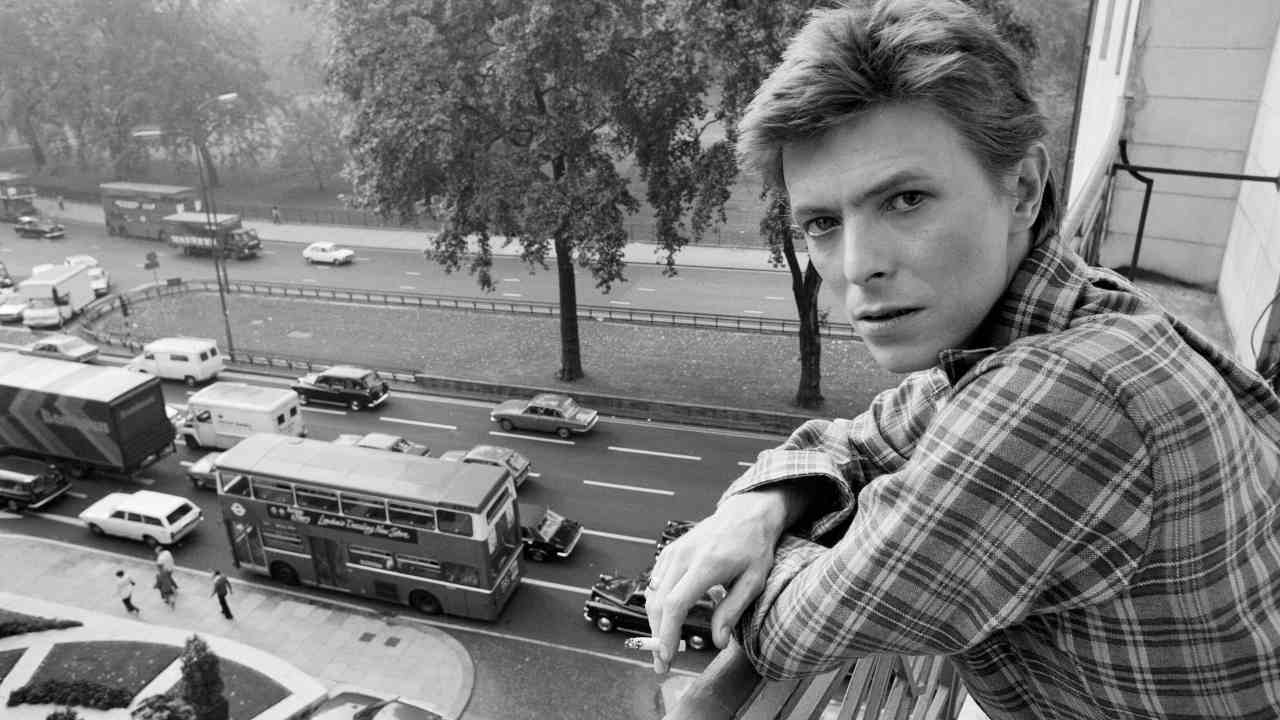

With Iggy absent, Bowie’s extra-curricular activities were not quite so tightly focused on getting hammered in nightclubs. He was going to art galleries with Visconti, stroking his chin over Oblique Strategies with Eno. His move to Berlin had been successful on both an artistic and personal level. He was living a reasonably normal life, had grown a moustache, excised the dye from his neatly cut hair and mooched about the place in checked shirt and jeans. He was able to be David Jones again, even pass for a native. But, aside from the joys of anonymity, the city’s essential edge offered an ample portion of grit for his creative oyster: “I like the friction… I can’t write in a peaceful atmosphere at all. I’ve nothing to bounce off. I need the terror.”

“Heroes”, released at the height of UK punk’s first wave, was marketed under the bullish slogan: ‘There’s old wave, there’s new wave, and there’s David Bowie…’

Touring throughout 1978, the Isolar II tour, commemorated in the double live Stage album, proliferated the new Berlin-era Bowie persona with an unbroken block of selections from the instrumental backsides of Low and “Heroes”, though cannily offsetting them with a collection of songs from The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

Eternally progressive he may have been, but he still knew how to please a crowd, and he wasn’t about to turn his back on commerciality anytime soon, as financially speaking, he was still suffering the effects of early 70s MainMan excess and mismanagement.

