The girl described as the “most credible” witness in the infamous Christchurch Civic Creche case speaks out for the first time

“Peter was a goldfish in a shark tank. I was also in the shark tank. There was no empathy. It was an attack on an innocent man. It was an attack on the truth.”

These are the words of the oldest and most “compelling and believable” complainant at the centre of the Christchurch Civic Creche case.

This week Newsroom published an investigation into the story of this girl through her parents, breaking their 30-year silence to talk about how they became embroiled in one of New Zealand’s longest-running and most controversial legal sagas.

That little girl is now a grown woman, a wife, and a mother herself. And for the first time she is also speaking publicly about what happened all those years ago.

“What happened to him was wrong,” she told Newsroom. “It wasn’t fair.”

Older than the other complainants and considered to be the most credible witness in the case against Peter Ellis, the childcare worker convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison for abusing children in his care, without her testimony the lead detective at the Christchurch Police Child Abuse Unit told her parents the case would fall over.

Home visits

That same detective had been drinking when he came to visit them at their house one day, sometime before Ellis’ conviction.

The parents told Newsroom that over the course of the visit they expressed doubts about the direction the court case was heading. He responded by telling them if they didn’t get their daughter to testify they would be as “perverted as Peter Ellis” and would be responsible for a “filthy bastard kiddie #@## going free”.

“He was so angry he stormed out and he slammed the door, essentially saying to both of us we were as guilty as Peter Ellis if we didn’t go through with this,” said the girl’s mother. “It was just bizarre. It was so bizarre.”

And he wasn’t the only one to show up at their home - the crown prosecutor also popped by.

“He had his lawyer wig on, the horsehair. But he was very charming. And when he had finished talking to us, we felt that it was the right thing again to go ahead with going to court.”

So they did.

‘Satanic panic’

Today, the daughter says: “I only have good memories of Peter Ellis and the Civic Creche. Peter never hurt me in any way or at any time.”

So how did things go so terribly wrong? To understand this, it helps to get a picture of the climate at that time.

Much of the lead-up to the creche saga can be found in A City Possessed, author Lynley Hood’s forensically detailed book about the case. In it, Hood delves into the sense of hysteria that began to grip the city.

It was the early 1990s and a bloodless, conservative Christchurch was all of a sudden ablaze with talk of satanic ritual abuse.

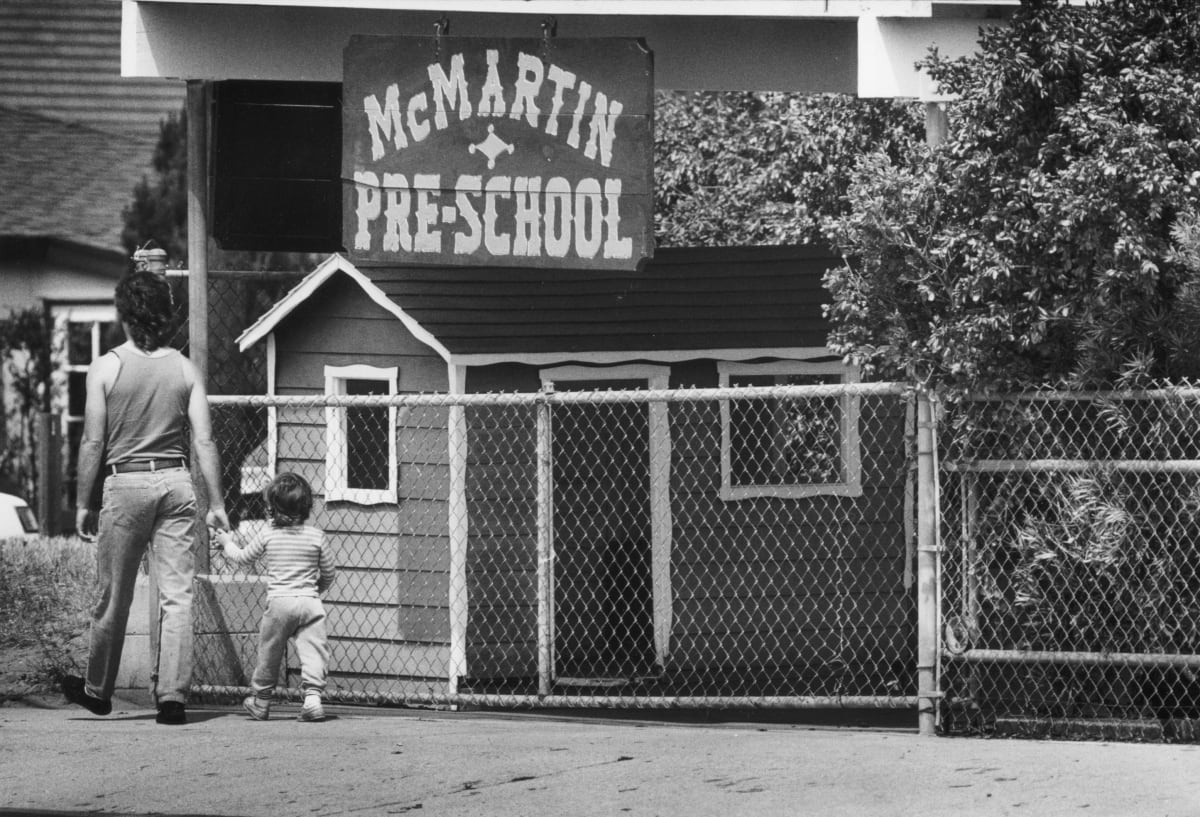

Panic that children were being sexually abused by childcare centre workers had been sweeping across parts of the globe, beginning in California in the early 1980s before spreading to daycares in Canada, Brazil and Europe.

