After a Newsroom investigation into the actions of Oranga Tamariki’s unjustified removal of four children, the state agency approved an ex gratia payment to the mother at the centre of the story – but is yet to let her know.

A year and a half feels like an eternity when you’re waiting for justice. That’s how long one mother had spent emailing and calling Oranga Tamariki in a vain attempt to secure some kind of financial compensation and support from the state child protection agency that uplifted her children “without basis” after she went to them seeking help.

Newsroom detailed the disastrous impact the uplifts had on the lives of the woman, who we called Eleanor, and her family in an in-depth investigation published late last year.

Emails from staff in Oranga Tamariki’s feedback and complaints department outline a string of unmet assurances that a payment was “being finalised” and “peer reviewed” following an internal investigation that found her children were unjustifiably uplifted.

In emails, one said the process would be completed late last year, another suggested early this year, and, most recently, a manager from the feedback and complaints department emailed the mother to say she “just wanted to reach out to say that we are hoping we are almost at a decision point” and gave an estimate of two weeks’ time.

This is despite an internal investigation finding in August 2020 - a full 19 months ago - that they had uplifted Eleanor’s children when they shouldn’t have.

Following further questions to Oranga Tamariki this week and just as we were due to publish this story, the agency emailed Newsroom late yesterday to say ex gratia payments for Eleanor had been approved.

In a statement to Newsroom, Glynis Sandland, deputy chief executive, services for children and families, wrote: “We can confirm that ex gratia payments have now been approved in acknowledgment of emotional distress and unnecessary legal costs caused by our social work failings in this case. We would like to apologise to ‘Eleanor’ and her whānau for any harm we have caused.”

This was news to both Eleanor and her lawyer, Jessica Matheson, who were surprised the information was coming to them via Newsroom.

Eleanor and Matheson are yet to be advised by OT about these payments. “I’ve had no formal notification, so therefore Eleanor’s position is reserved as to whether the offer is acceptable,” Matheson told Newsroom.

Matheson has been unimpressed with the continual delays and now the surreptitious timing of OT’s response, which she says comes following an unjustified delay which has further aggravated Eleanor’s trauma.

“It’s just completely unacceptable,” Matheson said. “They had already accepted there was a failure in their ‘quality of practice’, rendering the uplifts unjustified. In those circumstances where OT has already accepted they were wrong a year and a half ago it kind of beggars belief. What was the delay? And what about those people who don’t have a lawyer or the media battling for them?”

Matheson adds that OT’s shifting of the goalposts also caused existing trauma to be aggravated.

“The hole gets deeper and it makes it so much harder for mum and children to move on. OT has complete control as per usual. It feels like it’s a game that’s meant to, and I hate to say this, but irritate people who suffered from OT’s actions. It just feels like it’s some kind of subterfuge, that it’s a way of making litigants go away.”

Will the floodgates open?

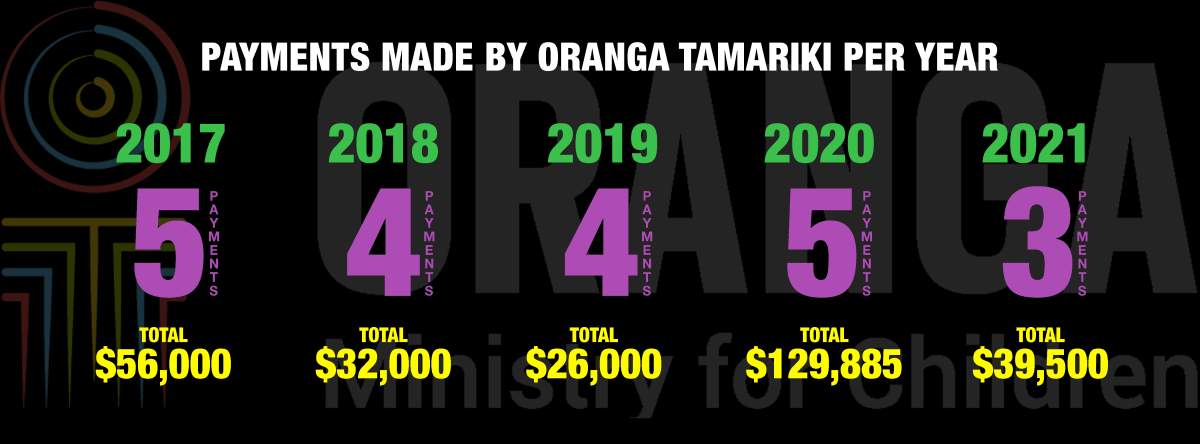

According to material released under the Official Information Act, since 2017 the average payout to those deemed to have suffered emotional harm or related costs as a result of OT failures around child uplifts, is just $13,000 - but almost all payments were less than that.

(Just 21 of these ex gratia payments have been made in that timeframe, and OT admitted it had only ever provided one ex gratia payment above $13,000.)

Given OT was, at its peak, uplifting an average of five babies a week from their mothers, as shown in all its stark reality in Newsroom’s watershed Hastings attempted uplift investigation in 2019, it is difficult to see how the extremely low numbers of ex gratia payments to date reflect the extent of harm OT caused.

An ex gratia payment literally means a payment made in good faith, but it does not recognise legal liability, rather a moral obligation when there has been a failing in their “quality of work”.

