Crystals packed inside Apollo's lunar rocks suggest that the Moon could be a much older age than we thought.

Half a century after the last Apollo mission departed the Moon in December 1972, scientists have taken a fresh look at its precious parcels. A team sharpened the lunar rocks the astronauts had ferried to Earth, and then, by using a precise dating technique that measures the decay of unstable molecules called isotopes, researchers concluded that the Moon is at least 4.46 billion years old. Their new estimate, published in a new study in the journal Geochemical Perspectives Letters, suggests the Moon is older than previously estimated by 40 million years.

“It’s amazing being able to have proof that the rock you’re holding is the oldest bit of the Moon we’ve found so far,” Jennika Greer, lead author of the new study and former doctoral candidate at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, said in an announcement.

How did the Moon form?

The crystals that researchers examined are traces of a violent encounter between ancient Earth and a Mars-sized object. Fittingly, it's called the Giant Impact hypothesis.

This crash is time zero on the clock for the Moon’s existence as we know it. The event would have caused a molten ocean across the Moon’s entire surface.

As Philipp Heck, curator for meteoritics and polar studies at the Field Museum and the study’s senior author, explained in the announcement, “When the surface was molten like that, zircon crystals couldn’t form and survive.” Once the magma ocean cooled down, the zircon crystals would begin to form. They are, therefore, a good way to estimate the minimum possible age for the Moon.

How did they figure out the Moon’s age?

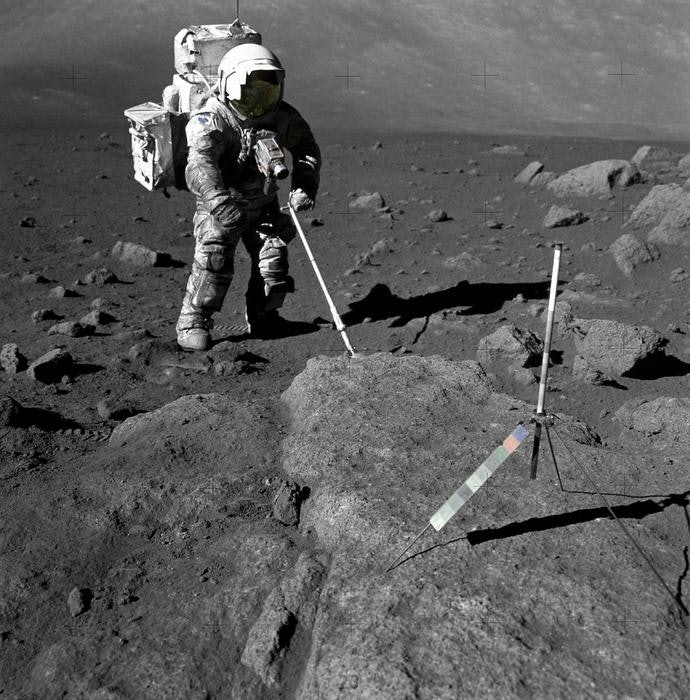

Greer says the team used a focused ion beam microscope like “a very fancy pencil sharpener” to prepare the lunar sample for observation. The team produced five of these “nanotips.” Ultraviolet lasers then evaporated atoms from the tip; this allowed the team to learn what they were made of.

The next step was to look at the proportion of different isotopes. The team could then discern how many atoms had transformed during the passage of time as they underwent radioactive decay. This technique, which Heck described as an “hourglass,” provides a reliable way to learn the ancient age of a sample.

This new study is proof that astronomers need only peer into the nearby universe to make exceptional discoveries.