Allegations emerged of secret tunnels, Satan worship, animal sacrifices and acts of violence that would leave no physical trace. In the United States, police swapped information and pamphlets on pagan symbols. Hundreds of childcare workers were arrested and dozens convicted.

In New Zealand, it arrived in the form of visiting “experts” from overseas.

American therapist Pamela Klein described the diagnosis and treatment of ritual abuse to a child sexual abuse conference in Wellington in 1990. (She was later found to have falsified her qualifications.)

The same year, an Upper Hutt police officer helped found the Ritual Action Network, an organisation dedicated to uncovering ritual child abuse, which held workshops at which attendees were told babies were being killed and eaten by a powerful network of evil men right here in New Zealand.

In 1991 they held their first major workshop as part of the week-long Family Violence Prevention Conference in Christchurch, during which it was reported there was clear evidence that devil worshippers were practising ritual sexual abuse against children.

Two months later, American paediatrician Dr Astrid Heger, who misdiagnosed mass child abuse in California in the early 1980s, visited Christchurch to lead a training session for physicians and sexual abuse specialists.

Later, the global phenomenon would be dubbed “the satanic panic”.

But it was into this environment that allegations of sexual abuse by workers at Christchurch’s Civic Creche began to emerge.

Rewards for answers

One of the key children to make such an allegation was a nine-year-old girl who had attended the creche.

Today, she thinks back on the police and child expert interview process - and why, after initially denying anything had happened, she then went along with it.

“At first it was a feeling of wanting to please the people by answering correctly. Gosh, kids love attention. I loved attention. There were rewards when I answered more questions. The more questions I answered ‘correctly’ the more my self esteem dropped.”

The girl’s mother says her daughter didn’t disclose anything right away, but by the fourth or fifth interview she began to talk about Ellis touching her.

“Our child was interviewed numerous times and there was often going over what had happened or leading questions. It was the time. And that would never happen today. If we look back on the way the children were interviewed, the way the police conducted themselves, I’d have to say that was not right.”

The daughter says as a girl she “started to feel super bad about myself”, but by then she was in too deep. “The lie was in place.”

On June 5, 1993, Ellis was found guilty on three counts of sexual violation, eight counts of indecent assault and five counts of performing, or inducing children to perform, indecent acts involving seven children.

Of those seven children, five of their parents worked in the sexual abuse field.

Some of the disclosures made by children from the creche included cakes and raisins being put up their bottoms, that Ellis killed people with axes, that he pushed children into a manhole with gorillas, smuggled them through dungeons, buried them in coffins, that children were made to kick each other in the genitals while adults stood around them in a circle playing guitars, and that Ellis’ mother had hung them in cages from the ceiling.

There was no physical evidence presented to court, despite some children undergoing invasive examinations. There were also no adult eyewitnesses. Ellis was found guilty based on the children’s evidential interviews and courtroom testimony.

The retraction

In 1994 the girl was with her mother when she heard a news story about Peter Ellis’ first Court of Appeal hearing starting the next day.

“I heard it on the radio when we were driving back from Nana’s, which was when I came clean and told my mother. It was a huge weight off my chest; although the weight has never ever lifted completely,” she told Newsroom.

What had started as a “wee story” as the daughter described it, had grown into a monster.

Her mother immediately contacted the Court of Appeal, and a senior barrister was sent around to interview the girl.

Despite finding she did not deviate from her insistence that she had lied in her original interviews and in court, and testing her statement “from a number of different angles”, the barrister did not believe her.

In the original court case, the Crown described her as “a compelling and believable witness” and her interviews as “clear and strong”.

But now, the barrister concluded she was “a very unhappy, confused young girl”.

Ellis’ counsel pushed back, stating, “Her courage in coming forward in all the circumstances is compelling. Her action cannot be lightly discounted. Of the original 118 children interviewed, just six now remained in support of the convictions … Surely the point has been reached where the fallout of complainants must be seen as alarming”.

But the Court of Appeal hearing would be another disappointment for Ellis. While the three charges against him relating to the girl were dropped, the remaining guilty convictions were upheld.

The girl’s mother says the impact of the “secrecy and shame” on her daughter’s life has been profound, and so has the guilt she feels as a parent. “We were intelligent people, and we were a caring, loving family. But somehow we got caught up in this.”

Yet the daughter told Newsroom she doesn’t blame her mother or father for what happened. “One hundred percent it wasn’t my parents' fault. They were victims of the system too.”

Convenient disbelief

In 2000, despite numerous calls for a Royal Commission of Inquiry and a pardon, the government announced there would be a much narrower Ministerial Inquiry, helmed by former chief justice Thomas Eichelbaum.

The family was hopeful someone would finally speak to them - to their daughter - about what had happened. But no one did.

In fact, in 28 years, no one from the Ministry of Justice has ever contacted them.

The mother says while there has always been an ongoing debate about the interviewing techniques used and the pressure the children were put under during court hearings and the inquiry, there is one person who could tell them exactly what it was like. However, her retraction is deeply inconvenient for the Crown so it has stuck with its mantra she is in denial.

“She certainly is not in denial, she never has been, she was not abused and no one knows that more than she does. It’s convenient disbelief.”

Now Ellis’ last chance, a posthumous Supreme Court judgment into whether his convictions will be upheld, is imminent.

The daughter told Newsroom she has only one wish: “I hope that he gets the justice he deserves, and this case can finally be put to rest.”