OT likes to point out it is actually the Family Court that determines whether children should be uplifted.

While this is technically true, it also dismisses the fundamental role affidavits submitted to the court by Oranga Tamariki staff and social workers have on Family Court judges’ decisions.

And judges rely heavily on the veracity and accuracy of OT’s own recommendations on whether to uplift a child or not.

The lawyer at the centre of the Hastings case, Janet Mason, has told Newsroom the young mother featured in Hastings story has never received an ex gratia payment from OT following their mistakes, and says she has a number of clients who have instructed her to take High Court proceedings seeking a declaration that the Oranga Tamariki uplifts of their babies were illegal, and will be seeking compensation.

This could potentially open the floodgates for further claims.

Five inquiries were launched following the Newsroom expose, including a 2020 report by the Chief Ombudsman based on a case study his office undertook. Comprising 74 cases of newborn uplifts, he found all were conducted “without notice”.

“It is clear from reading that report, and from what I have seen in the cases I have, that many of the s78 ex parte uplifts were illegal,” says Mason.

“Obviously, there will be many mothers (and fathers) in this situation, where they and their babies have been the victims of illegal uplifts. I don’t think this matter will be resolved by ex gratia payments from the Crown. It will have to go to court. Historically, New Zealand has paid a pittance to victims/survivors of state abuse. Certainly, the awards paid are nowhere near commensurate with the human suffering that has been inflicted on victims/survivors. There is nothing in recent history which gives me any reason to believe that the suffering of the poor, who have predominantly been the victims of state abuse, will now be properly valued and compensated for by the state.”

Matheson, who is taking on Eleanor’s case pro bono, agrees and thinks the ex gratia payments being paid out are far too low.

“If a judge has ordered an uplift following evidence provided by OT that is unsound, I propose that any right thinking New Zealander would view an amount such as $13,000 as completely disproportionate to the harm caused by an uplift.”

She doubts if most families even know ex gratia payments exist, and that if they did they would need to be well resourced to access them.

“Once you uplift children, you can never, ever remedy that trauma. And because the majority of people affected by OT failures are some of the most vulnerable families in our communities their ability to access quality advocacy is limited - plus the advocates themselves have to be willing to fight the good fight. Very few people actually have any energy and money to hire any type of advocate,” says Matheson.

OT’s ex gratia policy states that $75,000 is the maximum ex gratia payment able to be authorised, with ministerial approval.

Newsroom understands Eleanor, through her lawyer, proposed a package of support from Oranga Tamariki that included an ex gratia payment of more than $200,000, substantially more than has been paid to anyone else in relation to uplifts.

Whether Eleanor will accept the 11th hour offer put forward late yesterday - once she receives it - remains to be seen.

Mistake after mistake

In Oranga Tamariki’s own internal investigation into their treatment of Eleanor and her children, all but one complaint was upheld, showing mistake after mistake made by the agency.

In 2018, Eleanor had escaped an abusive relationship and was struggling to parent her high needs children alone without support. After hearing about Oranga Tamariki’s “respite care” service, something routinely provided for foster carers and advertised on their website as a service “for caregivers and tamariki to recharge”, she approached the agency seeking some childcare relief so she could have a break.

Instead, her children were removed and placed with family. After they were returned to their mother a few months later, a new social worker was assigned to their case and the children were uplifted again.

This time they were split up. The two older children were separated and placed with different non-kin foster carers, and the two youngest with their father, Eleanor’s abusive ex-partner.

What followed the second uplift was a spiral into hell, but Eleanor thought the internal investigation would mean some relief. Among other things, the report had found that her children had received physical injuries while in care, and that they had been uplifted “without basis”.

Finally, after heroic attempts by her, her family and friends, Eleanor’s children were returned in October last year.

To visit Eleanor at home today, it’s plain to see her daily struggles. She told Newsroom the constantly changing timeframe seems to be designed to wear victims down so they give up and go away.

“Even though they acknowledged they’ve messed up and that they had said that we met the threshold for compensation, now to actually get the compensation feels like it’s a whole other battle. It was a battle to get the kids back, and now it’s another battle to get what they’ve already said they’re going to give us. I have the sense that if I did nothing, that I would just never hear anything from them and they would think, ‘oh, that’s so wonderful, she’s kinda like curled up and died.’”

She says the past six months in particular have felt like Oranga Tamariki was playing a game to see how far it could stretch out the process.

“You just get sick of it. I just want this whole thing to be over.”

The long term harm caused to both Eleanor and her children has been exhausting, and while it won’t make up for the lost years and stress, she says financial support would enable them to heal as a family and move on with their lives.

“It’s like walking along the edge of the cliff and the more security you have the further and further away from edge of the cliff you can be. And that makes you feel safer so that your energy is able to be directed into your children rather than that stress and having that feeling like ‘oh god the power bills coming, 'cause it eats your energy away.”

“I want to use the money to make our lives as comfortable for my children as I can. I want to take away as much stress as I can so we can focus on healing together and knitting our family back together.”

She says while some people may think getting her kids back is enough of a happy ending, some of the harm has been irreparable, and no amount of money can bring back what was taken.

“How do you put a price on the years of your children’s lives that you’ve lost?”