High-profile legal action against the Climate Change Commission may be decided on the technical details, but it raises moral issues not so easily settled, Marc Daalder writes

Analysis: A coalition of lawyers urging greater action on climate change have told the High Court the Climate Change Commission made a mathematical error in its advice to the Government on domestic and international emissions cuts, meaning its proposed budgets and targets aren't consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees.

The case, which started last Monday and ran through Friday (with an interruption on Wednesday as police cleared nearby Parliament grounds), focused on a range of technical carbon accounting issues. Newsroom has previously reported on some of the arguments in the case and Stuff's Olivia Wannan has covered each day of the hearing.

One of the key disagreements is centred on the commission's attempt to say its recommended emissions budgets and advice on New Zealand's new Paris target are consistent with the emissions reduction pathways from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) landmark 2018 report on 1.5 degrees.

While carbon dioxide under the commission's recommendations is set to fall by 2030, it only falls as steeply as the IPCC pathways if the starting point is artificially inflated by excluding the carbon sucking impact of New Zealand's forestry (while including that benefit in the end goal).

The commission had a range of responses to this criticism from Lawyers for Climate Action. First, it said that its maths checks out – even though two lead authors of the pathways chapter of the 2018 IPCC report said the commission was comparing apples with oranges.

Second, it said the IPCC pathways show the necessary trajectory for global emissions. New Zealand's national circumstances are different from the global average so we don't need to track the IPCC pathways identically in order to be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5 degrees. On a similar note, the commission said it could choose not to reference the IPCC report at all, as the document wasn't the sole arbiter of what it means to be 1.5 consistent.

These latter two arguments bring up the ethical issue at the heart of the judicial review case. Ultimately, the court case will be decided on legal and technical issues. The bar for deciding against the commission is high – the climate lawyers must show that no reasonable person in the position of the commission would have given the advice it did.

But the moral substance of the dispute between the climate lawyers and the commission is not something that's easily settled: What does it mean to be consistent with 1.5 degrees, in a world where most countries have less historical responsibility for current warming than New Zealand and even less means to reduce their own emissions?

The commission's view is that any emissions budgets that form a credible pathway to net zero long-lived gas emissions in 2050 is by definition consistent with 1.5 degrees.

"The targets in the Act were set at a level that the Government viewed to be in line with the effort of limiting warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels," the commission wrote in its final advice last year. "At a high level, this means that any emissions budgets set to meet our domestic targets are also consistent with what Aotearoa needs to do to meet international obligations."

The IPCC's pathways "provide useful insights for considering how our recommended emissions budgets contribute to limiting warming to 1.5°C" but "represent global averages and do not set out prescriptive pathways for individual nations".

Pretty much everyone agrees that the IPCC's global pathways shouldn't set exact expectations for each country. But where the commission and the lawyers differ is over how New Zealand's own circumstances should be accounted for.

The commission refrained from advising on how the Government should think this through when setting its Paris target, which will incorporate domestic emissions cuts and ones that happen overseas but which New Zealand pays for. On those domestic cuts, however, it sketched a path that was by the lawyers' accounts much less ambitious than what's needed from the global community on average.

Joeri Rogelj, who was the coordinating lead author for the 2018 report's chapter on global pathways, said in an affidavit that New Zealand should be doing more than the global average, not less.

"My more fundamental reflection is that from an international climate equity perspective it is conceptually questionable to apply reductions from global emissions pathways directly to the national context of an individual country. Scholarly literature uses principles of international environmental law (such as a country's responsibility for historical contributions to climate change or capability to act to mitigate it) to discuss and estimate fair shares of individual countries to a global effort of keeping global below specified levels," he said.

"For example, a recent peer-reviewed study estimates that New Zealand's internationally fair contribution to a global pathway that would keep maximum global warming below 1.7°C implies at least a 67 percent reduction in net-net emissions reductions by 2030 relative to 2010."

Under the commission's proposed budgets, New Zealand's domestic net emissions will in fact only fall 17 percent by the end of the decade, compared to 2010. The Government's new Paris target is hardly more ambitious, with net emissions from all gases slated to be just 37 percent below 2010 levels by 2030.

