The term ‘noise’, in general use, can often have negative connotations, implying something unwanted or unpleasant. But as music makers we shouldn’t think of it as such.

Many musicians throughout the past century have explored the use of everyday noise as a credible musical instrument – from Luigi Russolo’s orchestral-industrial experiments in the 1910s, through to the ’40s musique concrete movement, and brought into the mainstream through the sonic experiments of Phil Spector, the Beach Boys and The Beatles in the ’50s and ’60s.

Noise is even an established genre in its own right. While music tagged with genres like noise, noise rock or drone is still thought of as experimental, it’s not hard to see elements of it creeping into the mainstream, particularly in cinematic soundtracks from the likes of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross or the prepared piano scores of Hauschka.

Whatever the context, ‘noise’ is a powerful and useful building block within sound design and music production, capable of adding tension, texture, character and movement to our tracks. And thanks to modern software techniques, noise has never been easier to access and experiment with.

What's that noise?

Before we get stuck into the hows and whys of using noise in music production, it’s worth taking a quick step back in order to define what, exactly, we’re talking about when we refer to ‘noise’. Obviously, all sound is technically noise, although generally we tend to differentiate between intentional sound, such as direct speech or music, and unwanted, unpleasant or incidental sound, which we refer to as noise.

Within music making, noise can have several different definitions. Synths often come equipped with a dedicated noise generator or an oscillator with a noise mode. Generally speaking, these tools are designed to create white noise. Standard synth oscillators operate at a certain frequency, with an audible pitch defined by the fundamental frequency, accompanied by varied combinations of overtones, depending on the waveshape.

By contrast, a white noise generator creates sound at an equal level right across the frequency spectrum. Just as white light contains all colours across the visual spectrum, leading us to perceive it as colourless, white noise is flat across the frequency spectrum so it has no definable pitch. Because of this, noise is a very useful sonic raw building block that we can chisel away at using filters and amplitude modulation.

There are a few slight variations to white noise. The most common you’re likely to encounter is pink noise, which decreases in level as it goes up the frequency spectrum, meaning that the higher frequencies are less harsh and lower ones seem amplified. Other variations include brown, violet and green noise, which are each weighted differently across the frequency spectrum.

Whereas noise in a synthesis context is generated intentionally, noise is also often an unwanted side effect of recording. All out-of-the-box audio gear has a ‘noise floor’ – a constant low level of electrical hum or hiss. This is often inaudible when hearing the gear in isolation, particularly in the case of more modern hardware, but can still be amplified by gain or compression and cause cumulative mix issues.

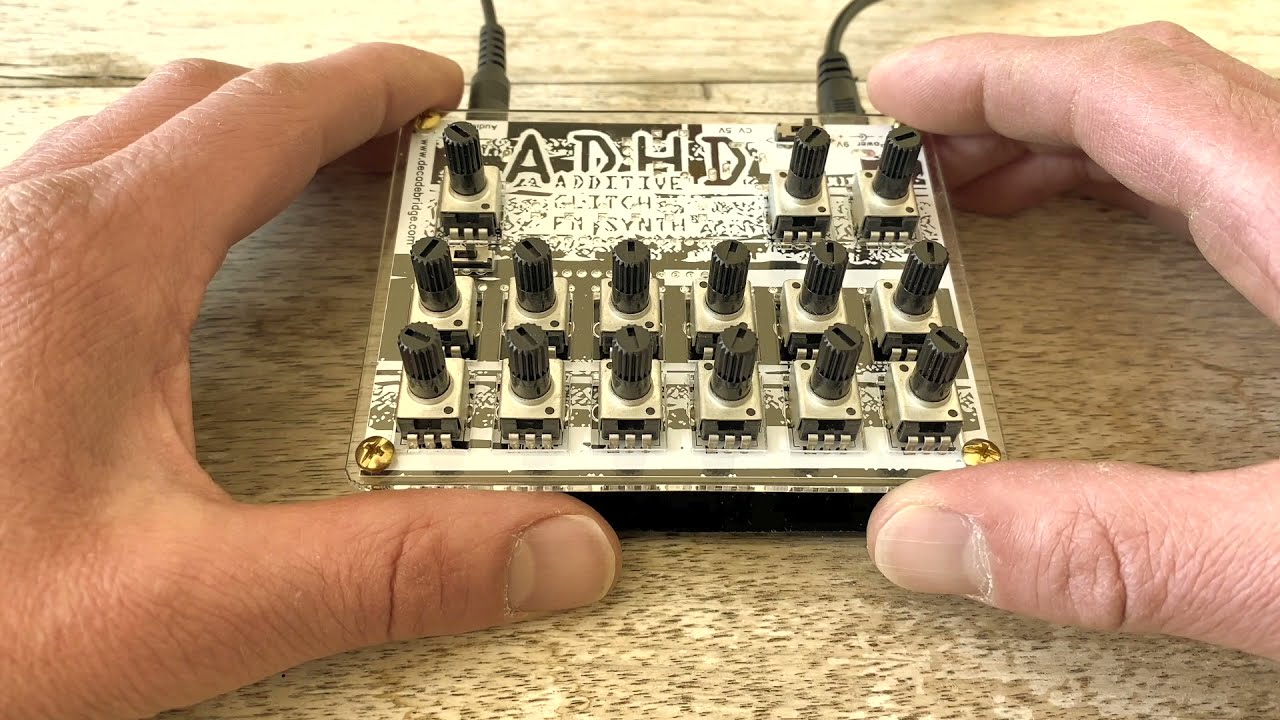

Noise can also manifest as additional sonic artefacts while recording or sampling, such as mic bleed or overspill, digital glitches or the mechanical noise of recording directly to tape.