Despite the fact the Berlin spell was broken when Bowie set out on the nine-month Isolar II tour in March 1978, Lodger (working title: Planned Accidents) is still considered to be the third instalment of the Berlin Trilogy, when arguably The Idiot is a far better fit stylistically. While Lodger had a great deal in common with its two most recent predecessors – Eno randomising, Visconti producing, fashioned in Europe (Mountain Studios, Switzerland), Isolar II tour sideman/future King Crimson frontman Adrian Belew on hand to provide Fripp-alike stunt guitar – it’s a far more conventially-structured, if still doggedly experimental, Bowie album.

Rather than seeking to refine what had gone before, Lodger comes across as a feet-finding exercise in advance of the coming decade, a post-punk, position-reassessing mishmash of styles, and is only considered to be the third instalment in the Berlin Trilogy because Bowie said it was during its promotion. And he probably only said it because he had to say something. It was a handy handle for journalists to grab onto, and it certainly worked; we’ve been dutifully trotting out the same line ever since. Presenting Lodger as the final instalment of a Trilogy (or ‘Triptych’ as Bowie preferred to define it) served to legitimise its haphazard combination of styles, though rather than being Low Part III it’s possibly better, more accurately, described as Scary Monsters Part I.

While Eno’s influence on the album was outwardly minimal by comparison to Low and “Heroes” – there were no ponderous instrumentals on Lodger, let alone an entire second side of them – his Oblique Strategies often held sway in the studio. Hence Alomar, Davis and Murray swapping instruments to record Boys Keep Swinging (which shared its chord structure with Fantastic Voyage), reversing All The Young Dudes’ chords for Move On and revisiting The Idiot’s Sister Midnight with a new lyric (Red Money).

Eno’s Oblique Strategy cards were designed to ‘instruct random actions in order to bypass creative blocks’, but there’s very little suggestion of such stasis on Lodger (working title: Planned Accidents).

Elsewhere, D.J. deftly deals with the vacuity of celebrity, Look Back In Anger documents an encounter with the Angel Of Death, and Repetition tackles the horrific mundanity of routine domestic violence. An influential precursor of much of the appropriated world music to come in the 80s (Yassassin’s Turkish/Middle Eastern-reggae, African Night Flight’s deployment of pidgin Kiswahili), Lodger was a wide-ranging musical travelogue with Berlin only one of its many destinations. If there was a conceptual link between “Heroes” and Lodger, it’s The Secret Life Of Arabia, “Heroes”’ half-hearted, yet over-sold, shape-of-things-to-come afterthought.

Low’s influence reached the mainstream by the time of Lodger’s arrival two years later (a long time in 70s pop), its May 1979 release coincident with that of Tubeway Army’s Are ‘Friends’ Electric?, which rose to the UK No.1 in the following month.

Obviously, Bowie was no stranger to reinvention as he sought to reboot his coke-hobbled career in 1976, but why the Berlin Trilogy? Why the embrace of Brian Eno’s quasi-classical instrumental ambient tropes at this particular time and stage of his career?

Bowie was about to turn 30. No age now, but at the time a very big deal indeed. This was the age at which, as punk dawned, one became a ‘boring old fart’. He’d seen it happen to Jagger, and while no one had actually aimed that particular epithet at Bowie yet, it was surely only a matter of time.

It’s therefore possible that with Low’s, and “Heroes”’, post-Kosmische, Eno-ised instrumentals the steadily ageing pop idol was endeavouring to create more adult-targeted Bowie music. Music that would take him out of the generational rock market, where youth was still seen as the most important, if not essential, asset of any serious contender, and ultimately redefine him as the biggest star in his own particular musical firmament.

That said, Low’s first side was incredibly punk-friendly. Very 1977. Its songs were the antithesis of rock cliché and boasted an en vogue brevity, while Bowie himself sounded gloriously bored, even to the point of nihilistically “Breaking Glass in my room again”. How punk was that?

Brian Eno, meanwhile, presents a far simpler reason for Bowie’s drastic mid-career volte face: “He was trying to… duck the momentum of a successful career.”

But the juggernaut of stardom is not the easiest entity to bring to a halt.