The study Rogelj referenced relies on a handful of principles to determine each country's "fair share", including GDP per capita, emissions per capita and historical responsibility for emitting greenhouse gases.

There are other ways to look at New Zealand's burden. But by almost any metric, our domestic contribution falls far short. Our international effort, codified by our Paris target, rarely meets the mark either.

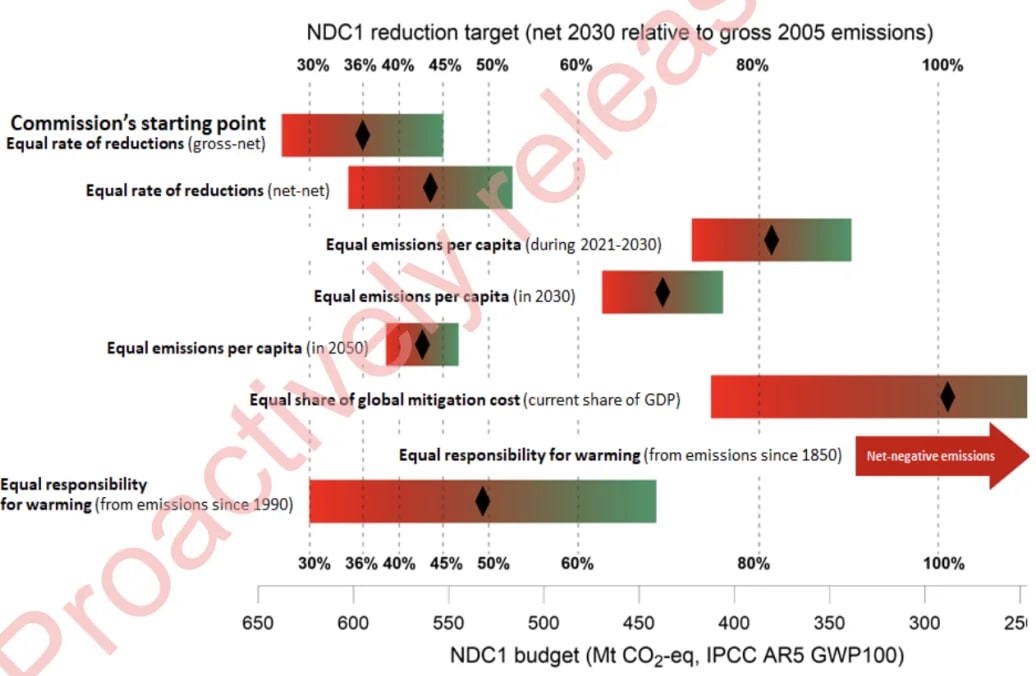

This is the conclusion of the Government's own work in the lead-up to setting the new Paris target. Officials from the Ministry for the Environment considered eight different equity principles that could be used to determine whether a given target represented our fair share.

The Paris target the Government chose in the end – in which net emissions in 2030 will be 50 percent below the gross emissions in 2005 – fell completely short of half of those principles.

Two of the equity principles the new Paris target does meet assume New Zealand only reduces emissions in line with the global average needed to limit warming to 1.5 degrees. New Zealand making only the same effort as is globally needed is hardly equitable, given its relative wealth, relatively high current emissions and historical emissions. Equal emissions based on population size would have required cuts of between 43 and 82 percent, depending on when you count populations.

If you take into account New Zealand's comparative wealth or its responsibility for warming since the industrial revolution, its fair share would probably require emissions to be net negative in 2030. It would have to be removing more greenhouse gases from the atmosphere than it emits.

This is why Climate Change Minister James Shaw wouldn't say New Zealand is doing its fair share when asked by Newsroom last year. Our Paris target is commensurate with the average effort needed worldwide but deeply inequitable when you consider the prosperity New Zealand earned from early industrialisation. That industrialisation came with costs to the environment, but we now have no intention of paying them.

Regardless of what the High Court decides on the climate lawyers' judicial review case, this debate on New Zealand's fair contribution won't be settled for years to come.