Our definition of noise here also encompasses the incidental noises heard in the world around us, often recorded or sampled to musical effect. These could be overheard conversations, snatches of birdsong or rain, mechanical noise or a multitude of other sources.

So what do these different definitions of ‘noise’ have in common? It’s not true to say that all are unwanted, at least not in every context, and they’re not all unpleasant – few would argue with the notion that there’s something soothing about the noise of rain water or the crackle of a vinyl record.

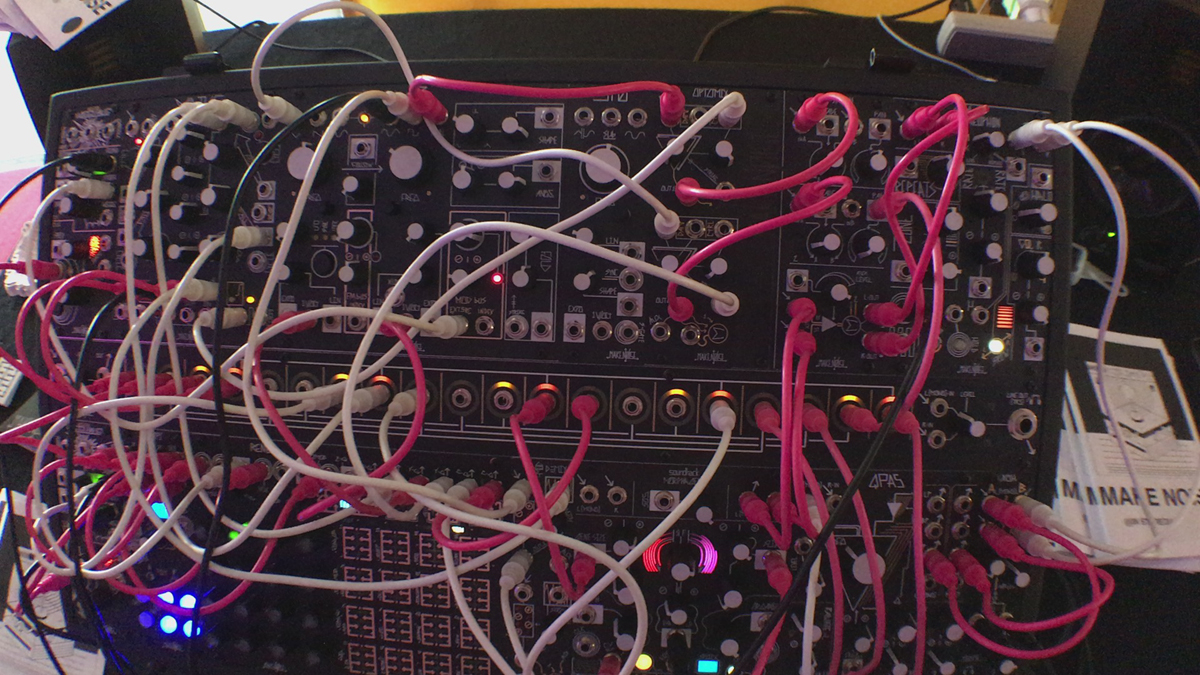

While most are unpitched – ie, lacking a recognisable fundamental frequency – that’s not true in all cases; natural sounds are often very musical, and the glitchy bleeps and resonances of a modular system can certainly stray into the category of ‘noise’ while still being recognisably tonal.

What links these different forms of noise – at least in terms of why they’re musically useful – is a level of unpredictability or randomness. Whether used to create texture, as a palette for sound design, or even as a modulation source, noise can offset the often rigid predictability of music making tools, whether that’s through offering inharmonic sound to embellish the tuned pitch of an instrument, or as an unpredictable texture set against the predictable rhythms of sequenced music.

Noise for texture and ambience

Modern music gear can be very precise and very clean. Particularly when working within the box, extraneous noise is rarely an issue, and pitch drift or inaccurate tuning only occurs when specifically emulated. As a result, music made entirely using software or contemporary digital gear can end up sounding sterile and lifeless for reasons that it’s difficult to put a finger on.

While some analogue purists might tell you this comes down to digital gear lacking character or ‘soul’, in reality it’s often the cumulative effect of lots of very accurate instruments and effects working exactly as they’re supposed to.

