Optical illusions play on the brain's biases, tricking it into perceiving images differently than how they really are. And now, in mice, scientists have harnessed an optical illusion to reveal hidden insights into how the brain processes visual information.

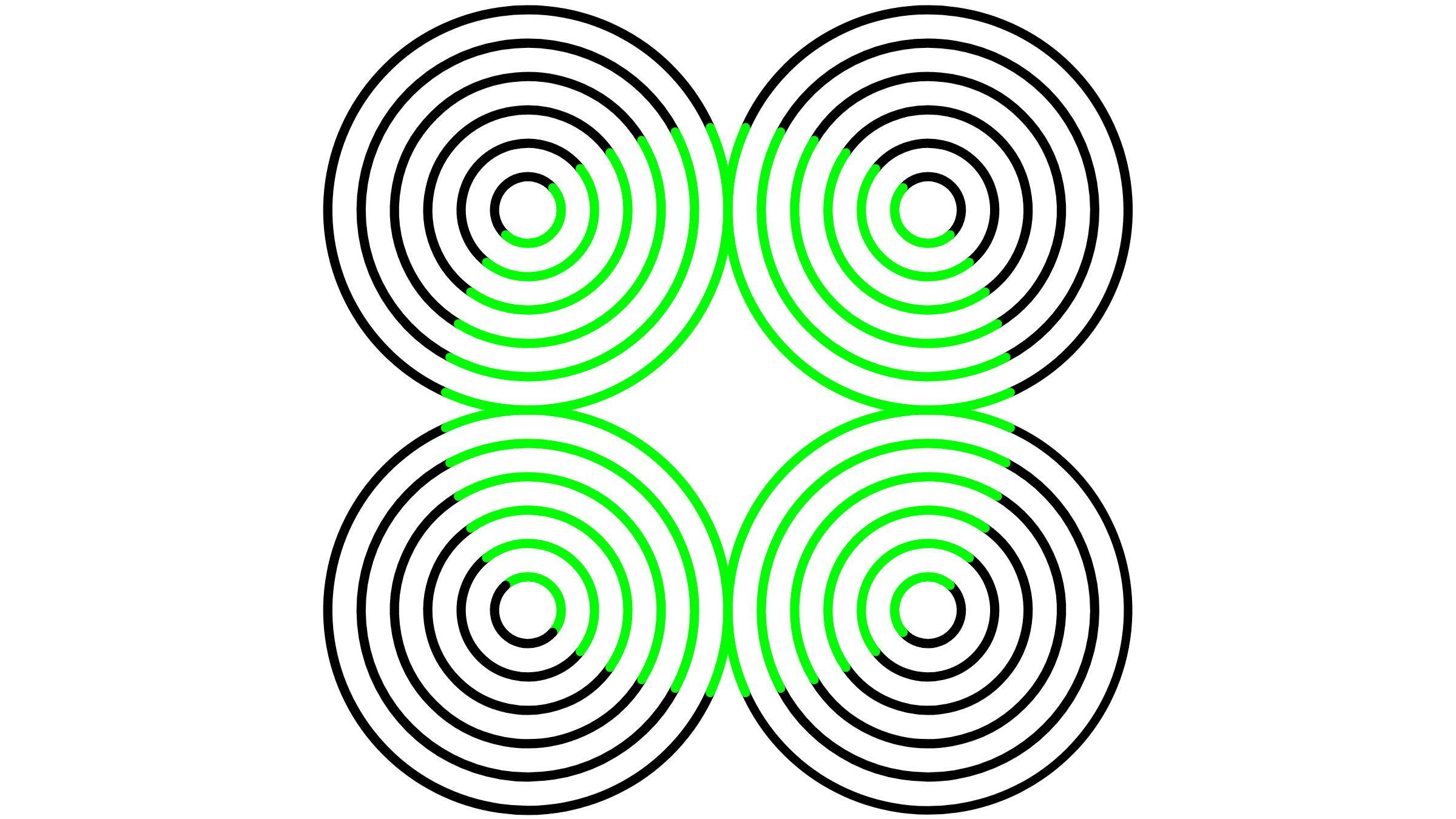

The research focused on the neon-color-spreading illusion, which incorporates patterns of thin lines on a solid background. Parts of these lines are a different color — such as lime green, in the example above — and the brain perceives these lines as part of a solid shape with a distinct border — a circle, in this case. The closed shape also appears brighter than the lines surrounding it.

It's well established that this illusion causes the human brain to falsely fill in and perceive a nonexistent outline and brightness — but there's been ongoing debate about what's going on in the brain when it happens. Now, for the first time, scientists have demonstrated that the illusion works on mice, and this allowed them to peer into the rodents' brains to see what's going on.

Specifically, they zoomed in on part of the brain called the visual cortex. When light hits our eyes, electrical signals are sent via nerves to the visual cortex. This region processes that visual data and sends it on to other areas of the brain, allowing us to perceive the world around us.

