If you have ever seen a shooting star on a clear night, surely someone has invited you to make a wish. Nevertheless, this is a natural phenomenon without any magical connotation – beyond its great beauty, of course.

What is a shooting star, really? Where do these glowing, moving bodies come from? How and when can we observe this astronomical phenomenon?

Meteor shower or shooting stars?

Although we popularly call them shooting stars, they are not really stars but glowing dust particles. To understand why, it is a good idea to first distinguish between a meteoroid, meteor, and meteorite.

The word meteor refers to the astronomical phenomenon that occurs when one or more particles of matter (meteoroids) enter the atmosphere at high speed. These meteoroids, which are usually very small (between a tenth of a millimetre and a few centimetres in size), are fragments of dust, ice, or rock that wander through space.

Due to the effect of our planet’s gravity, if their trajectory is close enough, they become attracted to the Earth and rush towards it, colliding at high speed with the air molecules in the atmosphere. Due to friction, they reach extremely high temperatures and begin to smoulder, producing a bright, luminous trajectory on their descent that makes them resemble stars.

The duration of this phenomenon is usually very short (fractions of a second, hence the term “shooting”) and it will depend on the size, speed, and composition of the particles.

Meteors begin to emit light at about 100 kilometres above the Earth’s surface. Normally, they stop being seen when they have fully burnt out (when they reach about 60–70 km in height).

Therefore, since they are not really stars, it would be more appropriate –although less romantic– to call them meteor showers instead of shooting stars.

Sometimes, with a lot of luck, we can see huge, bright meteors. They look like balls of fire and leave a trail of light that lasts for several seconds, even minutes, simultaneously producing sounds and explosions. These meteors are called bolides.

If the meteoroids (the particles that enter the atmosphere) are large in size (initial mass greater than 1 kg) they may not fully disintegrate. If a fragment reaches the surface of our planet, that would be a meteorite (a stone that falls from space). There are many collections that feature recovered meteorites, and the study thereof allows us to discover the composition of celestial bodies beyond our Earth.

What is the origin of meteor showers?

Where do the particles from outer space that produce meteors come from? Some of these particles have existed since the formation of the solar system, but most are produced during the journey of certain comets around the Sun.

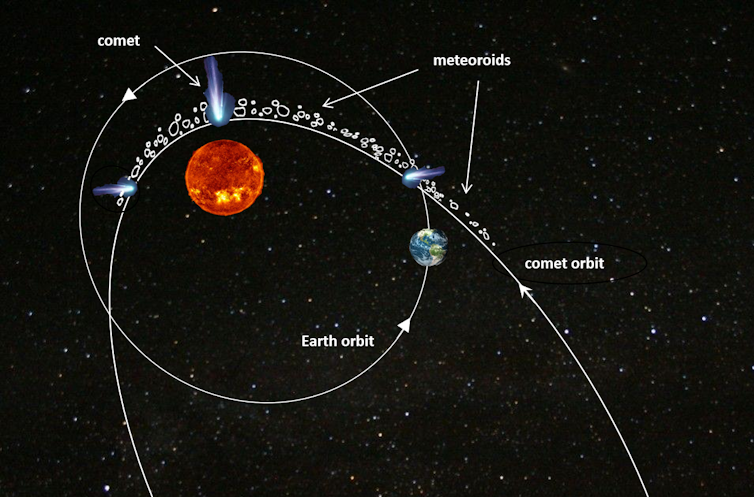

As they orbit the Sun, comets (huge bodies of ice and rock) release a series of gases, dust, and rocky materials into space due to the effects of heat and the solar wind. These released materials remain in an orbit very similar to that of the comet itself. Thus, each comet forms a kind of ring with the fragments that it releases after each step as it moves.

If the Earth, in its orbit around the Sun, intersects one of these rings, some of these rocky fragments released by the comet are caught by the Earth’s gravitational field and fall at great speed through the atmosphere, forming a meteor shower.

When can we see meteor showers?

If, while on vacation, we are in a place far from the light pollution of big cities, we should take advantage to go out for a relaxed stroll at night. If we look up, we will be amazed by the sight of stars, planets and the Milky Way. And, maybe, we will also be lucky enough to see a shooting star.

But shooting stars are not only visible in summer. In fact, 14 meteor showers take place throughout the year every year, ten of which can be seen at night. Each one is associated with the passage of a comet that has left a trail of meteoroids on its way.

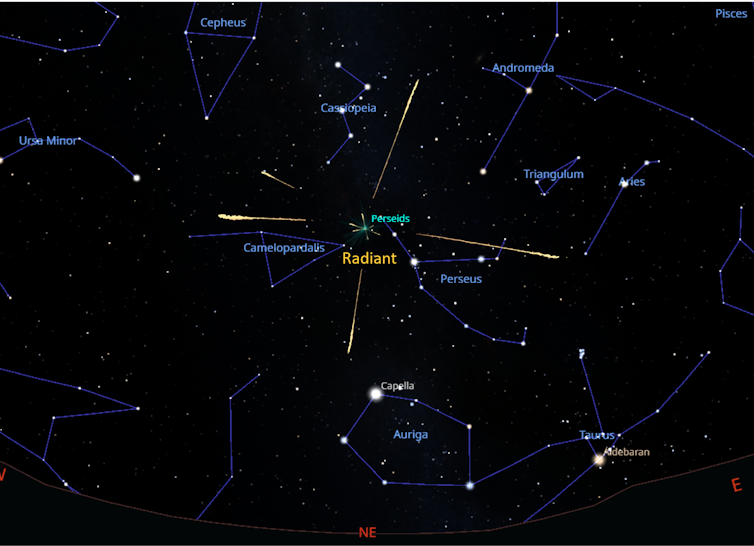

The most popular meteor showers are possibly the Perseids, which are also called the “Tears of Saint Lawrence” because their maximum activity (in mid-August) is close to the date of said Saint’s martyrdom. The parent comet of the Perseids is the comet Swift-Tuttle. The maximum meteor shower rate usually occurs on August 13 (it can vary), with an average fall of about 100 meteors per hour.

But both the Quadrantids (visible in January), with a rate of 120 meteors per hour, and the Geminids (in December), also with a rate of about 120 per hour, are just as spectacular.

This meteor shower rate is what would be observed with the naked eye in a place where the radiant is directly overhead (at the zenith) and visibility conditions are optimal. So, if we go out to observe a meteor shower, we must be moderate with our expectations and not be disappointed if we see less than we thought.

It is important to understand the concept of the meteor shower’s radiant because this is the point in the sky from which shooting stars appear to emerge at the time of maximum occurrence. This point can be precisely defined in the form of astronomical coordinates, but it can also be defined as the region of the sky in which the constellation that gives the meteor shower its name is located. Like Perseus for the Perseids, or Gemini for the Geminids.

Observation tips

Look for areas with little light pollution (therefore, and unfortunately, far from cities) from which the longest possible section of the horizon can be seen.

Be very patient: shooting stars do not appear constantly or just as soon as we start our observation.

If possible, go out to stargaze on nights when there is no moon or when the moon is close to a new moon.

Know how to locate the reference constellation so that you can find the radiant (the area from which the meteors seem to emerge).

Lie down comfortably looking up at the sky.

Look with the naked eye. To observe this phenomenon, you need to observe a wide region of the celestial vault, so it is not necessary (or recommended) to use binoculars.

Even if it is summer, take warm clothes and supplies to be able to gaze comfortably for the required amount of time.

And remember, even if you do not manage to see a meteor, you will still enjoy the wonderful experience of observing the heavens.

M. Julia Suso López does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.