Our ears are used to hearing changes and variations in music, even when it’s subtle and almost imperceptible. This is why modulation and automation are such an important part of bringing a track to life. It’s also why, if every element is precisely tuned and programmed to sit exactly on the beat, the result is a monotonous sounding recording.

Layering noise into your tracks is an excellent way to counteract this. The inherently random nature of noise – be it generated white noise or an ambient recording – can go a long way towards adding an element of unpredictability to a composition, even when mixed in at a very low level. What’s more, the frequency-spanning nature of noise makes it perfect for filling gaps around other elements, helping to thicken up a mix.

Take, for example, the low-end rumble technique popular with big-room techno producers. While this is often achieved by applying reverb to a kick, to fill out the low end space with washed out lower frequencies, a similar effect can be achieved by pitching down and filtering any noise recording so that it fills out the sub frequencies, creating weight without creating a defined bass pitch. If attempting this, be sure to use compression or automation to duck your ‘rumble’ around the kick and other sub-heavy elements, or you risk creating an overloaded mass of low frequencies.

Layering noise recordings within a track to create texture and ambience has long been a tried-and-tested technique within electronic music. A common approach is to layer recordings of vinyl crackle or tape noise into digital productions, in order to replicate an element of the lo-fi character that would come from analogue gear or vinyl sampling.

In all honesty, as effective as it can be, this technique of faking a ‘vintage’ sound feels a bit overused in 2024, and arguably a little dishonest – but there are plenty of ways that we can apply a similar idea in a manner that is more unique and creative.

For one, try doing the opposite of what standard recording advice suggests, and boost the noise inherent in your recordings. Take any external recording source – be it a hardware instrument, external effect loop or mic source – and boost and compress the input until any electrical or background noise becomes a prominent part of the recording.

Ambient recordings from the world around us make a fantastic source of layered texture

Alternatively, ambient recordings from the world around us make a fantastic source of layered texture. Monolake’s dub techno classic Hong Kong is a brilliant example of this, in which recordings captured in the titular city are layered over electronic beats to create an all-round more natural-sounding take on dance music. Burial’s music is another prime example of this in action.

In both these cases, the ambient recordings are brought to the forefront of the mix, at times providing rhythm and character as much as ambience. Even at almost inaudible levels, however, mixing ambient recordings into an electronic track can go a long way to giving the mix a realistic sense of ‘place’.

A more recent example of a producer known for these kinds of techniques is Fred Again.. whose tracks often feature short looped recordings. These might be overheard chatter, street noise or general ambience, but are usually looped in order to create a rhythmic hook as much as a sense of ambience.