Related: The brain-bending secret behind hundreds of optical illusions has finally been revealed

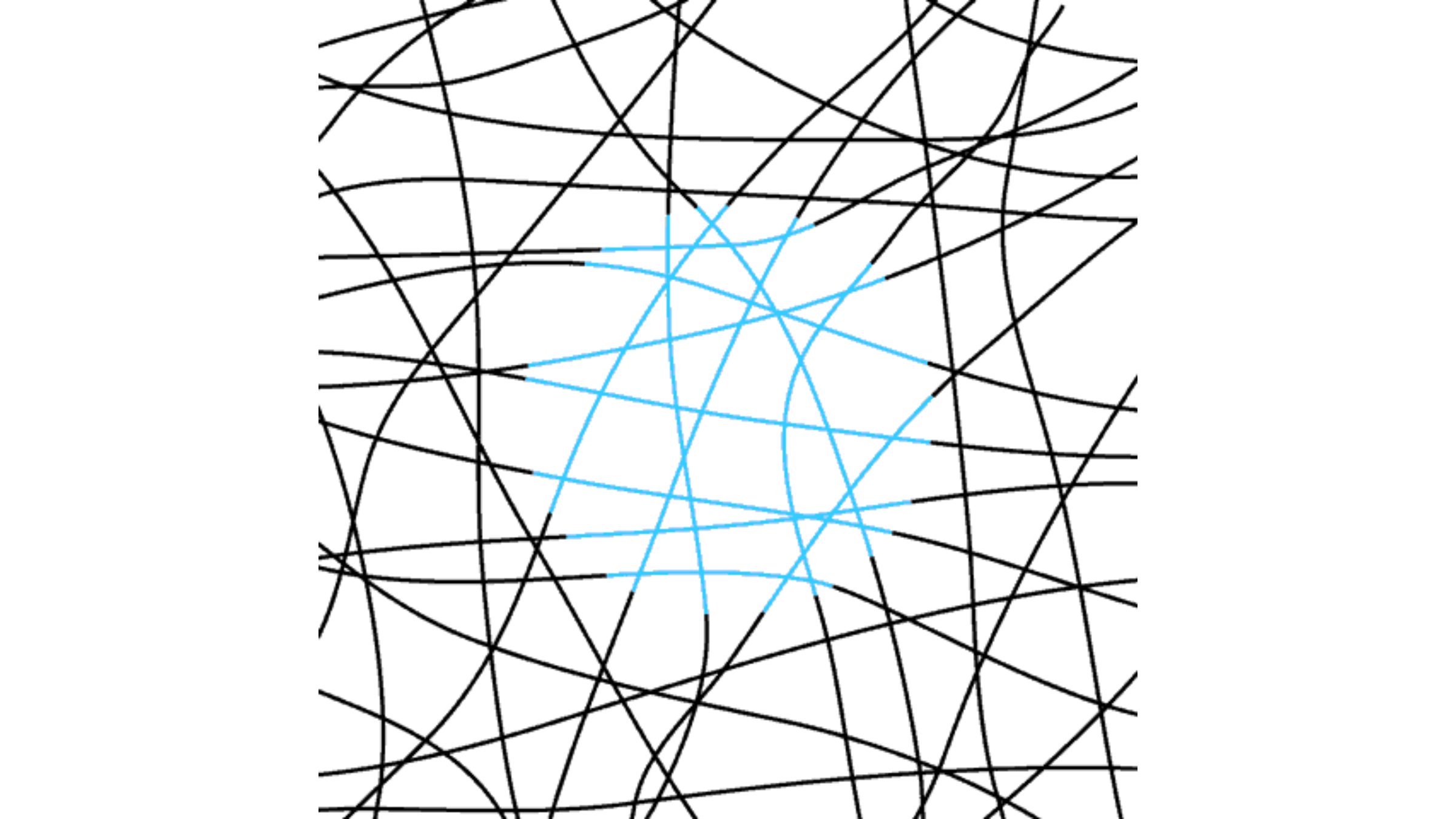

The visual cortex is made of six layers of neurons that are progressively numbered V1, V2, V3 and so on. Each layer is responsible for processing different features of images that hit the eyes, with V1 neurons handling the first and most basic layer of data, while the other layers belong to the "higher visual areas." These neurons are responsible for more complex visual processing than V1 neurons.

Until now, scientists have debated the extent to which V1 neurons respond to illusory brightness, such as the brightness people perceive when looking at the neon-color-spreading illusion. In a series of lab experiments in mice, researchers have now shown that these neurons play a fundamental role in this process and that their activity is also tempered by feedback from V2 neurons. So there's a volley back and forth between these different layers of the visual cortex.

This knowledge may bolster our understanding of consciousness, the researchers said in a paper published April 23 in the journal Nature Communications.

"The observed relationship between V1 and V2 in processing the illusion implies that consciousness is a top-down process," as opposed to a bottom-up process, co-author Masataka Watanabe, an associate professor in the department of systems innovation at the University of Tokyo, told Live Science in an email.

Top-down processing refers to the way our brains interpret our surroundings by taking prior experiences into account, rather than solely relying on visual stimuli alone. By contrast, pure bottom-up processing would take the different features of an image and snap them together like puzzle pieces, making a coherent picture without input from a person's memory.

Other studies have implied that consciousness is a top-down-process, but this mouse study provides direct evidence for it, Watanabe said. The answer isn't black and white though, as some argue that consciousness likely arises from a mixture of both.

What is the new evidence? In the study, mice were shown a combination of neon-color-spreading illusions and other, similar-looking patterns that did not trigger the illusion. Simultaneously, Watanabe and colleagues measured the activity of neurons in the rodents' brains with implanted electrodes.

The team also measured whether the mice saw the illusions as bright by assessing how much the pupils in their eyes dilated or constricted. This response matched that seen in humans when we perceive changes in light levels.

V1 neurons respond to both illusory and non-illusory images, but they take longer to respond to the former. This supports the theory that V1 neurons need feedback from higher visual areas to process these types of illusions, the team reported.

The researchers then tried experimentally inhibiting the activity of the higher visual area neurons, finding that V1 neurons were less likely to respond to the illusions. This provided further evidence that a higher-level feedback loop is needed to perceive the illusion.

Going forward, the team plans to conduct further studies in which they'll mess with the activity of higher visual area neurons in mice, Watanabe said. They hope that this will shed more light on the neural mechanisms underlying consciousness in mice, and by extension, in humans.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!