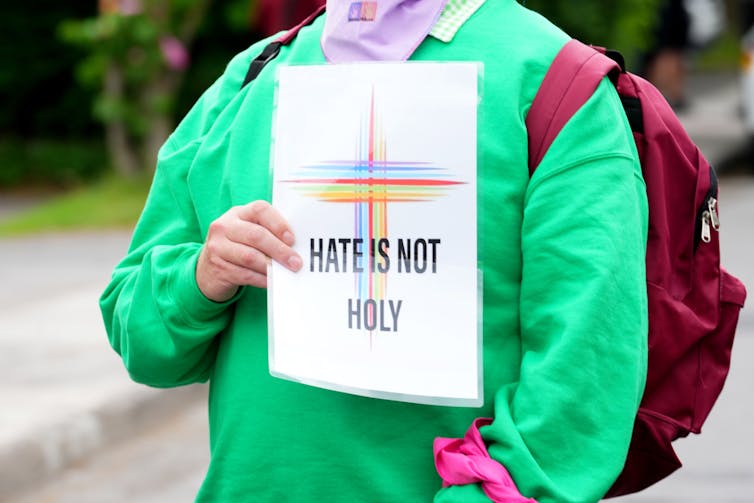

Each summer, Pride is celebrated across the world in support of LGBTQ+ inclusion, diversity and human rights. Given the recent backlash against LGBTQ+ communities in Canada and elsewhere, Pride is more important than ever to promote visibility and challenge discrimination.

In recent months, some Muslim communities in Canada and the United States have protested against LGBTQ+ inclusion. Socially conservative Muslims have criticized what they see as growing LGBTQ+ “indoctrination” in schools and society more broadly.

In Michigan, a Muslim majority city council banned Pride flags from being flown on city property. In Ottawa, young children at an anti-LGBTQ+ protest stomped on Pride flags.

Similar protests also took place in Calgary and Edmonton, where one teacher was surreptitiously recorded lecturing Muslim students about skipping school as part of a national protest movement against Pride month activities. The National Council of Canadian Muslims cited the teacher’s comments as Islamophobic.

Pride and protest

This year the Christian anti-abortion group Campaign Life Coalition, organized a National Pride Flag Walk-Out Day on June 1 designed to target Pride month celebrations in public schools. The walk-out protests were also supported by a series of “pray-ins” held at Catholic school boards and dioceses across Canada.

Given their vast financial resources and faith networks, Christian evangelicals have redoubled their efforts targeting LGBTQ+ communities, which have been buoyed by recent political lobbying successes in Uganda, which saw the government pass some of the harshest anti-LGBTQ+ laws in the world.

In Canada, conservative religious groups are also trying to take over school boards by having candidates run in elections under the guise of “parent voice” and anti-LGBTQ+ platforms.

Much of this rhetoric is couched within language about parental rights and protecting kids, which is inherently premised on the belief that teaching about LGBTQ+ identities is wrong.

These tactics are not new but harken back to the days of gay rights opponents like Anita Bryant. Her 1970s “Save Our Children” campaign sought to roll back anti-discrimination laws and prohibit gay and lesbian people from teaching in schools or working in public services.

These campaigns branded gay and lesbian communities as pedophiles who posed a direct threat to the moral fabric of society and helped launch the careers of noted homophobic televangelists such as Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, Jimmy Swaggart and others.

Today’s right-wing talk show pundits and politicians use similar language and tropes that link LGBTQ+ identities with odious terms like “groomer.” What’s old is new again, but with a twist in logic and strange new alliances.

Building new coalitions

Seeking to build new coalitions of support, far-right evangelicals have been courting conservative Muslims to jump on their homophobic bandwagon against LGBTQ+ rights and inclusion.

Sadly, some conservative Muslim leaders are now fanning the flames of hatred against sexual and gender minorities. For example, some conservative imams and Muslim think tanks have latched onto similar narratives about the moral decay of Western societies and the dangers of Pride movements. They warn against allying with the “progressive left” and against supporting LGBTQ+ equality.

Muslim accommodation of gender diversity

Muslim societies have historically accepted gender diversity. Even today, despite societal discrimination, there exists a variety of diverse gender identities like the hijras of South Asia and the khanith of the Middle East.

In South Asia, multiple gender identities such as the zenana, chava, kothi and so on exist. On the Sulawesi Island of Indonesia there is also recognition of multiple gender traditions.

There is also Islamic scholarship on the accommodation of gender and sexual minorities in Islam. This includes work by one of us (Junaid B. Jahangir) on the issue of Muslim same-sex relationships. This research offers an invitation to traditionally trained Muslim scholars to revisit the issue with a renewed perspective.

Moreover, this scholarly work builds on the seminal contributions of researchers like Islamic studies scholar Scott Kugle and writer Samar Habib.

In addition, gender identities are well recognized in Islamic jurisprudence. The mukhannathūn (effeminate men) of Medina inhabited the social space during the time of the Prophet. Muslim jurists derived laws of inheritance, funeral and prayer for the khuntha mushkil (indeterminate gender) individuals.

Traditional Islamic texts offered such individuals prayer space between the rows of men and women. The Encyclopedia of Islamic Jurisprudence documents rulings on the marriage of such persons.

In 2016, a group of clerics in Pakistan issued religious edicts permitting third-gender individuals to marry.

There have also been edicts permitting gender reassignment surgery issued from the highest bodies of both Sunni and Shia Islam.

However, allowance of gender reassignment surgery does not automatically translate into acceptance. For instance, while Iran is deemed as “the global leader for sex change,” it remains heavily opposed to LGBTQ+ rights.

Avoiding the anti-LGBTQ+ bandwagon

Nonetheless, when Muslim groups in Western democracies jump on the anti-LGBTQ+ bandwagon, they act against the longstanding accommodation of sexual and gender diversity in their own tradition.

Our main worry is for LGBTQ+ Muslim youth who may be isolated without support from their families and communities. Thankfully, there are Muslim community groups providing important sexual health education which embraces Islamic laws and traditions.

This community education is especially important when youth struggle with their sexuality and gender in an environment where they cannot be open about their identities. Muslim leaders like the late Maher Hathout acknowledged and offered a compassionate view on Muslims struggling to reconcile sexual and religious identities.

Islamic teachings on sexual and gender diversity are far more diverse than what many conservative groups would like us to believe. Discrimination based on religious dogma undermines and threatens the individual freedoms essential to secular and democratic societies. Building more inclusive societies means we must all challenge prejudice and hate from both within and outside our communities.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.