Rhythmic Ambience with Cableguys Shaperbox

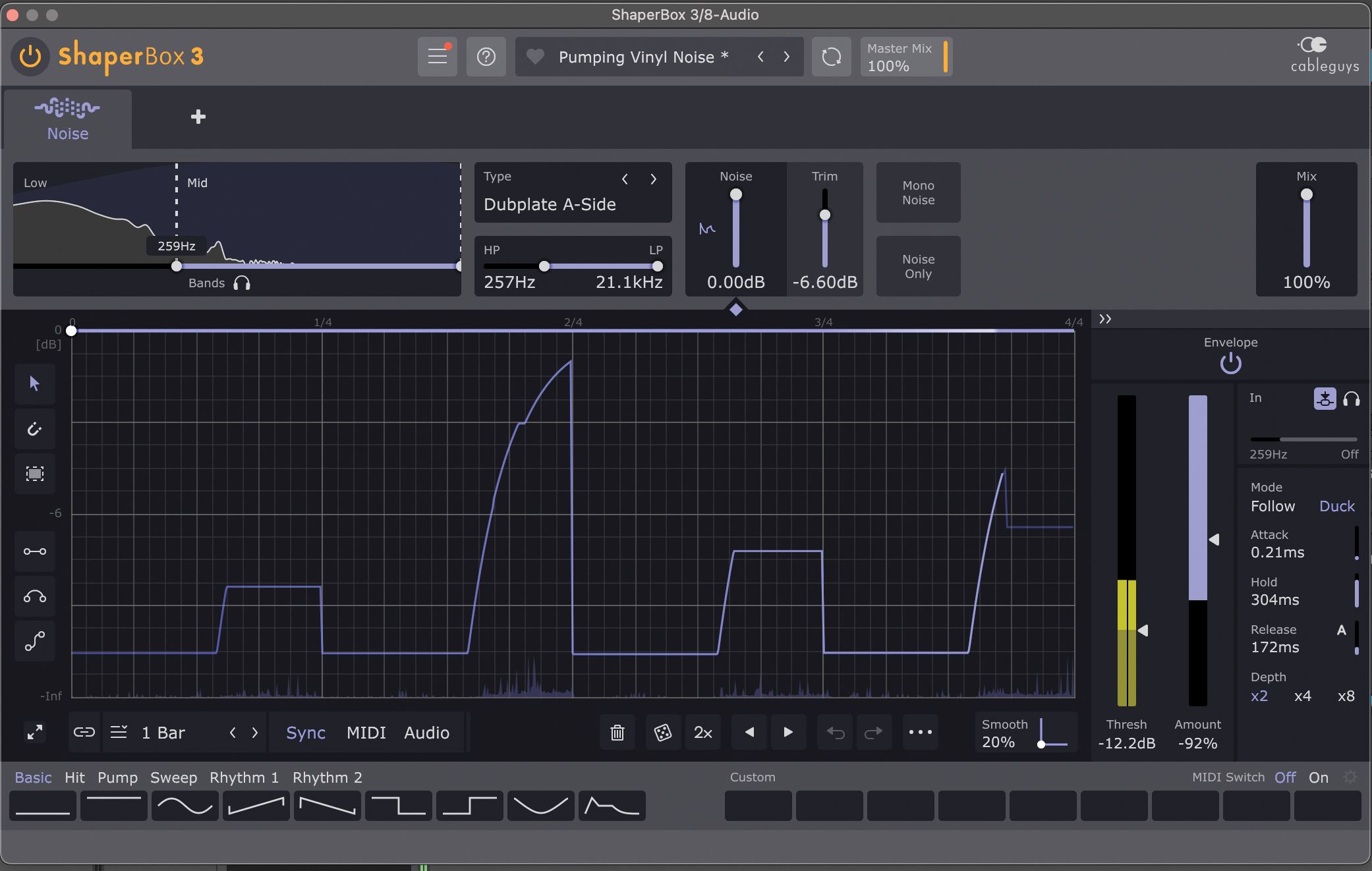

Part of Cableguys ShaperBox, this modulation-centric effect is a must-have for noise fans.

As we explore opposite, there are plenty of ways to process noise recordings using just the basic tools within your DAW. For a specialised tool, however, NoiseShaper – part of Cableguys’ ShaperBox package – is hard to beat. One bonus of NoiseShaper is it comes stocked with a broad variety of noise generator types, ranging from white noise through to vinyl or tape crackle, natural sounds and household objects.

It’s worth being aware that ShaperBox functions as an effect processor, so generally requires an audio input to process. By disengaging NoiseShaper’s envelope triggering and using ‘noise only’, we can use it to generate sound without the need for an input though.

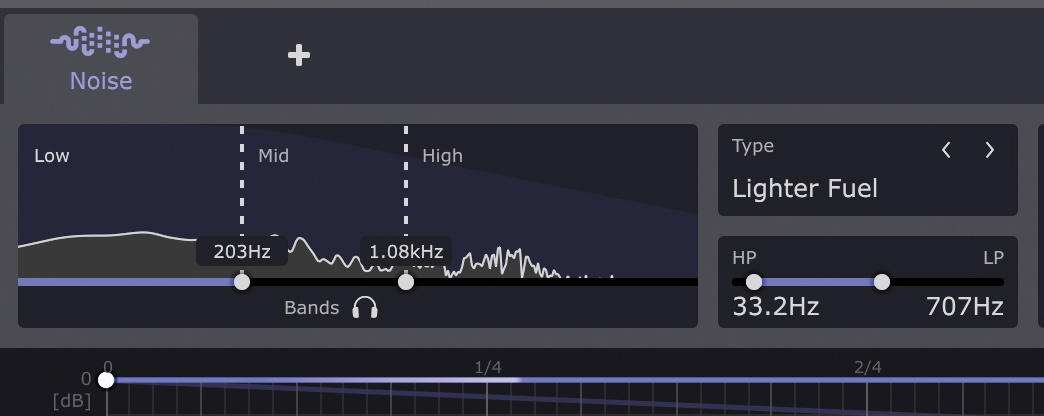

Multiband noise

ShaperBox functions across three adjustable frequency bands, and NoiseShaper can filter the noise within each of these further, meaning we can, for example, create a low rumble and top-end hiss simultaneously.

