Between 1976 and 1978, an extrajudicial campaign of violent repression was waged by South American dictatorships against political dissidents and exiles who spoke out against domestic repression and military rule.

Operation Condor, as this campaign was known, has since inspired multiple novels, plays and exhibitions, not to mention a forthcoming HBO series. The latter, based on The Ashes of the Condor, the 2014 novel by Uruguayan writer Fernando Butazzoni, tells the story of a young man whose parents fled Uruguay during the military dictatorship.

In 1992, a cache of about 700,000 documents were discovered in a police station in Asunción, Paraguay. Dubbed the Archives of Terror, these papers comprehensively recorded the activities of the Paraguayan secret police since the 1970s.

These papers comprehensively recorded the activities of the Paraguayan secret police throughout the dictatorship of General Alfredo Stroessner (1954-1989). Ever since, scholars and journalists, in Chile, Argentina and the US have investigated this transnational terror network.

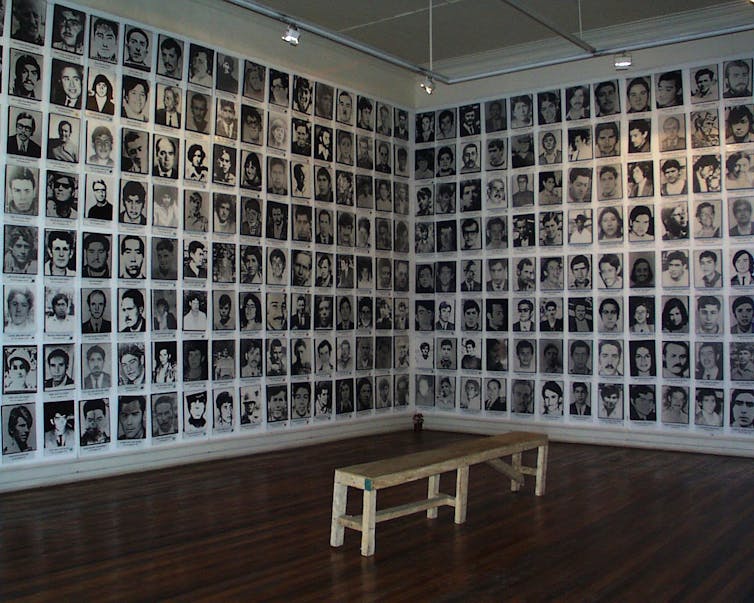

Between 2017 and 2020, I compiled the first database on human rights violations in South America. I recorded at least 805 victims of abductions, torture, sexual violence, baby theft as well as extrajudicial executions and disappearances, taking place between 1969 and 1981.

How Operation Condor came about

As I explain in my new book, The Condor Trials, a new case which has been brought against Italo-Uruguayan navy officer Jorge N Troccoli, constitutes the 48th criminal investigation into these years of terror, since the 1970s. The first hearing was held in Rome on July 14, 2022. Troccoli stands accused of the 1970s murders of two Italo-Argentinians and one Uruguayan national.

My research has shown that the majority of Condor victims (48%) were Uruguayan nationals. Argentina was the key theatre of operations with 69% of all victims being targeted there. Furthermore, the primary targets were political activists (40%), followed by members of guerrilla groups (36%).

Research normally places Condor’s beginnings in 1974-1975. My research, however, has shown that from as early as 1969, Brazilian refugees in Uruguay, Argentina and Chile were targeted and, in many cases, killed.

Within the geopolitical context of the cold war, the national security doctrine was formulated in the United States, founded on the idea that achieving national security trumped all other governmental concerns. Military leaderships in South America took inspiration from this doctrine to wrest control of their own civil governments.

The 1954 coup d'état in Paraguay, which saw President Federico Chávez’s government overthrown by the army, was the first. Putsches followed in Brazil (1964), Bolivia (1971), Uruguay, Chile (1973) and Argentina (1976).

The military dictatorships thus installed brutally repressed all forms of political opposition. Thousands of illegal arrests were made. Torture and sexual violence was prevalent. Disappearances, baby thefts and extrajudicial executions were committed. The violence saw citizens throughout South America flee their home countries.

Brazilians sought safe haven in Uruguay and Chile from 1968, when domestic repression in Brazil intensified. They were the first to be targeted.

By early 1974, thousands of Brazilians, Bolivians, Chileans, Paraguayans, and Uruguayans were living in Argentina. Active in denouncing the crimes against humanity being committed across the region, they came under increasing fire from their respective dictatorships.

On November 25, 1975, representatives of the security forces of Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay were invited by the head of Chile’s secret police to a working meeting of national intelligence in Santiago, Chile. Operation Condor was born.

The Condor system was composed of four elements. First, the secret Condortel communications system allowed members to share intelligence. Second, Condoreje, a forward command office, located in Buenos Aires, oversaw operations on the ground in Argentina in particular. Third, a databank in Santiago, Chile, centralised shared intelligence information. And four, the secret Teseo unit was tasked with carrying out attacks against leftist targets in Europe.

How women have fought for justice

A group of justice seekers – survivors, victims’ relatives, activists, legal professionals and journalists – have long been dedicated to bringing these human rights violations to light. Many of these campaigners are women: the mothers, grandmothers, wives, sisters and daughters whose lives have been directly impacted by Condor. As Argentinian prosecutors told me, these justice seekers “absolutely galvanised all investigations that occurred: without them, nothing would have happened”.

American journalist Jack Anderson first used the term “Condor” in August 1979, in an article in the Washington Post. However, as early as 1976, Uruguayan journalist Enrique Rodriguez Larreta and former trade union activist Washington Perez testified to Amnesty International and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights about the ordeals suffered in Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

The Argentine general election of 1983 hailed the gradual return of democracy and constitutional rule to South America. Brazil and Uruguay followed suit in 1985, then Paraguay in 1989, and Chile in 1990.

In countries including Chile and Brazil, the outgoing regime sought to guarantee its own impunity with new amnesty laws. In others, including Argentina and Uruguay, newly democratic parliaments aimed to prevent the return of military rule with similar laws. As a result, all criminal investigations into past atrocities were shelved.

Despite these setbacks, since the late 1970s, multiple criminal investigations into Condor atrocities have gone ahead. Thirty of these cases have gone to sentencing, four trials are currently ongoing, three have been shelved and 11 are in pre-trial.

To date, 112 South American military and civilian officials, including former dictators and government ministers, have been brought to justice. This most likely only represents a fraction of those guilty. While there is no official estimate of the total number of perpetrators, it is likely to be in the thousands.

This process is important for the victims, their families and the wider societies that suffered in the past. It is also crucial in preventing such atrocities from being perpetrated in the future.

Moreover, transnational repression of exiles and dissidents remains a pressing issue the world over. According to the US thinktank Freedom House, 85 such incidents occurred in 2021 alone. Justice for Operation Condor stands, therefore, as a clarion warning to authoritarian states today.

Francesca Lessa’s project on Operation Condor received funding from the University of Oxford John Fell Fund, The British Academy/Leverhulme Trust, the University of Oxford ESRC Impact Acceleration Account, the European Commission under Horizon 2020, and the Open Society Foundations. She has advised lawyers, activists, and prosecutors involved in the Condor Trial in Italy. She is the Honorary President of the Observatorio Luz Ibarburu, a network of human rights NGOs in Uruguay.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.