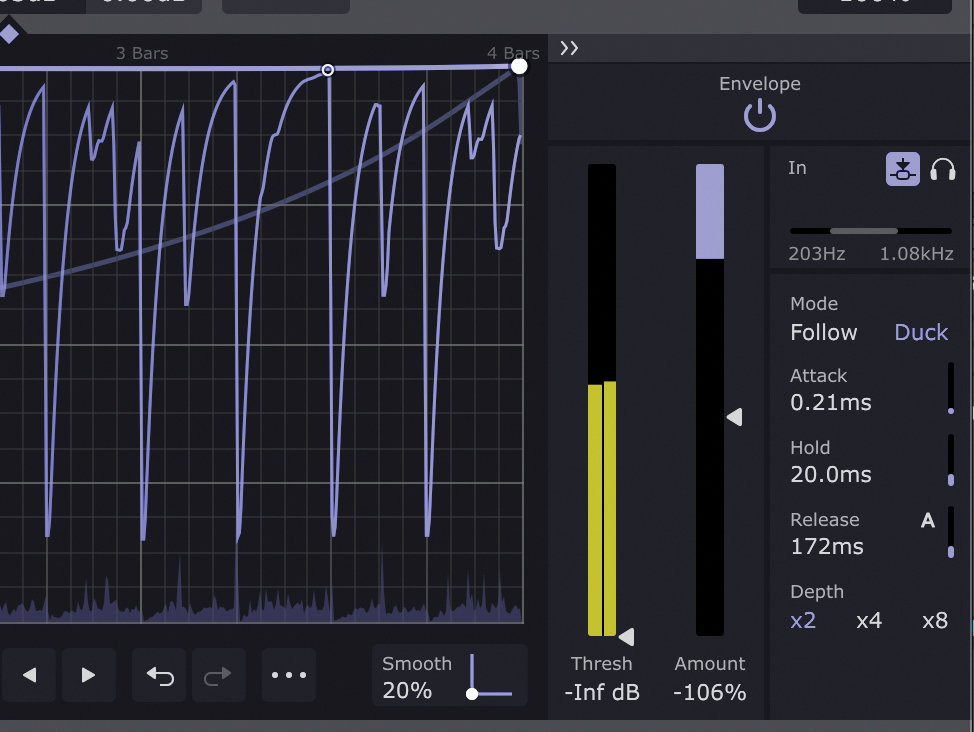

Envelope triggering

By sending a sidechain input to trigger NoiseShaper’s envelopes, we can tailor each frequency band to respond to a kick or drum loop, either ducking out of its way or pumping in time.

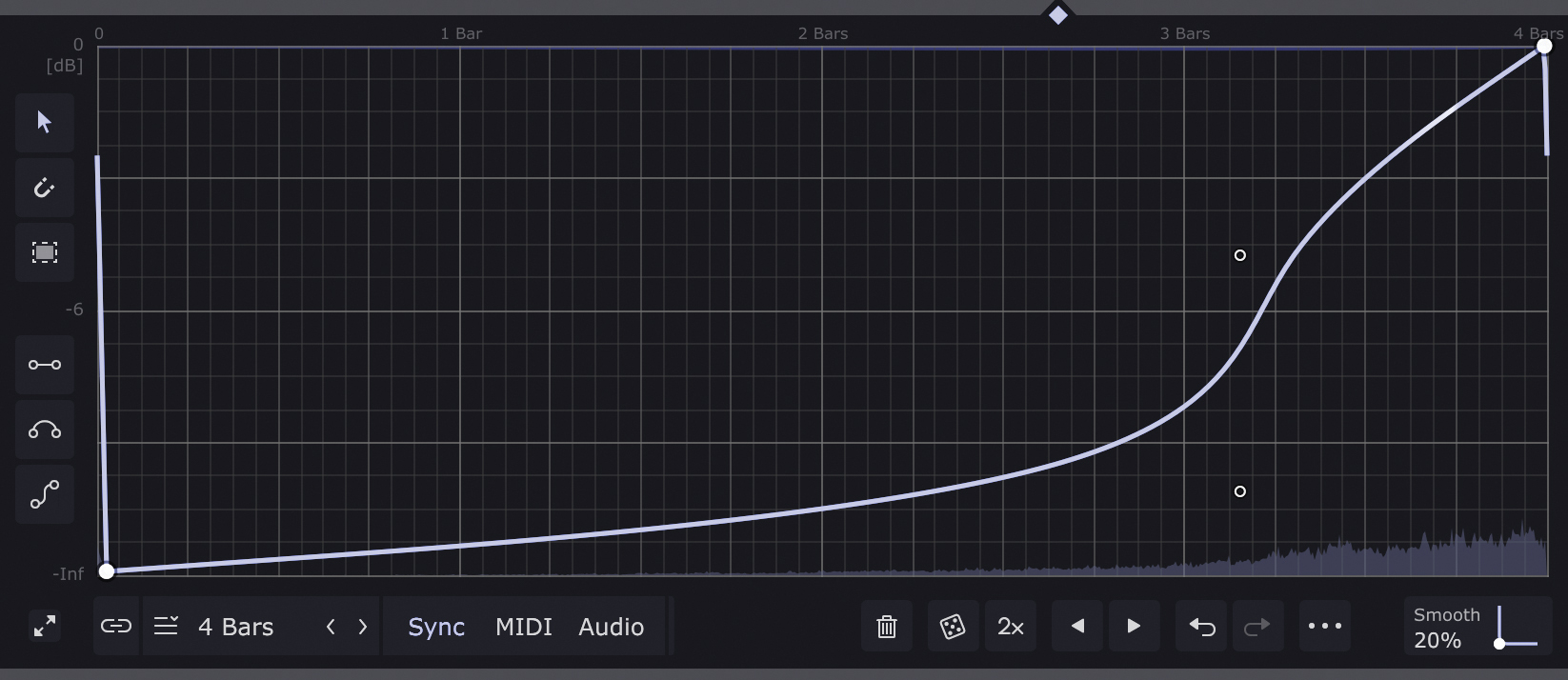

Shaped sweeps

ShaperBox’s distinctive curve shapers can modulate most parameters in NoiseShaper. Applying a slow build or fall to the noise’s level or filtering is a quick and easy route to classic FX.

Noise and percussion

Noise’s atonal nature makes it the ideal starting point for electronic beat-building. The synthesised drum sounds created by Kraftwerk paved the way for popular drum synthesis techniques and commercial drum machine technology, a lot of which utilises noise as a source for sculpting hi-hat, clap and percussion sounds. Electronic cymbals and hats are reasonably straightforward to synthesise: by shaping a noise oscillator’s amplitude via the synth’s envelope, then applying a modulated filter, you can replicate the characteristics of basic closed and open hi-hats, as well as longer cymbals and rides.

More complex, real-world drum sounds will often be made up of several elements: imagine a kick’s initial transient punch or click, a tuned body/tail, then any extra subtle ambience captured from the initial recording environment. Noise is an ideal tool when replicating these elements through synthesis and layering techniques – whether to synthesise the initial transient click of a kick, or the top-end ‘splash’ of a snare. Layering noise also allows you to mix in extra ‘fizz’ behind a dull drum sample or recording, adding power and thickness in a mix.

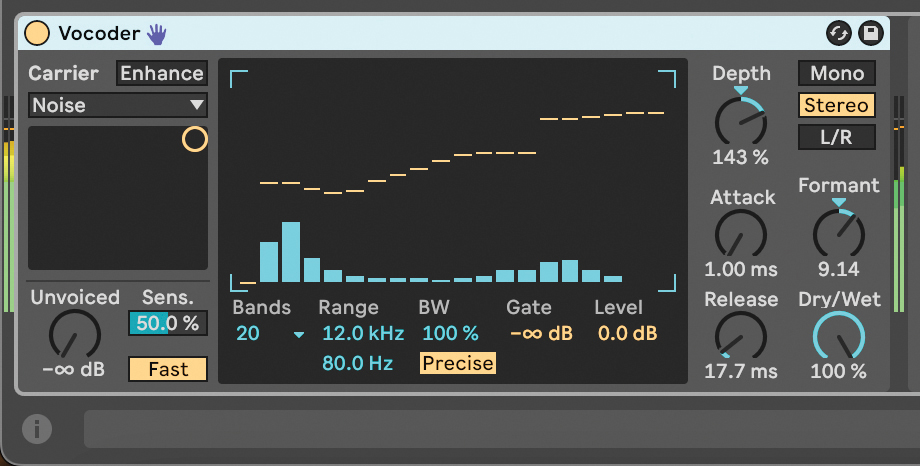

Many vocoders feature a noise generator that can be used as a carrier signal

One often overlooked tool for noise layering is the vocoder. Vocoders use one signal to modulate another, most commonly using a human voice to modulate a synth tone. Many vocoders feature a noise generator that can be used as a carrier signal (ie, replacing the synth in the above example). Try using this, and route a drum pattern as the modulation source. This is great for creating fizzing, splashy percussive sounds. Process the output with a little reverb and layer it with the dry drum loop as a way to add character and extend the tail of your drums.

A similarly handy tool for blending percussion and noise is convolution reverb. Try loading a recording of noise in as an impulse response for your favourite convolution tool, and then use it to process a drum pattern. Using simple white noise can create splashy reverb tails, but when used with more distinctive noise sources, such as rhythmic crackles, mechanical sounds or natural recordings, this can be a powerful creative tool, imparting some of both the character and rhythm of your noise sample onto the drums.

Separating noise from other elements

In recent years we’ve seen a rise in software tools that let us separate noise – ie unpitched elements of a sound – from tonal elements. RipX, from Hit’n’Mix, is one such application. This uses machine learning in order to separate the two elements of a source sound. This has obvious uses for mixing and post production, making it easy to remove unwanted noise from a poor quality recording, say. But it can also be used creatively, for example by boosting noise elements in a sound to unnatural levels in order to bring out unique character.

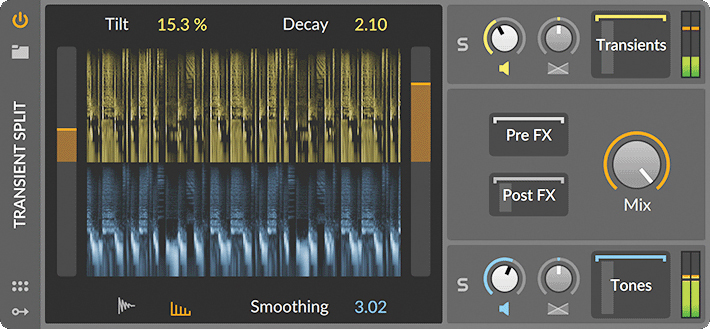

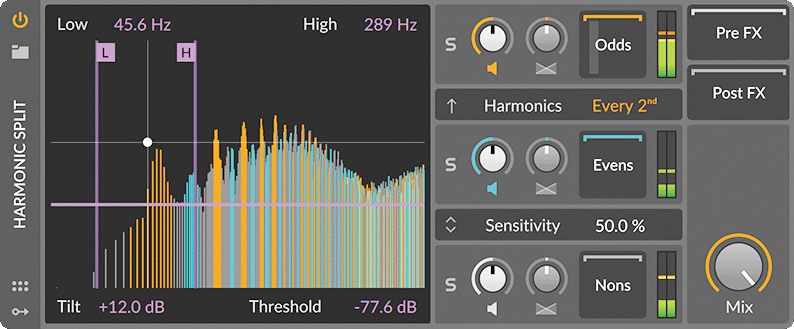

Possibly our favourite tools in this realm are Bitwig Studio’s suite of Spectral Effects. Unlike tools like RipX, which generally work offline – ie they analyse and then separately output the pitched and unpitched elements – Bitwig’s spectral tools are splitters that allow for ‘live’ processing of different elements of an audio feed. These tools can split sound in various ways, including separating different frequency bands and loud versus quiet elements. When it comes to working with noise, however, there are two Spectral Effect devices of note.

The first of these is the Transient Split device, which allows users to separately process the percussive transients and tonal body of a sound. Broadly speaking, when it comes to drums and percussion, it’s the transient elements that tend to be more noise-like, while the body – particularly in the case of kicks and snares – often has a more defined pitch.

As well as adjusting the balance of these elements, the Spectral Effect devices allow for individual effect chains to be applied to each. There’s no end of ways to be creative with this, but one particularly appealing technique is to apply creative reverb or delay just to the noise-based transient elements of a sound.

Similar in scope is Bitwig’s Harmonic Split device. This divides an incoming signal into odd and even harmonic feeds, but also has a third output for non-harmonic sounds. This can be fun for isolating the noise elements and extracting them from a more complex loop – a low-quality vinyl sample, for example – or distorting just the non-harmonic noise elements of a sound.

How to...

Create a classic FX sweep

The ‘noise sweep’ is a bread-and-butter synthesis technique. Take a raw white noise signal, apply a resonant low-pass filter, then open and close the cutoff and resonance to create wind-like rises, whooshes, bursts and impact FX that can be used to transition between, emphasise or intensify sections of a track. You can do it using a synth, or by using a white noise sample and a filter plugin.

Generally speaking, noise FX like these work well when used to fill out the stereo field, so generously apply widening, auto-pan, delay, reverb and modulation effects. Increase or decrease an auto-panner’s speed and intensity to ramp up excitement before a drop, and slather a sweep in reverb and delay to soften its effect, sinking it into the track. Rhythmically, you can always get things moving with trance gating and sidechain pumping.

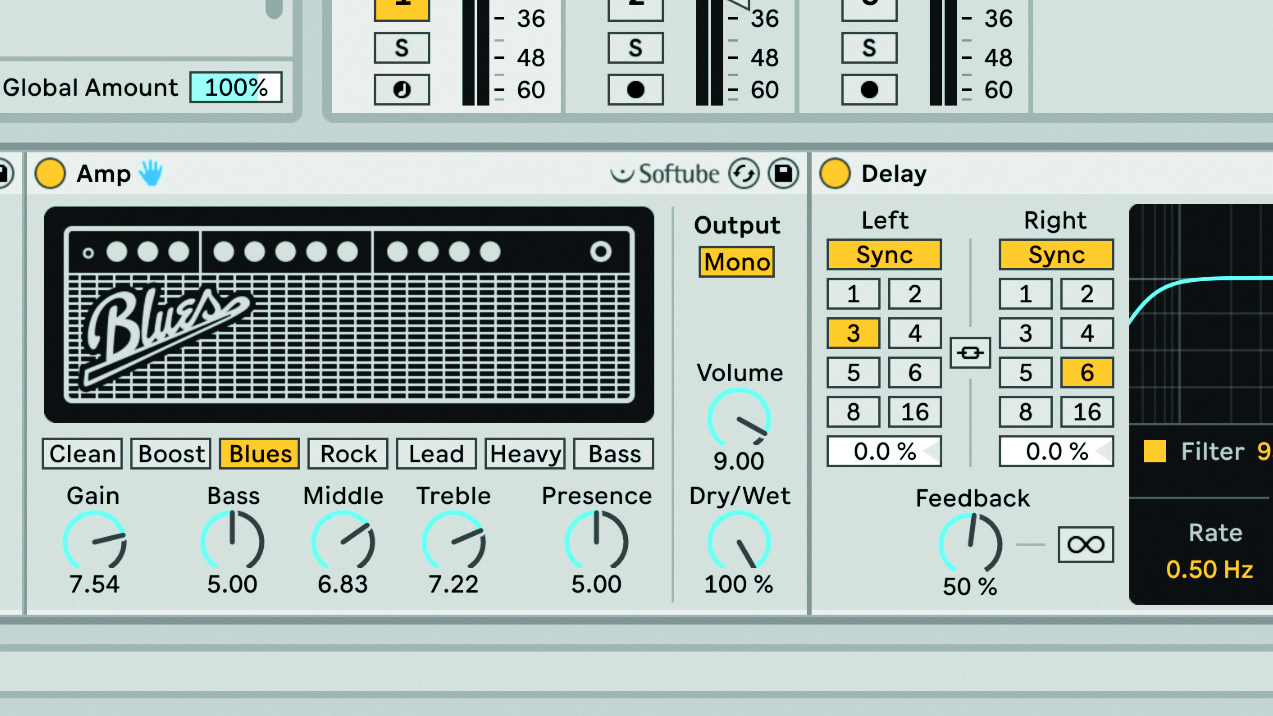

Use noise in a synth patch

Many synths have a noise generator, but why use one? Aside from the percussive uses already discussed, dialling in a little noise can add air and punch to your synth patches. This works particularly well coupled with a modulated low-pass filter. With a lower cutoff, any noise in your patch will likely be inaudible. As the cutoff opens, however, the addition of noise will bring thickness and texture to the sound. With a short filter envelope, this is a great way to add percussive ‘punch’ to a patch.

Mix with pink noise

Some mix engineers swear by using pink noise as a reference point for mixing. It works like this: instead of pulling up a reference track or part of your own mix to set your levels against, use a noise generator outputting pink noise. Set this output so that it’s hitting a sensible level on the master output.

Now solo each track or bus in your mix in turn, and set it so it’s just audible over the pink noise. Do this for each track individually, and you should have a good starting point mix for your track, whereby all your channels are roughly balanced with plenty of headroom left. A decent state to mix from.

Use noise as a tonal source

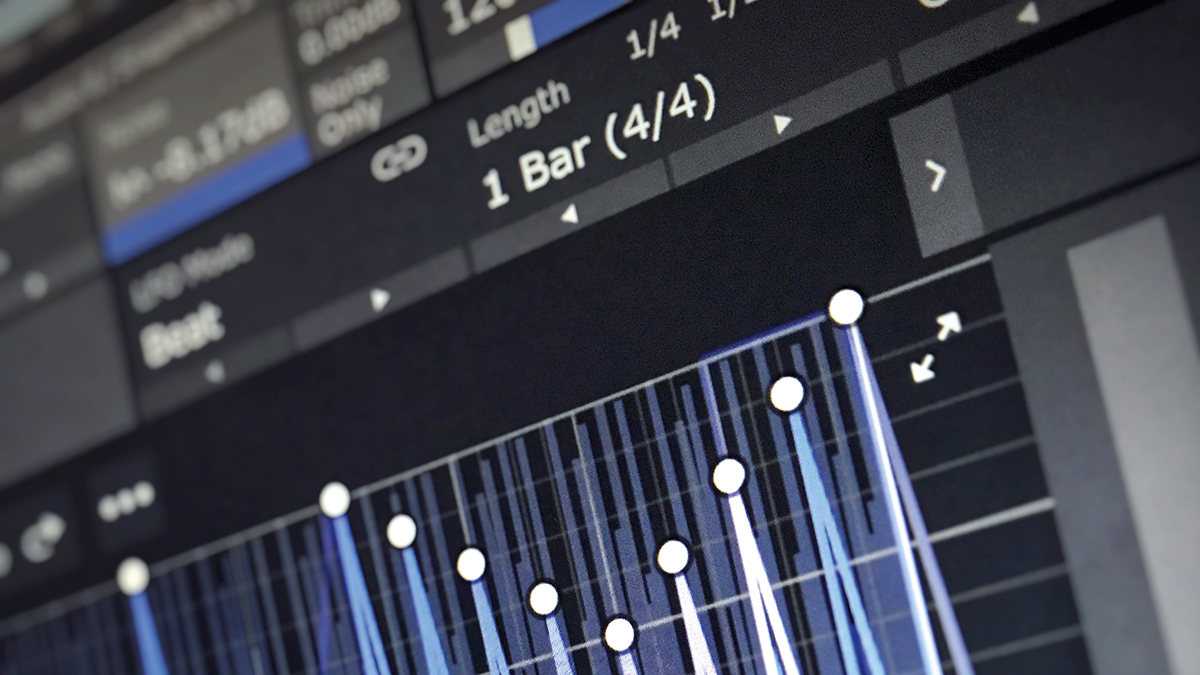

White noise is inharmonic and atonal in nature, but filtering can be used to isolate frequencies of a discernible melodic pitch. This kind of noise filtering is ideal for creating experimental bleeps and unexpected musical patterns – filter keytracking in a synth can help here. Try modulating a resonant band-pass filter’s cutoff with a square LFO to create stepped sequences at various pitches. Try recording these filter sweeps and sequences and then resample them using your DAW’s sampler; now modulate the pitch of the sample playback for even more weird tonal and rhythmic effects.

Aside from the percussive uses already discussed, dialling in a little noise can add air and punch to your synth patches

Use noise as a mod source

As well as the actual sound, we can use noise for modulation purposes. In fact, many synths allow a noise oscillator’s frequency to modulate other parameters – said noise is often filtered first, to remove high frequencies that might cause the modulation to be too fast (though this can be cool in itself!).

A classic way of achieving an unusual wandering vibrato is to apply a low-pass filter to white noise and then use this low-frequency energy instead of a sine wave to modulate a target such as filter cutoff or pitch. Remember that the result won’t be exactly the same every time when you do this.